The divide between the “haves” and those with less was never more evident in the peatlands than when the gun clubs arrived. Past the western edge of Wintersburg’s farmland, the Bolsa Chica Gun Club was among the most prominent, boasting a wealthy, eclectic membership.

For the Okuda family, the Bolsa Chica Gun Club was home for over two decades. Harry Okuda maintained the landscaping and kitchen gardens, including the yard of chickens being readied for club members’ dinners. Harry arrived at the Gun Club circa 1910 or 1913—coinciding with his arrival in the United States (note: family memories which place arrival at 1910 and information written by the census taker differ, not that unusual for the time).

The 1930 census for Wintersburg Village included the Bolsa Chica in its enumeration and listed Harry “Okuta” (age 53) as a “Chica Gun Club gardener,” his wife, Aekeno (age 40), Bill (age 11), Jimmie (age 9), and Irma (age 6).

Seventy-five years later in 2005, Dave Carlberg—author of Bolsa Chica—Its History from Prehistoric Times To The Present—sat down with then 84-year-old Jimmie to talk about his life at the Gun Club. Carlberg wrote about Okuda in the Amigos de Bolsa Chica’s summer 2005 newsletter, Tern Tide.

“Okuda’s family was one of the few clubhouse staff who actually lived on the gun club property,” explains Carlberg. The Okudas lived in a house below the clubhouse. Jimmie was born in 1921 and spent his early childhood years on the Bolsa Chica.

“When not attending school in Huntington Beach,” Okuda told Carlberg, he spent his days “fishing and swimming in the lagoon, helping tend his mother’s chickens or enjoying sunsets from the beach.”

“At times he would help his father care for the landscaping around the clubhouse, including a nine-hole golf course. Young Okuda watched as lines of chauffeur driven Duesenbergs, Cadillacs, and Buicks dropped off bankers, industry leaders, sports figures, Hollywood stars, members of the 1932 Los Angeles Olympic Committee, and even royalty. One slim, ordinary looking gentleman Okuda observed entering the clubhouse, the eleven-year-old was later to learn, was the Prince of Wales, two years later to be known as King Edward VIII of Great Britain.”

An exodus of khaki-clad men

By 1905, it is reported there were 23 shooting clubs in Los Angeles and Orange counties devoted to duck hunting, the Bolsa Chica being one of the wealthiest. The October 15, 1905, Los Angeles Herald reported the opening of hunting season: “There was an exodus of khaki-clad men from Los Angeles last night. Trolley cars and trains took them away by hundreds, and automobiles and livery rigs conveyed scores to the chaparral and the club houses by the shores.”

“Down at the club houses last night,” continued the Herald, “there were merry crowds of sportsmen who burned good tobacco and drew the long bow until the momentous hour when the dice were rolled for the first choice of blind and first gun.” (For our 21st Century readers, “drawing the long bow” means they were telling a few tall tales or heavily embellished stories about their exploits.)

During the start of the 1908 hunting season, the Los Angeles Herald reported, “On most of the preserves the club houses and lodges are comfortably—some even luxuriantly—arranged with kitchens, snug sleeping quarters and elegant dining rooms.” The previous year, the September 29, 1907, Herald had noted “quantities of food supplies have been laid in, to say nothing of liquid refreshments, the latter to prevent members of taking cold when they get wet. Needless to say, all hunters will be very cautious not to fall into the water or get their feet wet.”

Early morning hunts

Okuda talked with Carlberg about the hunters being taken out in the early morning “to the fresh water ponds that covered much of the Bolsa Chica. Instead of using dogs to retrieve downed ducks, local boys in hip boots were hired to do the work.” Okuda told Carlberg he was “too young to play bird dog,” but he sometimes tagged along. Okuda remembered “the awesome sight and sound of several thousand ducks suddenly taking flight when startled by gunfire.”

Members of the Club

Memberships in the Bolsa Chica Gun Club initially started at $1,000, then later rose to $75,000, making the club more exclusive. Some of the 3,400-acre Bolsa Chica Gun Club members were staggeringly wealthy for the time, valued for their sporty quality, or that they were conveniently well connected. Among them:

- Hulett C. Merritt, described by the December 11, 1910, Los Angeles Herald as a “millionaire and financier” in an article about the planned Merritt Building in downtown Los Angeles. At the time, Merritt was pushing city leaders to waive building height restrictions from 180 feet to 233 feet. Merritt is reported as saying he would scrap plans for the Italian Renaissance-style monument to his family unless he was allowed the height variance, otherwise “it’s beauty will be marred and I want to build for the artistic value more than for any profit I may get out of it.” Originally from Minnesota, Merritt had sold his interests in the Merritt-Rockefeller syndicate in 1891 for more than $81 million.

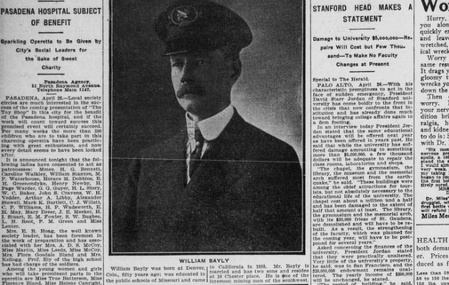

- William Bayly, a colleague of H.E. Huntington, Bayly helped develop the West Coast’s version of Naples. The Bayly’s European travels, soirees, and “delightfully appointed” luncheons at 10 Chester Place were regular features of Los Angeles’ society pages.

- Dr. G. MacGowan, a Los Angeles physician, once attacked by a Mrs. Robertson with a horse whip. As reported in the April 18, 1896, San Francisco Call, “The doctor today received a note from the woman…‘I warn you not to say anything further about the insanity theory’ intimating there would be more horse-whipping if he attempted to prove her insane.”

- Gail B. Johnson, a board member of the Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce, Vice President of Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company, a director of the Sinaloa Land Corporation, and director of German American Savings Bank (later First National Bank).

- J. S. Torrance, multi-millionaire Pasadena resident and director of the Pacific Steel Company. Brokering deals for Home Telephone Company, Torrance was questioned by the San Francisco grand jury in 1907 for a fund of $300,000 “for use in bribing the supervisors to grant the Home Company the competitive franchise.” In California In Our Time (Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1947), Robert Glass Cleland writes, “under the state’s promise of immunity, eighteen of the supervisors confessed the wholesale acceptance of bribes, not only from the organized activities of the underworld but on a still larger scale from public utilities and other corporations doing business in the city.”

- C.P. Moorehouse, a Pasadena sportsman, he is reported by The Herald, July 12, 1896, to have taken a 137-pound tuna in Catalina Island’s Avalon bay “after a four hour fight.”

- J.D. Thomson of Pasadena, Premier and Mascot Oil Companies, Hidalgo Oil Company, and Boca del Cobre and Sierra Pinta mining companies.

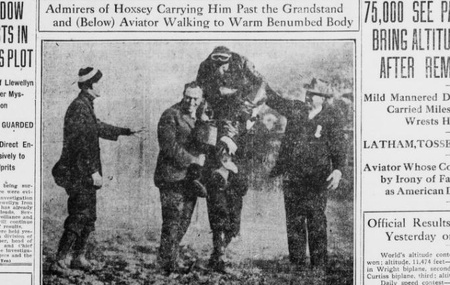

- Isaac Milbank, member of the Dominguez Field aviation committee, a director of the Sinaloa Land Corporation, and a director of the Pacific Mutual Life Insurance Company. Milbank was involved with the aerial duck hunt over Bolsa Chica by French aviator Hubert Latham, December 23, 1910, and was present four days later when American aviator Arch Hoxsey broke the world record for altitude in a Wright biplane, 11,474 feet. Latham crashed his Antoinette monoplane at a windy Dominguez field that day and set the remains on fire.

- James Slauson, a member of the Southwest Society of the Archaeological Institute of America and the Los Angeles Municipal Music Commission.

- H.L. Story, of Story & Clark in Chicago, vice president of the National Association of Manufacturers, president of the Railroad Men’s Railway Company, and member of the Pasadena Audubon Society.

- M.J. Connell, president of the California Fish and Game in 1910. This presented an awkward situation when the commission considered banning aerial duck hunting after the December 1910 aerial duck hunt over the Bolsa Chica by aviator Hubert Latham.

100 Dam Years

As glamorous as the Gun Club may have been, not all were happy with its presence. In order to create bigger duck ponds, the Gun Club blocked the natural tidal flow, quickly incurring the wrath of peatland ranchers and farmers.

In August 1907—after years of fighting and legal actions—the over 40-member Bolsa Chica Gun Club offered a $500 reward “for the arrest of the persons who scuttled its dredger in Fremont Creek last week…trouble between the farmers in the vicinity and the club members arose after the dam was built…” It was a dispute that continued for a century.

It would not be until 2006 that a wetlands restoration project re-opened the tidal inlet blocked by the Gun Club. In the darkness of dawn—the time when early 1900s duck hunters would have tromped out to the ponds—locals of the former peatlands watched the tide return and cheered the return of saltwater to the wetlands.

A childhood on the Bolsa Chica

It’s not likely a young Jimmie Okuda was aware of the going’s on in the lives of the Gun Club members or of the politics regarding the dammed tidal inlet. He was living an ideal child’s life with wetlands and fields to explore. Okuda’s family worked and lived on the Gun Club property until 1935, when his father, Harry Okuda, lost his job due to an injury. Jimmie was then 14 years old.

“The family was desperate. These were depression years and there was no work,” writes Carlberg. “Then Okuda’s mother realized that the experience the family gained raising chickens at the gun club would get them through hard times.” The Okudas bought a small farm near present-day Brookhurst Avenue and the 22 Freeway, and by 1941 “their chicken farm was operating in the black.”

Then, World War II. Like most of Wintersburg’s and Orange County’s Japanese Americans, the Okudas were forcibly removed from California and confined during WWII. The Okudas were sent to the Colorado River Relocation Center at Poston, Arizona. Okuda told Carlberg the family turned the farm over to their chicken feed supplier. Fortunately, the Okudas were able to regain the farm when they returned to Orange County. They moved the farm to the area of Hazard Avenue and Bushard Street—due to the construction of the 22 Freeway—before retiring it to urbanization.

In 2005, Okuda told Carlberg he had taken up a game favored by the gun club members—golf—and had become a world traveler. Jim Shigeru Okuda passed away in 2007 in nearby Westminster, with funeral services held at the Wintersburg Presbyterian Church (the former Wintersburg Japanese Mission).

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on May 16, 2012.

© 2012 M. Adams Urashima