Thirty years ago, much to my delight, two events occurred which served to encapsulate my bicultural, hapa heritage. I am the daughter of a Japanese mother and Southern gentleman father, a career U.S. Army veteran who met and married my mother in Japan in the aftermath of World War II.

While I traveled the world with my parents when my dad was in the military, I did most of my growing up in a small suburb of Memphis, Tennessee, after my dad retired.

In 1986, the Memphis in May International Festival, in addition to showcasing great barbeque and music, also paid tribute to the country of Japan. In the summer of that same year, the Smithsonian Institution’s Festival of American Folklife on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., celebrated the heritage and culture of the state of Tennessee and the country of Japan.

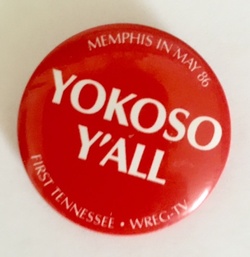

At the time, I was serving as a press aide to Tennessee’s U.S. Sen. Jim Sasser in his Washington office. I wanted to go to Memphis in May so badly that year, but wasn’t able to do so. However, a colleague who did travel to Memphis in May with our boss, brought back for me a few souvenirs he had picked up, including a button which reads “Yokoso Y’all.” I didn’t know what yokoso meant. I was more familiar with irasshaimase. I had to ask my colleague and confirm with my mom that like irasshaimase, yokoso means welcome. For me, the button uniquely reflects the hospitality of Japanese and Southern culture; both are warm, friendly, and inviting.

In the South, we say “y’all” a lot, and sometimes even its double plural “all y’all.” More than slang, for me, it’s a term of inclusiveness that is ubiquitous here.

My best friend Brenda and I often describe ourselves as half-Japanese and half-Southern. Brenda is a registered nurse and travels widely for her job with a medical research facility. Her facial features are more Japanese than mine, but her Southern accent fits in just fine here at home, never raising an eyebrow. However, when she travels, she almost always captures people’s attention with her Southern twang.

In San Francisco, she recalled a very nice waiter handing her a basket of rolls as she and a large group of colleagues were having dinner. She said, “Do you want me to pass these on down the line?” The waiter’s eyes grew large and he said, “That is not the accent I thought you would have.”

In Chicago, ordering food at a McDonald’s, the cashier simply stared at her for what seemed like several minutes, then commented, “I just can’t believe your accent, I think it’s great.” Also in Chicago, she and a colleague were walking back to their hotel and passed a homeless man holding out a cup for change. Her colleague gave the man some change, but Brenda, said, “I’m sorry, but I don’t have any change on me.” His response was, “Oh my God, let me guess, Mississippi? Arkansas? Alabama?” She said, “Close, Tennessee.” He said, “That’s not the accent I thought you’d have.” And, she replied, “I bet you thought I’d say, sorry, no speak English,” and they both laughed.

And, in Washington, D.C., Brenda went looking for a bakery and ended up in Chinatown. Surrounded by Asian customers and bakery staff, she asked, “Do you still have those blueberry tarts?” She said everyone in the bakery just froze, staring at her. Then one of the bakery staff said, “You don’t see that much in Chinatown…with your accent.”

Sometimes, people also are confused about my and Brenda’s cultural background. In Denver, Brenda was surprised when a Native American man asked her, “What tribe are you from?” And, for many years, living in the Washington, D.C., area I was often approached by Latinos asking for help, or simply saying hello and passing the time of day with me in Spanish. Luckily, I took some Spanish classes in high school and college. So, I tried my best to help when I could, and also explain that I was half-Japanese and not Hispanic.

When I was a child, my mom didn’t teach me to speak Japanese fluently. A product of her time, generation, and immigrant circumstances, she felt it was more important for me to grow up speaking only English. She didn’t want me to become confused. However, Japanese words and phrases were always spoken in our household, by all three of us. From tadaima, “I’m home,” to okaeri, “welcome back,” and itadakimasu, “let’s eat,” to gochisousama, “Thank you for the delicious meal.” Gohan also meant breakfast, lunch, or dinner, or the steamed rice my mom had with every meal.

As for my hapa friends, our dads, and myself, we all without exception are very familiar with the not-so-polite word baka spoken by our moms a lot, and we know it means stupid.

