At the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre in Toronto there is a rare exhibition of tattoo art by the late artist and teacher Aba Bayefsky (1923–2001) and photographer Yosh Inouye until August 7, 2016.

Photographer Yosh Inouye told me:

I had witnessed tattoos in Japan. It was a frightening experience for a child. The tattoo was a fearful statement of belonging to a yakuza family.

A Japanese tattoo artist living in Toronto, Maru, arranged the first tattoo shoot for me. I visited his studio in downtown Toronto and shot without having any idea of the final image. I came back home, and stared at the photographs on a monitor. After hours passed, I started feeling comfortable. I realized I knew where to go from here. The background of my tattoo photographs is not merely background. It has an equal weight as the tattoo.

As for the work of tattoo artist Aba Bayefsky around whose artwork the exhibition is focused, it sent my memories back to when I was living in Japan (1995–2004). As I frequented the hot spring onsen and sento, I was constantly reminded about the cultural taboo of tattoos wherever I’d see signs in English saying that those with tattoos were prohibited from entering. Even today, having a tattoo means membership to the yakuza gang or, at least, designates one as an outsider, which causes a certain “discomfort” among the law abiding general public for whom conformity runs deep.

I spoke with Aba’s daughter, Edra, who lives in Toronto about her father, his life, and connection to the world of Japanese tattoos.

* * * *

I was deeply moved by your father’s story as a Royal Canadian Air Force WW2 artist, especially his deeply moving experience in Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp in Germany, which we’ll get to. First, when did your family arrive here in Canada? Where did they immigrate from?

Aba’s father came from Russia, his mother from Scotland in the early 1900s. There is a record of Aba’s father Samuel entering through Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Samuel worked as a linotype operator at the Hebrew Journal in Toronto.

Evelyn’s (Aba’s wife) parents arrived in Canada from Romania also in the early 1900s. They did not know each other at that time. Both came to join the family in Northern Ontario. Evelyn’s father, Paul Swartz, opened a clothing store in Kapuskasing. When the store burned down he went to Oshawa, at that time a quiet town, and opened “People’s Clothing,” a small men’s clothing store on the main street.

Evelyn was a student in the Department of Fine Art at the University of Toronto. It was in her fourth year, 1946, when Professor Peter Haworth, a noted Canadian artist, said one day “Miss Swartz there is someone you should meet.” It was at a night school art class being taught by teacher Aba Bayefsky, still in uniform. The teacher looked up at the young woman entering the room, and… that was it: Love at first sight!

What was it like to be Jewish at that time?

There are a couple of things that I can factually tell you about what it was like to be Jewish in the first half of the century. In 1975, Aba wrote in his journal that as the result of the 1975 “Zionism Equals Racism” resolution adopted by the United Nations, he was reminded of “the old days when I was a kid and Jew-baiting and hating were everywhere.” I remember my father telling me that at school he was beaten up because he was Jewish.

My mother came to study at the University of Toronto in 1942. She met with the Dean of Women, University College residence, Marian Ferguson, where my mother requested a roommate for her first year of study. In my mother’s words, the Dean told her “I can’t give you a roommate. How do I know who would want to room with a Jewish girl?”

How did witnessing the horrors of the Nazi death camps affect him as an artist?

Aba kept a journal from the early 1970s. An entry made in 1982 mentions fellow Jewish War Artist, Charles Goldhammer. About Goldhammer’s war art Aba writes, “One of the very few [artistic war statements] which dealt with the human side of war.” That in a sentence describes my father’s view of what he felt art should be—a statement about humanity, a statement about people’s real life experiences.

