The following is the story of Bill Nakashoji’s family’s experience, as he remembers it, and from what he was told by his parents and others: Bill is only 61 years old, and would not yet have been born when the expulsion process began. Alain’s information, Ms. Michi’s letter, notes from an earlier interview with Bill’s mother, and the municipality’s 75th anniversary book provided interesting and helpful supporting detail.

Bill’s father, Masaji (Joseph) Nakashoji married Chiyoko Yamada in 1941. He was a logger, and she was a household servant, in a town on the coast of British Columbia when the initial expulsion orders came from the government, under authority of the War Measures Act.

The family’s first move was to the Hastings Park “holding centre” in Vancouver, where thousands were assembled pending their distribution to “evacuation centres” in the interior of the province. Mrs Nakshojii tells what it was like:

We brought our personal belongings, but we didn’t have very much since we were newly married and just starting out. There were other Japanese people who had so much to lose – boats, houses, and businesses. The women and children were forced to stay at Hastings Park. I didn’t know where Joe had been sent and I spent most of the time worrying about him. There were guards and we weren’t allowed to go anywhere without a pass. Later I found out that the government had sent the men to Slocan Valley and other locations in the Interior to build houses for their families. The wait was long and I was afraid.

Apart from what they could carry, the possessions and properties of those expelled were turned over to the Public Trustee, supposedly for safekeeping. These included hundreds of fishing boats and many acres of prime farmland in the Fraser Delta. However, these were all subsequently sold off under dubious circumstances, and the proceeds were, it was said, used to cover the cost of housing and feeding the evacuees!

In the spring of 1942, the family was reunited, and moved to an evacuation centre at Lemon Creek, a “ghost town” in the Slocan Valley. Although the first evacuees had to live in tents, the Nakashoji family was able to go into wooden buildings, some of which Bill’s father helped build.

This was their home until the war ended. When that time came, the people in the camps were given a choice: “return” to Japan (many of the people involved were Canadian-born; many others were Canadian citizens!); or move to locations in eastern Canada (returning to their homes on the Coast was not a permitted option).

Having decided to remain in Canada, the family was soon moved again, this time to a relocation centre at Neys (a former German prisoner-of-war camp), on Lake Superior west of Marathon, Ontario.

By now, the situation had changed enough that the Japanese-Canadians were much freer to make decisions about where they would work and settle, as long as they remained east of the Rockies. With his experience in the forest industry, Bill’s dad was naturally inclined to seek logging work, and he may have done so for a time near Pigeon River, Ontario, although it is unclear whether the family went there as well.

The big opportunity, however, came when recruiters from Spruce Falls Power and Paper Company, which operated a pulp mill at Kapuskasing, came to the Neys camp in the fall of 1946, seeking bush workers. Some twenty families accepted the company’s offer. Bill’s mother comments:

We were happy to go anywhere to get settled. It didn’t matter that we’d never even heard of Kapuskasing. A large group of us [Japanese Canadians] were going together.

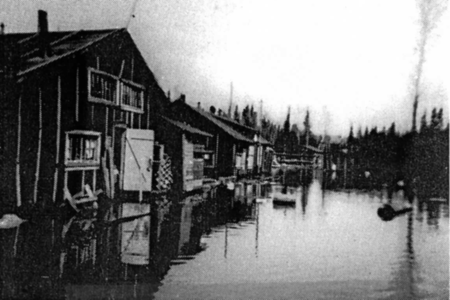

Some of the families were housed temporarily in a hotel in Hearst; others spent nearly a year at the Spruce Falls Camp 32, on the Opasatika River, some ten miles south of the village. Neither location was suitable for families (Camp 32, previously occupied by company bushworkers, was a group of tarpaper shacks on stilts right on the shore of the river, which flooded every Spring).

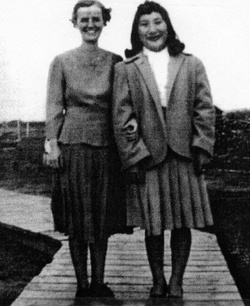

But the company provided schooling, at least at Camp 32, with Ms. Michi Ide as teacher. And the company was building much better quarters for the newcomers, just south of Opasatika, in an area that had been settled in the 1920’s by families coming from Quebec, reportedly under the auspices of the Catholic Church.

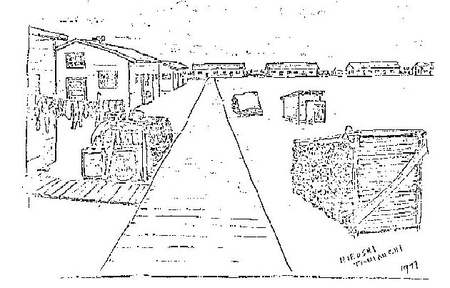

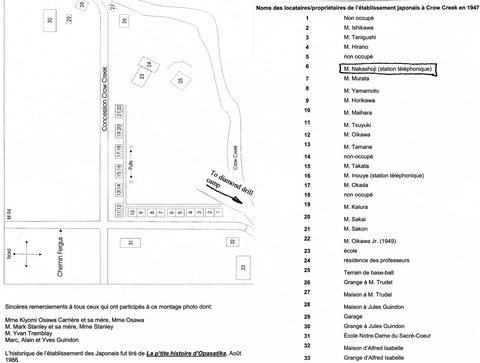

Thus began the settlement of Crow Creek in 1947: eleven dwellings housing two families each; and a primary school with Ms. Ide and Miss Foster (an Anglican missionary, who had accompanied the group from Lemon Creek) teaching the Ontario curriculum, in English. Nearby was a Catholic school and a small general store operated by Mr. Isabelle.

Two dug wells, privies, oil and wood stoves, and coal oil and Coleman lamps provided the household services to the inhabitants. There were two telephones in the camp, one of them in the Nakashoji house. There was a large playground and ball diamond – Hon. Rene Fontaine of Hearst remembers playing ball against the Japanese-Canadian boys from Crow Creek.

There were many good things about the settlement (if one sets aside the fact that its inhabitants were forced from their former homes in British Columbia!). The men had steady work and decent wages; the families were safe and warm, albeit somewhat crowded; the children had wonderful recreational opportunities, from baseball to fishing; and the relations with the area’s francophone population were a pleasant surprise to the newcomers. There was a great deal of interaction between the local children and the Japanese-Canadian students – in fact, some local children attended the Crow Creek school, to help them learn English.

Over time, families began to leave the settlement. Joe and Chiyoko moved only as far as Kapuskasing (where they raised seven children). Several other families also remained for a time in the region. Others left for opportunities in southern Ontario, and some moved back to British Columbia. Joe’s father and mother moved to Kelowna, British Columbia – nearly a half-century after being forced to leave their home province. Some families from Europe came to the camp in its later years. Like the original inhabitants of the settlement, they had obtained work with Spruce Falls. One picture in the Opasatika book shows Alain Guindon’s father teaching a European newcomer how to sharpen a swede saw!

The settlement lasted until 1957, when the last resident moved to Kapuskasing. Spruce Falls removed the buildings, and some of them may still be seen in Opasatika and Kapuskasing, although they have since been modified so much that they are hard to identify.

Bill believes that he is the last of the settlement left in the region – a view borne out by John’s search of the telephone book. His son Glen, married to a francophone, lives in Timmins; his mother, who is 86, lives in Kelowna.

Earlier in this story, we mentioned that we had used the telephone in 1952 at Crow Creek, and then noted that there was a phone in the Nakashoji house, and that we had met a boy outside the house, carrying pails of water. You guessed it – the boy was Bill Nakashoji; and it was a great thrill for the three of us as we slowly realized, as the story unfolded, that we shared that half-century-old link to that night at the Crow Creek Settlement.

Finally, we have already mentioned the positive local relationships that existed during the life of the settlement, and it was a pleasure to see that feeling prevail today. Partly through his 34 years with Northern Telephone, Bill seems to know everyone in the area, and the mutual respect and affection was very much in evidence.

It has also been a source of wonder and admiration that in all our conversations with Japanese-Canadian sources, we heard not a word of anger or complaint about the treatment their families received during that unfortunate and unwarranted suspension of their civil liberties during and after the Second World War. They do, however, share our view that such a thing should never happen again in our country.

Many thanks to all who helped us in our search! Also, a special thanks to the Municipality of Opasatica, for making available illustrations from 75 ANS DE BONS SOUVENIRS.

© 2016 George Tough