At the same time, my mom loved to laugh, telling the story of one of her trips to Japan where she was singled-out amongst her Japanese friends on a train platform by an American family asking for directions. She couldn’t understand how the family knew she could speak English and even more, after helping them, was shocked “bikkurishita” when they wanted to know where she was from, and commented that she spoke English with a Southern accent.

Back in 1986, I spent days at the Festival of American Folklife, and was treated to Appalachian and Japanese craft demonstrations, country music, and taiko drummers, as well as traditional Japanese and Southern food. There were kiosks selling Japanese items, and I remember purchasing rice candy and caramel childhood treats for myself, and a daruma, which I sent home to my mom.

I was fortunate to have the opportunity to travel to Japan twice with my mom, for three months as a teenager in the summer of 1974, and as an adult, for three weeks in the fall of 1996. Both trips were huge learning experiences. I met and learned about my family, my mom’s friends, and about Japanese history, traditions, and culture. It was on my first trip that I learned about daruma. A daruma is a round paper mache doll that can bring good luck in the fulfillment of a wish or goal. Its shape makes the doll hard to tip over, signifying perseverance or gaman. The eyes start out as blank. The left eye of the doll is colored in when a wish or goal is established, and the right eye of the doll is colored in when the wish or goal is fulfilled. I had sent the daruma to my mom so she could make a wish for herself.

I have been blind in my left eye since birth due to an irreparable illness called retinopathy of prematurity, where too much oxygen in the incubators of premature infants in the early 1950s and ’60s led many babies to become blind. In the fall of 1986, I was diagnosed with a cataract on my right eye, the one with which I am able to see. As a consequence, I went through a period of three years of progressive blindness, until 1989, when my surgeon finally decided it was time to risk removal of the cataract to restore my eyesight. The intraocular lens implant is a very common surgery today, but in 1989, at the age of 28, I was one of the youngest patients to undergo the procedure at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore.

The surgery was a success, much to my and my parents joy and relief. It wasn’t until a trip home later that year that I noticed the daruma on a shelf and saw that both eyes had been colored in. I asked my mom what wish came true, and she said that her wish was for me, that I would be able to see again. She said, “Honto ni yokatta ne. I’m so glad.”

One of my favorite Japanese words is hisashiburi. It basically means, “Long time, no see.” I learned the phrase on my second trip to Japan with my mom. She repeated it often, with such elation and exuberance greeting friends and family again after several years. To me, hisashiburi means happiness, in more ways than one.

In a way, Memphis in May and the Smithsonian Festival of American Folklife all those years ago were lovely gifts of celebration just for me. They helped me to appreciate my bicultural heritage and my uniquely American life. And, whether it’s hisashiburi or “hey, y’all,” simple words of greeting serve to strengthen the bonds of family, friendship, and community, with the universal language of hospitality that can easily bridge time and cultural divides. My “Yokoso Y’all” button is a reminder that my bicultural heritage serves as a bridge, too.

* * * * *

Our Editorial Committee selected this article as one of their favorite Nikkei-go stories. Here are their comments.

Comment from Gil Asakawa

All the entries were really well-written and impressive, but I found my favorite was “Yokoso Y’all.” The piece won my vote because of its personal, conversational voice and directness. I liked the piece starting with the title, because it told me everything about the central point Linda Cooper wanted to make.

My wife has cousins in Atlanta (and I lived in Virginia for my Wonder Years as a kid) and it’s always a marvel—although I'm not sure why it should be so surprising, really—to hear JAs speak with a southern drawl.

I also like the look into the mixed-race experience, and the cross-cultural anecdotes about being mistaken as Latina or her friend being mistaken as American Indian.

Kudos to Cooper for capturing the spirit of her life and sharing it so generously with us!

Comment from Patricia Wakida

For so many Nikkei, Japanese words are embedded into the language of their adopted country, and I loved how “Yokoso Y’all” demonstrated how fluid and delightful a hybrid language can be. Through playful anecdotes, author Linda Cooper wove a charming story of how her Nikkei roots have added dimensions of complexity to her life, and how deeply culture, both Japanese and that of the American South, uniquely combined with English and Japanese slang and phrases, has shaped her identity. Her voice is utterly her own, which is especially significant in a Nikkei Chronicles series that is focused on Nikkei-go—where words really do matter.

© 2016 Linda Cooper