Language is the homeland of any poet. Perhaps that is why Juan Carlos de la Fuente Umetsu (Lima, 1963) has so much to say when he writes and speaks. His surnames in themselves have a meaning and a story that fits into his verses and dialogue, which immediately refer to the mysteries of his writing and to a charming man for his wise simplicity.

He started writing at a very young age (at age eight) and still repeats that poetry is a necessity for him, although he doesn't know if he likes writing or reading more. Both sides of the coin come to light in his official biography: he studied Law at the Universidad Mayor de San Marcos, although he spent his time at the Faculty of Letters; He was a journalist, edited poetry magazines and has won and been a finalist in several contests with his verses.

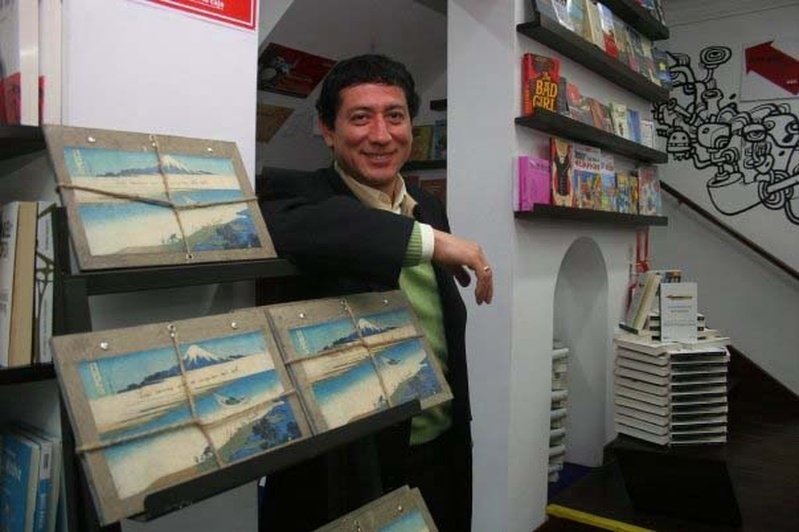

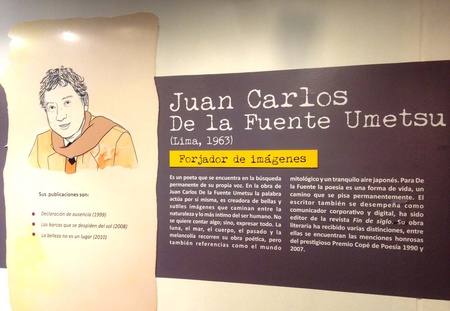

But Juan Carlos maintains that the poet is outside of awards, fashions and currents. While his fourth collection of poems is being edited, which will be released this year, the current head of Digital Relations and Communication of the company Telefónica del Perú, who has just been included in the exhibition Nikkei Peruvian Writers: Literary profiles and illustrations about nine authors nikkei , included in the Third Nikkei Cultural Festival of the Peruvian Japanese Cultural Center, returns to his memories and words.

Japanese origin

“Perhaps the most literary thing in my life is my Japanese surname. Perhaps for this reason I am a writer and more precisely a poet.” On the occasion of the aforementioned exhibition, Juan Carlos has written a text about his grandfather Makiso Umetsu, that mysterious man who called himself Vicente in Peru, who worked with the Japanese businessman Seguma Kitsutani in Lima, and who was deported by the Second World War.

Umetsu, says the writer, means 'port of plum trees', 'temple port surrounded by plum trees' or 'the man who lived near the sea and grew plum trees'. He wrote to his grandfather the poem Apology of the Hero (now lost) and that oriental heritage that, he says, “is manifested unconsciously” and that is present in his life and work, is from which he cannot be separated. “My grandmother Amalia Lostaunau, born in Piscobamba, Ancash, taught me to read the time on a clock that played the Japanese anthem at noon.”

“In fact, I began to become more interested in things Japanese because of a book by the Peruvian poet Javier Sologuren.” That book is the anthology “The rumor of the origin”, a sample of the most significant of Japanese literature in all its genres and periods, which introduced De la Fuente to haiku and other Japanese poetic forms. Brevity and aphorism are oriental influences that his poems will have, through which a reflective and contemplative spirit travels at length.

poetry time

Although in 1981, at less than 20 years old, he had already become known when he was awarded in the poetry contest of the Municipality of Lima (and in 1985 when he won the Manuel González Prada contest and obtained recognition in The Young Poet of Peru ), his first collection of poems was only published in 1999. From Declaration of Absence (Asalto al Cielo Editores) there is surely a lot to say but there is something that comes to the writer's mind: his shyness and that sense of isolation he had until He entered the world of journalism.

He was first in El Observador and then in the supplement El Cultural , of the newspaper El Peruano , in the early nineties, where he shared the editorial staff with great journalists such as Willy Pinto Gamboa, Fernando Obregón and Paul Nakamurakare. “I remember that we paid the poets we included in the anthologies, it was something that has never been done,” says the person who also edited the literary magazine Fin de Siglo and collaborated with other newspapers in the country.

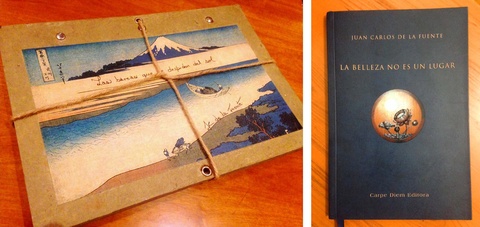

From those years, and from his time at the university, Juan Carlos keeps friendships, gatherings and many readings that formed his literary background, the one through which Matsuo Bashō but also Garcilaso de la Vega and Constantino Cavafy passed. The Japanese, once again, is revealed with Las barcas que se desdede del sol (The Latino Press/Tranvías Editores, 2008), a numbered book-object on whose cover appears one of the 33 views of Mount Fuji by Katsushika Hokusai, and whose prelude pray:

The ship travels on its own, the wind seduces the roads, the heroes lie on the beach of a dream, soft as a sword abandoned in the sky. celestial turncoats who silence the first word. The man in his shoal feels. They row their ideas with the light of a river. The stone sings, the bird wakes up and crosses the night with its gaze. no shortcuts are needed. The man is standing next to your door and eternally shouts for you to open it.

there are fish holding the colors of the water

The eastern margin

“A great contribution of Eastern culture is the option of emptiness,” says Juan Carlos. While in the West emptiness is lack, loss and depression, in the Asian vision emptiness is plenitude, encounter and illumination. “The function of art is to heal,” he says calmly before proposing that Nikkei poetry be demystified, which in Peru makes immediate reference to the great José Watanabe but which should also lead to other names.

Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Alberto Hildago and Sologuren himself have also done a lot for Japanese and Nikkei poetry in Peru, he believes, making a list that could well have his name towards the end. His third collection of poems, Beauty is not a place (Carpe Diem Editora, 2010) went to press after being chosen among the honorable mentions of the prestigious Copé Poetry Prize in 2007; a recognition that he had already obtained in 1991 and that was just awarded again in 2015, for a still unpublished book.

“For more than 20 years, Juan Carlos de la Fuente has been traveling through this world with poetry, as a particular way of living, feeling, breathing,” says the back cover of his latest book, “a harmonious set of verses that It structures a reflective poetry, with beautiful images and linguistic and visual signs that it develops within the metaphysical insularity.” One of the poems in this publication, dedicated to his son Mario Sebastián, is called “Extravíos” and has the air of haiku :

I walked towards you

With the certainty

from a tear

The tear dried

I don't know how to find you.

The poet's place

The poet in transit opens his briefcase and takes out a couple of books by the Korean philosopher Byung-Chul Han, who is considered the next Jürgen Habermas, and talks to me about the present, which has not kept him from journalism, although he is now in a position more institutional in which it never fails to find a space for reflection. “The future of any company lies in having a humanistic perspective,” he states with conviction.

Making proposals that are not only for consumption, but also to fulfill ourselves as human beings is the message they should give, says Juan Carlos de la Fuente Umetsu, who is also convinced that new information and communication technologies are the tool to achieve this. . In fact, he adds, he has a blog ( Noticias del interior ) in which he presents poets from different parts of the world, he buys many books online and has written his latest book with the notes application on his smartphone.

Is there a place for poets and philosophers in big companies? He agrees yes because of the different contribution they can give. In an increasingly horizontal world, where everyone wants to be unique and ends up being equal, the intellectual brings that discordant voice, in the same way that a book like Las barcas que desdedede del sol , with pressed cardboard covers and tied with a rope, is a unique piece in the publishing market that will soon have new news from this poet who travels through different readings to stop to write.

© 2016 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit