During World War II, sugar was in urgent demand. Beyond its use in food products, sugar beets were converted to industrial alcohol and used in the manufacturing of munitions and synthetic rubber.

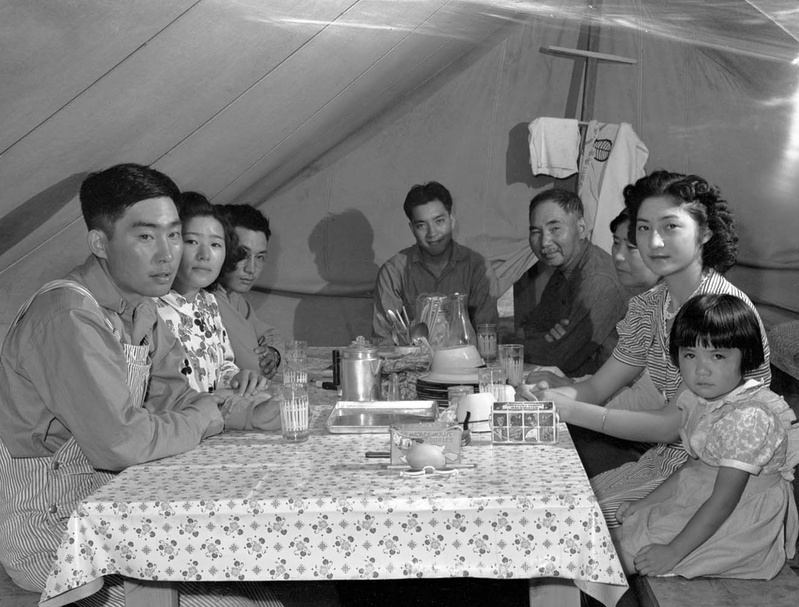

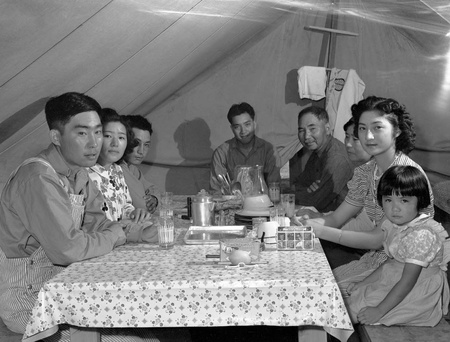

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II is a traveling exhibition produced the by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission. Featuring historical images by noted federal photographer Russell Lee integrated with video content, the exhibition examines how Japanese American laborers became an essential part of the wartime sugar industry.

Discover Nikkei had the chance to engage the exhibition’s curator, Morgen Young, for an interview about the project.

* * * * *

DN (Discover Nikkei): How did this exhibition come to be? Can you comment a bit on the exhibition’s evolution from inspiration to the completed work?

MY (Morgen Young): This project was a collaborative effort with the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission (OCHC). I approached the organization’s president, David Milholland, in 2011 with an idea to develop a traveling photography exhibit that would highlight Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer Russell Lee’s works documenting Japanese American farm labor camps in 1942. OCHC had previously organized a traveling exhibit examining Lee’s FSA colleague Dorothea Lange’s documentation of Oregon during the Great Depression.

Our work on Uprooted began in 2012. The project starting taking off the next year, after members of the Nikkei community in eastern Oregon began identifying people in Lee’s photographs. Once we had some names, I was able to record oral history interviews with people who lived in the camps, some of whom are featured in the exhibit photographs. After we received a National Park Service Japanese American Confinement Sites preservation grant, we were able to hire a graphic designer, video producers, translators, and a curriculum consultant as well as fund the fabrication and shipment of the exhibit itself. Through the effort of many dedicated people and wonderful community members, we have been able to produce two sets of our traveling photography exhibit, Spanish and Japanese translations of our text panels, a comprehensive website, lesson plans, and two documentary videos.

DN: Briefly tell us a little about your background and how you came to be involved with this project.

MY: I am a consulting historian in Portland, Oregon. My work includes historical research and writing, exhibit development, documentary films, oral history, and digital history. I work for Historical Research Associates, Inc., a history and cultural resource management consulting firm, out of their Portland office. When I began my work on Uprooted, I was running my own consulting business.

This project has really been a labor of love. I studied Farm Security Administration photography in graduate school in South Carolina. After moving to the West Coast, I wanted to sink my teeth into a project that examined some aspect of FSA photography, particularly the work of Russell Lee, who is often overlooked among the FSA photographers.

DN: How much did you know about Japanese American history prior to starting the project? Did you learn anything that particularly surprised you while you working on the project?

MY: This is my first project that focused on Japanese American history and hopefully it won’t be my last. One immediate thing I learned was the correct terminology. Like many, I referred to the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans as “internment” and I quickly learned that that was not an accurate word to use.

Throughout this project, I have been surprised at how little farm labor camps have been mentioned in the scholarship of the Japanese American wartime experience. That has been a large goal of this project—to get more recognition of the camps themselves as well as the efforts of Japanese Americans who participated in the War Relocation Authority’s seasonal leave program. These individuals and families volunteered for agricultural labor—they went into new environments, where they didn’t know how they would be received by the local communities. They contributed directly to the war effort and still have not received the recognition they deserve for their efforts.

DN: Tell us a little about Russell Lee. We know he was a photographer for the FSA, but what can you share about him that might help readers gain a more nuanced understanding about who he was?

MY: Russell Lee was different from many of his fellow FSA photographers. He had a science background—he received his degree in chemical engineering. That training helped his photography—he mixed his own chemicals, processed his own negatives, mastered the flash.

While other FSA photographers favored natural light, like Dorothea Lange, and therefore rarely photographed interior spaces, Lee was comfortable with flash photography and was able to record his subjects and where they lived. He also differed from his colleagues because he produced series of images, whereas Lange and Walker Evans were constantly looking to shoot one great photograph.

Lee has been described as a taxonomist—he used his camera to document everything he saw. He was also the most prolific of all the photographers working for the federal agency, taking some 5,000 images during the seven years he worked for the FSA.

Because of both his taxonomic approach and the sheer number of images he produced, the public now has rich, visual record of the Japanese American wartime experience. Between April and August of 1942, he took almost 600 images of Nikkei in California, Oregon, and Idaho. He was appalled by the forced removal and incarceration, but he also believed it was important to photograph what was happening, so the country would have visual evidence of the atrocities committed during the war.

DN: This exhibition is about events that happened 70+ years ago. For those who may not yet understand why it’s important to tell this story now, what aspects do you think are most relevant to current issues today?

MY: It’s important that we document and share with the public all aspects of the forced removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans. The farm labor camps are one part of the larger story. It’s important for the public to understand what happened in the past so we don’t repeat it in the future.

The anti-Muslim and anti-immigrant rhetoric that is so prolific in politics today is very dangerous and harkens back to anti-Asian rhetoric and legislation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. We need to realize that what happened to the Nikkei community during World War II could happen again and as a society, we need to do everything we can to prevent such atrocities from being repeated.

DN: What were some of the factors you considered in deciding which images to include in the exhibition?

MY: The exhibit includes 45 of Russell Lee’s 300 images he took of farm labor camps. We wanted those that we selected to be diverse, in terms of several factors. One was geography—Lee visited camps near the towns of Nyssa, Oregon and Shelley, Rupert, and Twin Falls, Idaho—so we wanted images from each camp. One was thematic—we wanted to show the various aspects of camp life documented by Lee, including camp sites themselves, everyday life, farm labor, and recreation. The last factor was people. Thanks to community members across the West Coast, we were able to identify about a quarter of the individuals featured in the Nyssa camp photographs. We wanted to include as many images in the exhibit where we could include the names of people as well as some biographical information.

In the exhibit, each photograph has two sets of captions—the original caption recorded by Lee in July 1942 and a caption I wrote that provides some background information about the farm labor program and/or the image itself as well as the names of any identified individuals. We have been unable to identify anyone in the images from the three Idaho camps, but we’re hoping that while the exhibit is in Los Angeles, people will recognize some of the faces.

The exhibit includes a photo identification binder, with all the exhibit images that have unidentified individuals featured. Museum visitors are encouraged to look through the binder to identify anyone they recognize and provide us with some details about their lives. The exhibit is that much more powerful when you know something about the people in the photographs.

DN: What have been some of the most interesting or unexpected comments or reactions that you have received regarding the exhibition or the photos?

MY: The most rewarding part of this entire project has been connecting with the Nikkei community. We debuted the exhibit at the Four Rivers Cultural Center in Ontario, Oregon. We chose this site for many reasons. Ontario is just north of Nyssa, the site of the first Japanese American farm labor camp established during the war. The presence of that camp, as well as others in eastern Oregon and western Idaho, helped grow a vibrant Nikkei community in the Snake River Valley. This project would not have happened without their help, so we wanted to honor their continuous support by opening the exhibit there first.

About three hundred people attended the opening, including many Nisei who lived in the farm labor camps, some of whom had not seen each other in decades. We have been thanked by Sansei and Yonsei who were not aware of the experiences of their parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents in the farm labor camps.

I have met and become friends with so many wonderful people through this project. A few anecdotes standout… I connected to Susan Nagai through the exhibit’s Facebook account. We had posted a post of her father, Mathias Uchiyama, as a young boy during the war. She identified him and passed along his contact information. We ended up recording an oral history with him that we made into a short documentary video: “Through the Lens of Russell Lee: Mathias Uchiyama’s Story.” He had not seen photographs of himself during the war until we showed him a series of fourteen images that Russell Lee had taken in July 1942. In his interview, Mathias walked us through those images and shared his recollections of both his family and the war. It was very moving.

In addition to the wonderful Nikkei community of eastern Oregon, we are indebted to the Nikkei community in the Portland metro area. I have been very close with the Iwasaki and Fujii families. I met sisters Taka Mizote and Aya Fujii in the summer of 2013, when they sat for an oral history interview. Since that initial meeting, they have become my adoptive grandmothers. We regularly meet for lunch hosted by the Japanese Ancestral Society and I’ve been invited to family events, including Aya’s 65th wedding anniversary and the Iwasaki family farm’s 100th anniversary, which was this July.

I never expected that this exhibit would become one of the most rewarding projects of my career and bring so many incredible people into my life.

* * * * *

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II will be on view at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles September 27, 2016 – January 8, 2017. More information about the project can be found at uprootedexhibit.com.

© 2016 Japanese American National Museum