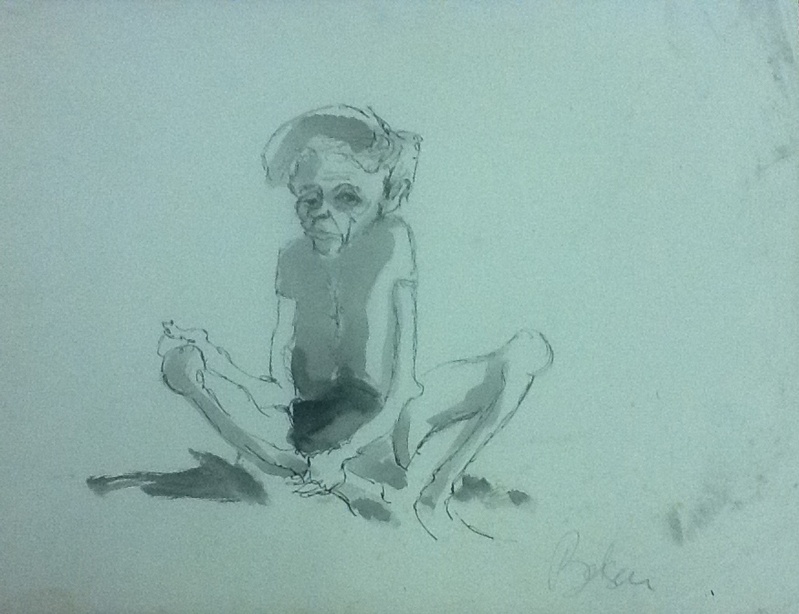

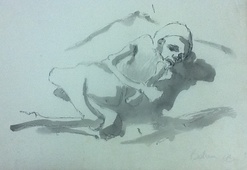

The below drawings were done by Aba Bayefsky at Belsen Concentration Camp upon its liberation in 1945. The boy sitting is a German Jewish boy and had typhus and he died the day after this drawing was made. I am not sure if the person lying down is the same boy.

Did he tell you why he chose to serve in the Royal Canadian Air Force?

In Aba’s own words written in 1997, “Shortly after my graduation, [from Central Technical High School in Toronto], I enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force and eventually after several brief postings, I was sent to McDonald Bomber and Gunnery School near Winnipeg. While I was there, I participated in a world wide art competition in the army, navy, and air force, and won a first prize in the Air Force Section. I learned the result shortly before embarking on overseas service to England where I was commissioned as an Official War Artist as a result of the competition.”

What was your Dad’s relationship with Japan? He received a Canada Council grant to visit Japan.

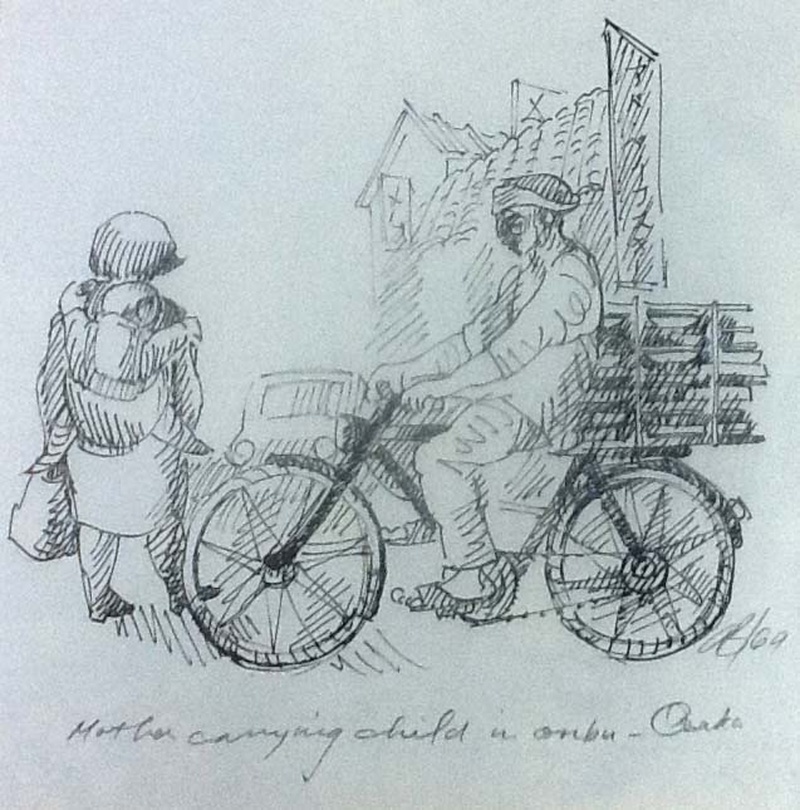

Aba went to Japan three times in 1960, 1969, and 1982. He loved Japan, the culture, the atmosphere, the people. Throughout his life he was very aware of anti-Semitism as it reared its head in different ways. So the fact that Aba went to Japan and painted there, repeatedly, signifies that he felt comfortable there, and that says everything.

How did he initially get connected to the Japanese tattoo world?

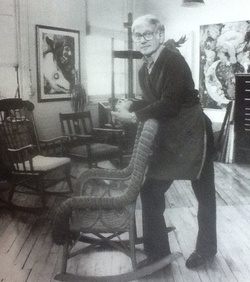

Aba Bayefsky was born in Toronto in 1923 and began drawing at the age of 16 in Kensington Market which was at that time a largely Jewish, new immigrant neighborhood. For many years marketplaces around the world including India, Israel, and Japan provided the subject matter for his oils, watercolours, and pencil sketches.

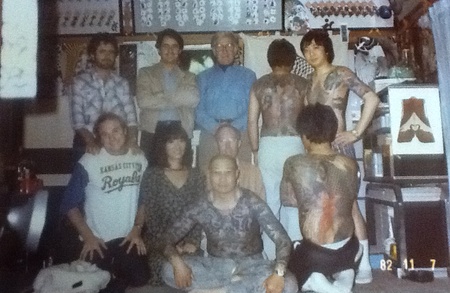

One day in the 1970s while teaching at the Ontario College of Art (in Toronto), Aba noticed something visible near the shirt collar of one of his students.

He approached to find that the student’s body was entirely covered by tattoos. This student modeled for him and re-ignited the interest begun earlier in Japan when, while painting the markets, people, and landscapes, he became interested in tattoos.

Were there any particular artists/masters that he became connected with?

Aba was drawn to Japan initially because of its expertise in the areas of print and portfolio case making, both forms of art presentation which he made use of extensively. In fact, while in Japan at some point he met the artist Shiko Munakata who did two calligraphy pieces for my parents who were in Japan together; one piece is a word meant to represent Aba and one a word to represent wife Evelyn. Both pieces we had framed and one has hung in the house hallway for many decades.

What kind of fellow was your Dad? What did he teach at OCA?

Aba developed a close and lasting friendship with two of his art students at OCA (Ontario College of Art—now called Ontario College of Art and Design) who would eventually marry, Hai Gi Hong and Duk Hee Cho. Hai Gi told me that while other teachers at OCA, along with Aba, taught illustration, very few of the teachers were capable of teaching oil painting. If I recall correctly he told me only two of the professors at OCA taught painting.

Also, Hai Gi told me that Aba met with “five” tattoo masters in Japan. I can find two names with paper evidence: Mitsuaki Ohwada based in Yokohama and Kazuo Oguri Horihide based in Gifu City.

What kind of teacher was he?

I have been told on several occasions that Aba’s students loved him. In fact, in response to an article I wrote about him in Canada’s History Magazine in 2011, one of his former students sent in a letter that was published in the following issue of the magazine expressing her warm memories of my father and his classes.

What was your Dad’s belief about tattoos as a form of art? How did the general public react?

From Aba’s own words written in 1983:

[referring to his Tattoo work]…I am having difficulty finding a gallery for my recent work done in Japan. So far everybody seems upset by the subject of tattooing and do not know how to react.

They all want an analysis of the reasons for people being tattooed and cannot seem to see the paintings as art—which it is. There is no doubt that the work is thematically unique—which should be a plus in its favour—because it looks at an unusual aspect of life—but a very real part of life—it is universally practiced and ancient in its roots. I simply refuse to do an analysis for these people who are always asking the wrong questions.

Not that I don’t have ideas about tattooed people but my work has never attempted to individually examine a life style. It is intended more as an individual observation out of which it’s probably possible to form conclusions.

It seems to be the viewers who are more inhibited than the tattooed people.

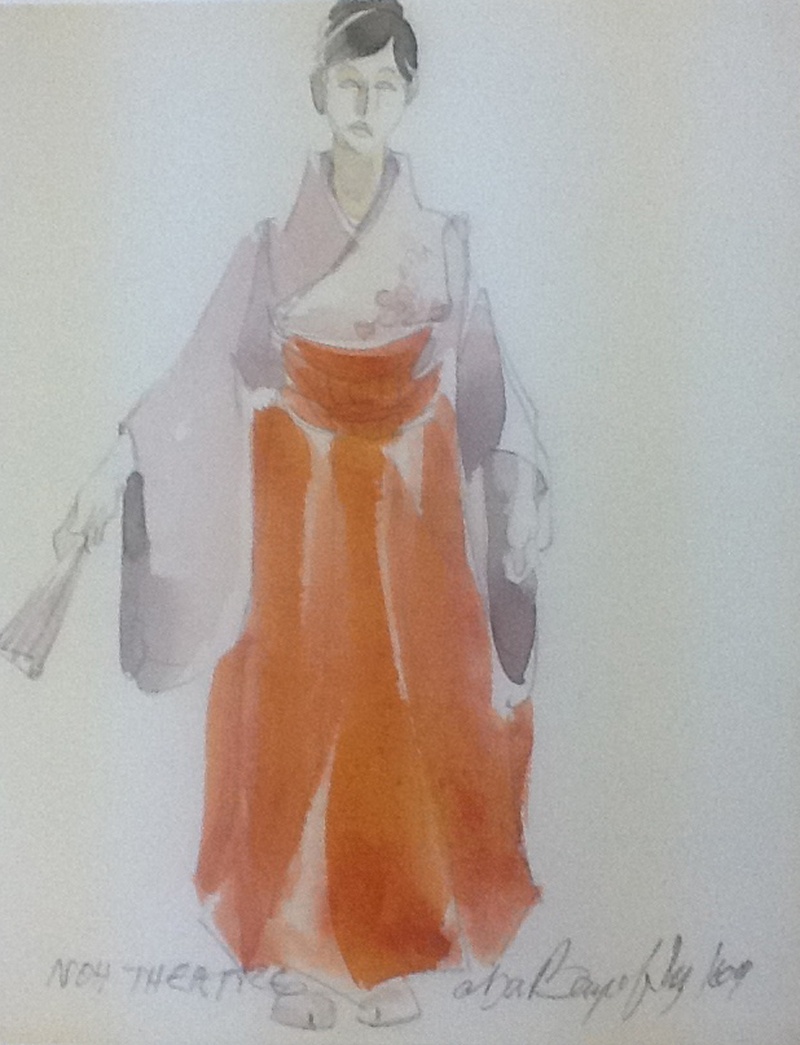

Aba travelled to many cities where he drew and painted the people, landscapes, marketplaces, and he also did a series of watercolours on a subject that fascinated him—Noh Theatre.

Did Aba himself ever have a tattoo?

Aba did not have a tattoo.

Finally, any last memory of your father that you would like to share?

Aba loved the humour of the Marx Brothers and the comedy duo Laurel and Hardy, whom he saw perform live in Paris in 1947. The humour must have been catching: At his King St. Studio, attached to a shelf supporting finished canvases, hung a song from his student days at Central Technical High School: “Take off your shoes and stockings and let your feet go bare, for we’re the boys of Central Tech and wear no underwear!”

© 2016 Norm Ibuki