Growing up Nikkei has been both a curse and a blessing.

The generation that bore the brunt of the most ‘cursed’ aspects of being Asian immigrants was the early generations that faced the full force of racism and systemic bigotry that were openly practiced by the media (taking every opportuinity to incite hate towards us e.g., the wanton use of “Japs/Nips”), society in general, and every level of government that did their best to marginalize/exclude us from the mainstream of society (e.g., the professions) and even exile Japanese Canadians out of existence after World War Two by sending us “back home.”

The ‘blessed’ part then is that in 2016 we have, somewhat, emerged from those dark ages and are moving, perhaps, towards better times, despite on-going race issues like “Black Lives Matter” in Toronto and that which our First Nations brothers and sisters suffer across Canada. There are the looming and growing issues of racism and hate that US Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump is fomenting.

So, when it comes to discussions about race in 2016, where do JCs see themselves in the mix and what are they doing about it? Or, do they suffer from racialized tunnel vision?

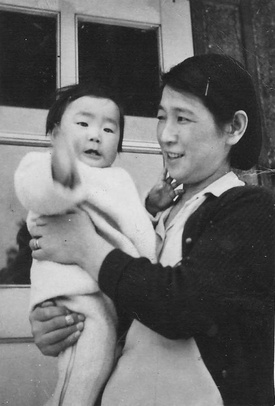

American Nisei Diana Morita Cole, 72, as a baby, was labelled “Enemy Alien” by the US government and was a prisoner at the Minidoka Concentration Camp. Diana wrote a book, Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit, about her experience.

Even at the end of WW2, the community of Hood River, Oregon, made it clear that Japanese Americans were not welcome back ‘home’ (although not legally barred from living there). Instead, the Morita family moved to Chicago, Illinois where their Horatio Alger story continued amongst other marginalized and disadvantaged (including African Americans, Hawaiian Japanese, European Jewish) groups in the slums of the ‘Windy City’ in the days that would lead shortly to the emergence of leaders Martin Luther KIng, Jr., Malcolm X, Rosa Parks and the Civil Rights movement.

* * * * *

First, can you please tell us a bit about yourself?

I have earned a diploma from Royal Conservatory of Music Diploma in piano and a bachelor’s degree in English literature, graduating summa cum laude. I successfully ran a music studio as a piano teacher for several years in Belleville, Kamloops, Sault Ste. Marie and served as the President of the Sault Ste. Marie branch of the Ontario Registered Music Teachers Association. I have worked many years as a researcher in libraries and at the Canadian Diabetes Association, London branch, for the Native Program. I was an IT consultant for thirteen years in London, Ontario — attaining Novell Administration and several Lotus Notes Specialist designations. I also worked as an International Student Advisor at a university in Eastern Canada.

How did you end up living in Nelson, BC.? Did you know anything about the Kootenays JC internment past before arriving there?

My husband, Wayne, and I moved to Nelson in response to our inability to continue living in Cape Breton, a society that enjoys calling anyone who moves there a “Come From Away.” CFA is the acronym used to distinguish people like us from those who have lived on the island for generations. If you were born in Cape Breton, move away, and decide to return, you too would be considered CFA. That’s how insular that society is.

On the advice of a friend who told us he thought Nelson would be a good place to live, my husband, Wayne, discovered an ad for a Chief Librarian position at the Nelson library on the internet. We flew out to BC for an interview and saw what a beautiful town it was. We were told that a large number of expatriates lived in Nelson and in the outlying areas, so we felt the community might be more to our liking. Nelson is considered Canada's best small art town, so we enjoy the stimulation of writers and artists in the area. The outdoor recreational activities are wonderful: we like the rigorous cross country skiing trails at the Whitewater Ski Resort (the powder is world class!), bicycling along the Slocan River, and swimming in the icy waters of Kootenay Lake.

Before coming to Nelson, I had read Ken Adachi’s The Enemy Who Never Was, Metamorphosis: Stages in a Life by David Suzuki, and Obasan. But at the time, we had no idea the Kootenay was filled with ghost towns that were deemed suitable for detaining Japanese Canadians who were expelled from the coast. It was particularly chilling when we drove into Sandon on our way to explore Idaho Lookout.

What inspired you to write your memoir? Did you write this for a particular audience e.g., younger Nikkei? Family?

I had been struggling to write the story about my confusing identity for a very long time. Not only had I been struggling to write my story, but even more, to figure out just who I was as I wrote my memoir.

I’d written several essays about my life, but never thought about turning these essays into a memoir until I began to write in the company of other immigrant women writers in 2011. No one was more surprised than I was when they welcomed what I disclosed about my life in a culture that denied the values I was taught at home. These ladies knew what it was to feel like misfits.

And so too did many others, I discovered at my launches subsequent to self-publishing my book, Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit, in September of this past year. I’ve learned you don’t have to be a visible minority to feel you don’t belong.

As I continued to write my story, I realized that it might prove interesting to my nieces and nephews and especially, to my own son. But that was not my original intent.

What was life like for your family in Hood River, Oregon and Minidoka Concentration Camp?

My father, Mototsugu Morita, loved the Hood River Valley and the orchard he tended on his farm. I remember as a young girl growing up in Chicago, seeing the valley through his eyes. And then years later in the early 90’s, I had the good fortune to visit Oregon for a family reunion. The valley was beautiful and green, just as my father described it. I loved seeing the mountains and the Columbia River he’d portrayed in his stories.

