Nancy Oda was very happily retired when she learned about Tuna Canyon.

“Very happily retired,” she says for a second time. “It was like a call to action.”

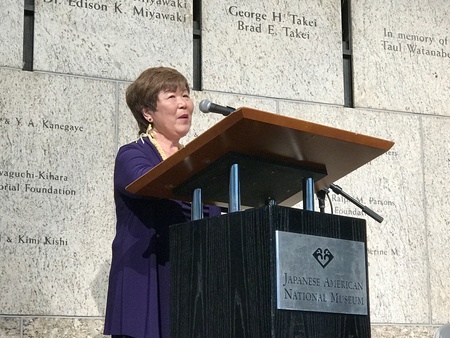

We’re sitting together in the small back room of the Hirasaki National Resource Center at the Japanese American National Museum, just past Only the Oaks Remain: The Story of Tuna Canyon Detention Station, the special display that Oda helped to develop. Four years ago, she may not have heard of the historic site, but it’s since become a central part of her life.

“I’m really happy when I go to social events and people say, ‘Oh, how’s your preservation project coming along?’,” she says.

“I have all my pamphlets, I’m ready to go. But I know that there’s a time and a place and you need to be respectful of what’s happening. Because I could jump up on my little soapbox and bring everybody along.”

Oda speaks with a calm but impassioned voice, the same one I imagine she used in her years as an elementary school teacher and principal. Teaching runs in her family, as does a deep sense of history. Her grandmother was a teacher, then principal in Japan, and her father, a kibei, taught judo, both before and after the war.

“A lot of people dread coming to the principal’s office,” she says. “But I don’t think people dreaded coming to my office. We were gonna have quality time. And I would have toys there because there’s only so many lectures you can give a five-year-old… I see that leadership has to be grown from a very early age. If you beat them down, they don’t grow, they just get repressed… I want them to be able to speak from their hearts.”

Oda now uses this same philosophy (minus the toys) as president of the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition. As the coalition members work together to develop Only the Oaks Remain—and it is a work in progress, scheduled for travel after JANM to the Manzanar Historic Site and California State University, Fullerton—she makes sure the display includes all their diverse perspectives without becoming too wordy. Each panel represents hours of conversation, by phone and email—and over unagi donburi and chirashi at Mitsuru Grill.

“I keep the coalition together,” she says. “My goal is to keep everyone’s voice heard…I’m just a conduit.”

Tuna Canyon came into Oda’s life four years ago. By then, she was three years into retirement and volunteering as president of the San Fernando Valley Japanese American Community Center (SFVJCC) when Los Angeles City Councilmember Richard Alarcon approached her organization about his proposal to give Historic Cultural Monument status to the Tuna Canyon Detention Station.

Born in the Tule Lake concentration camp, Oda knew the history of Japanese Americans during World War II better than most, so she was surprised that she had never heard of Tuna Canyon, a wartime prison camp located less than 20 miles from the Boyle Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles where she grew up. That night, she went home and looked it up on Densho Encyclopedia.

“I’d never seen it or heard of it,” she says. “But I’m a child of the camps, so I have a very deep reason for supporting something like this.”

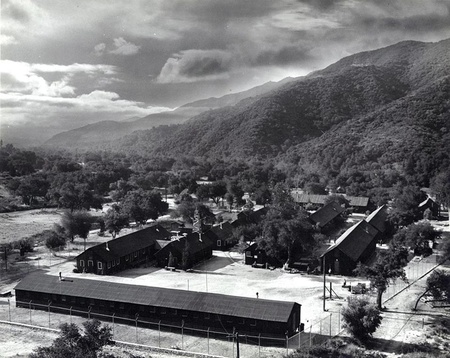

That night on Densho, Oda learned that while she and her family were incarcerated at the Poston and Tule Lake concentration camps, Tuna Canyon temporarily held over 2,000 Japanese, German, and Italian immigrants, as well as Japanese Peruvians, before sending them off to the concentration camps where they would spend the rest of the war.

Oda had never heard of Tuna Canyon because by the time the war ended and her family returned to Southern California, the detention station had been converted into a reform school for boys. By 1960, it was a golf course, its wartime history rendered invisible.

Alarcon had reached out to the SFVJCC hoping that one of its officers would appear at City Hall to support making Tuna Canyon a Historic Cultural Monument. The motion passed unanimously in June of 2013, but later that year, the landowners, Snowball West Investments, sued the City of Los Angeles to have it repealed. By then, Oda was all in.

She helped to form the Tuna Canyon Detention Station Coalition with the goal of building a permanent monument at the Tuna Canyon site. The traveling display, Only the Oaks Remain, was the next best thing. Eventually, the group hopes to install a permanent education center beneath the oaks of Tuna Canyon.

Meanwhile, Oda is also working on another, more personal project. Since 1973, she has been translating her father’s wartime diaries. A No-No Boy, he journaled about his life at Tule Lake.

“I am writing this because I cannot battle with a rifle at this age,” he wrote, then 33 years old. “This diary is for my country, the United States of America.” Remembering his experiences keeps his daughter inspired and strong as she fights to preserve Tuna Canyon’s history.

“My father had to rebuild his life after the war. and he didn’t speak English,” she says. “So this is way easier, don’t you think?”

* * * * *

*The Only the Oaks Remain: The Story of Tuna Canyon Detention Station display at the Japanese American National Museum has been extended for viewing through April 16, 2017.

© 2017 Mia Nakaji Monnier