This August will mark 71 years since the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The people of both cities paid for the end of the war with their own deaths and the destruction of their cities, but those who managed to survive continue to suffer the effects of the radiation left by those terrible weapons.

The war exacted enormous sacrifices from the Japanese people. Before the atomic bombs were dropped, the people of Japan had already suffered tremendously to maintain the war effort demanded by military leaders. Even though the elderly, women, and children did not participate on the battle fronts, they sustained the war effort with their work and sacrifice.

By early 1945, some of Japan’s largest cities had already been hit by U.S. bombs; Tokyo in particular was targeted by the most intense bombing of World War II, leaving more than 80,000 people dead. Homeless and lacking food, it was the people of Japan who were punished by the U.S. armed forces.

Moreover, starting in December 1941, the communities of Japanese immigrants in the United States, Canada, and Latin America, despite not being on the battlefield, were interned and persecuted. The children of immigrants—people who had been born in America but were in Japan when the war started—suffered twice due to losing all contact with their families and experiencing the suffering of the Japanese population. Some of them became hibakusha, that is, survivors of the atomic bombs.

In this article I will talk about two of them: Fernando Hiramuro, who lived in Hiroshima, and Yasuaki Yamashita from Nagasaki.

Toraichi Hiramuro, Fernando’s father, was one of the 100,000 emigrants who left the Hiroshima Prefecture for America in the first decades of the 20th century. In 1907, just 16 years old, Toraichi immigrated to Peru to work on one of the sugar plantations hiring large numbers of Japanese workers. However, rather than continue tolerating the terrible and exploitative conditions of plantation work, Hiramuro moved to Lima to work as a gardener. He saved up enough money for boat passage with the goal of entering Mexico and then crossing into the United States as a “bracero,” or guest worker.

In 1912, in the midst of the Mexican Revolution, Toraichi finally reached the port of Guaymas, Sonora, very close to the U.S. border. In this region, the U.S. railroad company Southern Pacific hired a large number of Chinese and Japanese workers to build the main rail lines that would unite the U.S. border with the city of Guadalajara in central Mexico. Toraichi joined the company as a gardener’s assistant in the small hospital built by Southern Pacific for its employees in the town of Empalme, Sonora. He later moved up through various positions until becoming a nurse’s assistant, and decided to stay in Mexico permanently.

Towards the end of the 1920s, the rail company built a large hospital in Guadalajara and sent Toraichi to San Francisco, California for training in operating an X-ray machine. In early 1930, Toraichi used his savings to travel to Hiroshima in search of a partner with whom he could start a family. Unlike most of the emigrants who met and married fiancées they knew only through letters, Toraichi traveled to his native country to meet and marry Kiyoko Hirotani.

The Hiramuro’s first daughter, Clara Sumie, was born in Guadalajara in 1931. Fernando Minoru was born two years later and Concepción Michie was born in 1939.

The Hiramuros were financially well-off, as Toraichi had worked his way up to director of the X-ray department and earned a good salary in dollars. With their savings, the Hiramuros planned to return to Japan permanently and in the fall of 1940, the five members of the family traveled to Hiroshima, where Fernando began attending elementary school. Toraichi returned to his job in Guadalajara with the goal of joining his family, now installed in Hiroshima, at a later time.

When the Pacific War began and Mexico and Japan broke off relations, all channels of communication between Toraichi and his family ended, and he was unable to send them financial assistance as well. Under these conditions, Kiyoko had to find a way to support her children. Fortunately she owned a house she could rent out, enabling them to survive the war even though each year goods became increasingly scarce for the entire population.

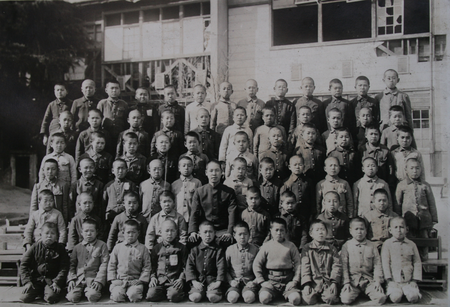

As the opposing forces came closer to the Japanese archipelago, military commanders began to prepare the population for an imminent U.S. invasion. Fernando and his neighborhood friends went to school in small battalions of five individuals led by a sergeant.

In April 1945, the government authorities decided to send students from third to sixth grades to the countryside because of the danger of bombings in urban centers. Fernando and his friends moved to Tsuta, a farming town of rice fields and streams of crystalline water located 20 kilometers from Hiroshima. The school took refuge there in a Buddhist temple. Goods were very scarce and food rationing during those months became increasingly strict: Most of the children attended school without shoes or wore sandals made of rice straw.

On August 6, 1945, when the first atomic bomb was dropped, Fernando was lining up with his classmates during the traditional ceremony marking the start of the school day, where they listened to short speeches by the teachers and participated in the mandatory greeting to the Emperor. Before the ceremony had finished, the atomic bomb exploded, at 8:15 a.m. Fernando didn’t hear an unusual noise, but he saw a light as intense as thousands of simultaneous rays of lightning, blinding him for a moment; then in the distance he saw a huge column of smoke and afterward felt the blast wave. Fortunately, the village of Tsuta was surrounded by hills, so the students didn’t grasp the magnitude of the disaster and destruction, even though the blast wave blew out all the windows of the temple.

It wasn’t until the late afternoon that the first news arrived as people began returning to the town with burns and described the massive disaster, without knowing then that it had been caused by an atomic bomb that would result in even more death over many years to come.

The students were kept at the school, so Fernando didn’t find out until weeks later that his family had survived. His mother sent him a letter in which she wrote that she and little Concepción had been attending a neighborhood meeting when the explosion occurred, while Clara, who was working in a factory alongside her high school classmates, was unharmed. However, she had witnessed thousands of deaths and the destruction of the city. Clara and the other students, fearing another explosion, fled into a nearby forest and she didn’t return home until the next day. The family home, although still standing, was tilted and severely damaged. For several days the Hiramuro family and Fernando’s grandmother had to sleep in a plantation near the house because the damage made it unsafe to sleep inside.

At noon on August 15, the students gathered in the temple to listen to an important message from the Emperor on the radio. In his speech, Hirohito announced Japan’s surrender; however, the language he used was somewhat confusing for the students and many adults didn’t clearly understand what he meant to say. It wasn’t until the following day that government authorities came to the school to explain that Japan had surrendered. The students, who like the rest of the population believed that Japan would win the war, were hugely disappointed.

In the first days of September, before the war ended, Fernando’s school returned once again to its campus in Hiroshima. That was when Fernando finally saw how badly the city had been destroyed. The roof of the train station was gone and much of the station was charred. It was a rainy day and because there was no electricity, the city was shrouded in darkness.

Classes began at the old campus the day after the return to Hiroshima, although the students and teachers spent the week cleaning and repairing the damage caused by the bomb. Students found pieces of wood and shards of glass everywhere. All of the doors and windows had to be repaired, but since there was no glass to replace them, the students simply endured the freezing wind that penetrated every classroom. Classes were only held in the morning, so Fernando had time to repair his own house, which was full of leaks. The wall panels, which were made of an earthen mixture, had fallen, so the family reattached them to bamboo mesh. With help from neighbors and several hydraulic jacks, the house was straightened once again.

For the Hiramuro family, the following years were as or more difficult than the war years. The lack of food became more severe and because the house Fernando’s mother owned in the city center had burned, they no longer received rental income from it.

Kiyoko brought a Singer sewing machine with her from Mexico, so she began sewing and repairing clothing, which most people needed because it was impossible to buy new clothes. Mrs. Hiramuro repaired hundreds of jackets and wool coats using the lining of the clothes, which was not as worn out. When customers didn’t have money to pay, they bartered various goods; Kiyoko received packs of cigarettes which she used to buy fresh vegetables and rice sold by peasants on the outskirts of the city. The famine was so severe and life-threatening that the occupying authorities requested millions of tons of food assistance, which was distributed to the population to prevent riots.

In 1946, the Hiramuro family received two pieces of good news. A letter from Toraichi in Guadalajara finally arrived after communication resumed. He told them that authorization had been given for food and medical assistance, so essential for survival, and which immigrants to America had begun to send in large quantities to their family members. Also, Fernando completed elementary school and entered high school, which was a source of great pride for the family.

That year, thousands of emigrants who, like the Hiramuro children, had been born in and were citizens of a country in America, filed requests to return. These requests were finally granted in 1950.

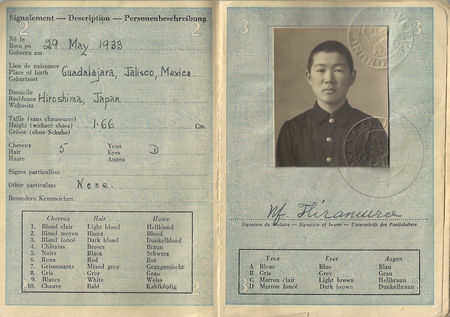

Returning wasn’t easy, since permission to leave could only be granted by the U.S. authorities. The Swedish embassy, which represented Mexico’s interests in Japan, granted the family passports so they could travel.

Toraichi purchased tickets on a boat that brought them to San Francisco, California, where he was waiting for them. The family then traveled together in first-class train coaches to Guadalajara, thanks to Toraichi’s position as a Southern Pacific employee.

The family’s reinsertion was difficult, despite their enormous happiness and relief at returning to Mexico. The Hiramuros had been separated for more than 10 years and the children had forgotten how to speak Spanish.

Furthermore, Fernando’s schooling in Japan wasn’t recognized in Mexico, so he was forced to enter sixth grade. Despite these problems, Fernando wanted to continue studying, so he decided to repeat that year and then completed high school. After graduating, he enrolled at the University of Guadalajara where he studied medicine, specializing in orthopedics. He earned his orthopedic medicine degree with the highest honors and for more than 50 years taught many generations of doctors who graduated from that university.

He married Margarita Shoji, who was born in Mexico to Japanese parents. Fernando died in 2014; his sister Clara had died in 1957. Concepción still lives in Guadalajara.

© 2016 Sergio Hernández Galindo