Minidoka Relocation Center, where I was born, was one of the ten concentration camps established by the War Relocation Authority to illegally imprison 9,000 innocent Japanese Americans, deemed to be an imminent threat by the US Government during World War II. Minidoka was established on 950 acres of barren land in what was then considered Shoshone territory, 15 miles north of Twin Falls, Idaho. There was a canal that bordered the north side of the encampment, making it unnecessary for the government to erect barbed wire fences along that portion. I’ve no recollection of the concentration camp except through pictures and the stories my family have told me about being forced to live in a that desolate place, bereft of their friends, their toys, and the comforts of home.

I look forward to seeing Minidoka for myself at the end of June this year when I will give a presentation during the Minidoka Pilgrimage. Of course, all the original buildings are long gone, and now, ironically, it has been given the distinction of being named a national historical site.

Any thoughts about the lasting Impact and legacy of internment?

The impact of the expulsion and captivity on my parents and siblings was profound. When they lived on the farm in the Hood River Valley, I believe they were untouched by the anxiety caused by the war. My older siblings were affected by the insecurity of poverty and racism in the Hood River Valley, but not to the degree they became traumatized after FDR issued Executive Order 9066. Until then they were farm kids dealing with survival in a rural setting, and they even had a few white friends. Then after the expulsion and imprisonment, their status as a visible minority became more pronounced. They knew they had become political pariah.

On the other hand, my mother, Masano, was deathly allergic to alfalfa on the farm, was freed from that affliction after she was displaced.

My mother was forty-four when I was born and my father was fifty-one. By the time the war was over, my father’s position in the family had deteriorated to the extent that he was unable to convince his children to return to the place he loved in Oregon. He became what I thought to be a broken man, although he still loved to laugh, tell stories, and visit with his friends. He had lost his identity as an apple grower and never found the equivalent joy in the jobs he found in Chicago, where he worked making rattan furniture and also in a factory, alongside my mother, making fiberglass insulation.

My siblings’ adaptation to living in Chicago after they were released from Minidoka in 1945 was to become insular and mistrustful of the external community from which they were barred during the war. They became overly compliant whenever they felt exposed and vulnerable to the world beyond our apartment door. I remember, for example, they’re being especially careful to place the items for purchase in the proper order on the grocery checkout counter and being exceedingly deferential to the clerk. They’d always make sure to have the right amount of money in their hands before being asked for it since they wanted to avoid calling attention to themselves in public.

My sisters, Flora and Betty, had told me about their good friends in Hood River: Margie Bryan and Nancy Odell. But I never saw them socialize with white people when they were adolescents in Chicago. It’s all very understandable, of course, being traumatized as they had been and being excluded from places, like the tennis courts in Chicago. So they joined ethnic social clubs and athletic teams organized by Abe Hagiwara, a wonderfully humane social worker who worked at the Olivet Institute. These groups helped my unmarried siblings develop a sense of belonging that they wouldn’t otherwise have had while they were forced to integrate into a new urban reality. They learned to enjoy bowling, an indoor sport, where they were less conspicuous and less of a social threat to the white community in Chicago.

But by the time Betty, Flora, and Junior were teenagers, my eldest siblings, Dorothy, Ruth, Paul, and Claude, had married and lived separately from my grandfather, parents, younger siblings and myself.

I was excluded from their social club activities, which I couldn’t understand. I was very precocious and grew up isolated, listening to love ballads sung by Billy Eckstein and Nat King Cole on the 78 rpm vinyl records they’d collected. I also felt conflicted about my relationship with my parents and grandfather since I was forced by virtue of my education to interact with white children at Ogden School and by my attendance at Elm-LaSalle Church.

Compared to my siblings, I was a loner in the family. They wouldn’t think this but I was pretty much forced to come to terms with our new surroundings on my own, which meant on the streets of the Near North Side since my parents were working and didn’t understand Chicago or the larger community we lived in. And at the same time, I had to work out my position in my family as it grew to include my siblings’ children. So I became the family babysitter for my younger nieces and nephews.

The neighbourhood we lived in was a truly diverse community, one that couldn’t have been engineered by social policy. As strange as it was, there was a richness of experience that I could not have enjoyed anywhere else. It made me, by necessity, a far more open-minded person than I would have been if I’d grown up in Hood River, say.

Thrown on my own, I was vulnerable to the influences of the media, which likely corrupted me to believe in the American Dream––which, as we all know, doesn’t exist. As George Carlin says, “They call it the American Dream because you have to be asleep to believe it.” But you don’t understand the lies you were being fed when you are a child until you grow up and are forced to think critically about your country.

Growing up with white friends and watching TV and movies, I began to pretend I was white. That is, I was attempting to overcome my racial angst and ease my sense of estrangement by pretending I was someone else.

And unfortunately, the gruesome samurai movies my parents took me to see as a youngster at the Greek Orthodox church did nothing to inure me to the Japanese culture, which I believed stood in the way of my acculturation. What kind of people would revel in revenge, suicide, and swordsmanship?

But, boy, did we ever learn to excel! With the Japanese work ethic I seemed to inherit by virtue of my DNA and early training at home, I, like all my Nikkei friends and relations, competed in school and was always at the top of my class. Excelling was the one way I could relieve my sense of estrangement and gain a sense of privilege in school that I lacked in other settings.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki