November 10, 1983, was a big day for Fred T. Korematsu and his legal team. Ten months after filing a legal petition on Fred’s behalf, they all finally stood before a judge in U.S. District Court in San Francisco. In 1942, Fred had been convicted of violating WWII exclusion orders for choosing to remain behind in California as other Japanese Americans reported for incarceration. And now, after carrying the burden of that conviction for over 40 years, Fred was back in court once again to challenge that conviction. Arguments were presented, and the room full of Nikkei spectators who waited tensely for the judge to give her ruling. They knew a victory would mean much more than Fred’s own cleared name. It would be a meaningful measure of vindication for the entire Japanese American community—legal recognition that the government had acted wrongfully when it incarcerated them from 1942–46.

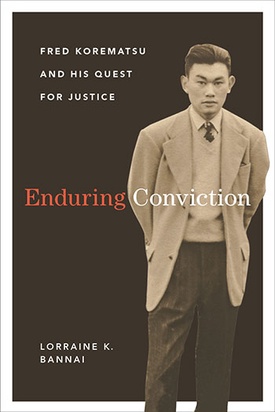

Lorraine Bannai was one member of the Fred’s young, mostly Sansei, legal team present in court that day, and this riveting first scene is the prologue to her new book, Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and His Quest for Justice. Today, she is the director of the Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality at the Seattle University School of Law.

Enduring Conviction is Bannai’s first book, and it was a long time coming. In a recent interview with this article’s author, she described how it came about after 32 years. The legal team had won the case, of course, and it was a landmark in the struggle for Japanese American redress.

“For many years after I worked on Fred’s case,” she said, “I and others on Fred’s legal team gave talks about his case and the lessons that we continue to learn from it. And at so many of these places, I was asked if someone was going to write a book about his story and our work on his case. I didn’t think I would be the one to do it, but I thought someone needed to.” And so eight years ago, when her law school provided her with the time and ability to take on the project, Bannai began the painstaking research process. The finished product is an exceptional contribution to the literature on Japanese American incarceration. It provides not only an inside look at the legacy of Fred Korematsu, but insightful commentary on how ideals of freedom and equality can diminish quickly in times of crisis.

An unassuming legal icon

Fred himself was an unassuming man. Born on January 30, 1919, he grew up surrounded by three brothers and his parents’ flower nursery in Oakland, California. Like many Nisei, his life was influenced by the American culture he grew up in, mixed with the Japanese culture and traditions of his parents. They attended Buddhist and then Christian church and flew koi streamers on Japanese Children’s Day. He was a Boy Scout and loved high school sports. And it was in spite of this West coast upbringing that Fred encountered racism at nearly every turn from a young age. He was routinely refused service at restaurants and barbershops, and even summarily dismissed from a welding job based on his ethnicity.

The racism rose to new heights following Pearl Harbor until February 19, 1942, when FDR signed Executive Order 9066. Japanese Americans could now legally be forced out of their homes and into camps surrounded by armed guards and barbed wire fences. The Korematsu family was ordered to leave their home and were moved into cramped barracks at the Tanforan race track in May, 1942. But Fred was not with them when they left. And this is where his legal journey began.

Rather than accompany his family to the buses that would take them to Tanforan, Fred chose to stay behind with his fiancé in San Leandro, California. He did nothing more, Bannai told me, than choose “to remain with the woman he loved in the place that had always been his home.”

And within the month he was arrested for violating the removal orders. Enter Ernest Besig and Wayne Collins, two Northern California ACLU lawyers bent on challenging the incarceration. Besig met with Fred in jail, and after warning him of their slim chances of success against a wartime U.S. government, Fred agreed to be a test case.

Fred’s decision to proceed with the case, Bannai tells us, was extraordinary. He may have been a soft-spoken welder with no college degree, but he knew that what was done to Japanese Americans was wrong. He knew that the legal case would be difficult. And he also knew that he would be almost completely alone in this fight. He would receive no support from his family. He was ostracized as a criminal by others in the Japanese American community while incarcerated at Tanforan and Topaz. The Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL) denounced those who sought to challenge the government’s actions, and the national ACLU leadership told Besig and Collins, Fred’s attorneys with the Northern California ACLU chapter, that they could not challenge Roosevelt’s authority to issue the wartime orders. In spite of all this, he chose to move forward with the case. They lost.

They lost first in the lower courts, then the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, and finally the U.S. Supreme Court. Despite Besig and Collins’ best efforts, a majority of the Supreme Court justices found that there was sufficient proof that the mass removal was justified by military necessity. The U.S. was at war with Japan, the Court explained, and there had not been enough time following Pearl Harbor to distinguish loyal from disloyal Japanese descendants. Hence, they had all been targeted for the sake of national security.

And that was it. The highest court had ruled, and Fred was left with a prison record for standing up against the incarceration.

It all turns around

Racial discrimination and his standing prison record plagued Fred after the end of the war. He worked jobs that would accept him with a criminal record, supported a wife and two children, served as events chair for the San Leandro Lions club, was active in his church, and attended his children’s school events. He always hoped that he could have one more go at his conviction, but he did not see a way to do it until one day in 1981, when he received an unexpected phone call. This was where it all turned around.

The caller was Professor Peter Irons from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Irons had visited the National Archives and Records Administration in Washington, DC to review cases concerning the incarceration, and found, to his astonishment, indisputable evidence of a government cover-up in Fred’s case file. That U.S. government had purposefully suppressed, altered, and destroyed evidence in order to engineer Supreme Court approval of the wartime incarceration. It was “a smoking gun,” Irons later said.

He flew out to California as soon as possible to present the news to Fred himself, and on meeting Peter, Fred immediately decided to reopen the case. Irons contacted lawyers already involved with the movement for Japanese American redress, and soon nine attorneys, including Bannai herself, had agreed to take on the pro bono case. For those on the legal team, Bannai told me, lack of payment meant little since “it was just an honor to be part of the much larger effort seeking to heal the wounds of the wartime incarceration.”

After months of work on the part of the legal team, Bannai herself filed the petition to clear Fred’s conviction. A victory would depend on the team’s ability to prove that a fundamental injustice had been done in Fred’s wartime case that had infected the final ruling.

“We all felt strongly that the evidence that the government presented the Supreme Court with a fraudulent record would justify the court reopening Fred’s 40-year-old case,” Bannai assured me in our interview. And as they soon found out, they were right.

Ten months later, on November 10, 1983, the team and Fred himself sat before Judge Marilyn Hall Patel of the U.S. District Court in San Francisco. The legal team had made public education surrounding the historical import of this case a priority from the very beginning, and while Collins had presented Fred’s case nearly friendless in 1944, now the room was packed with Nisei and Sansei spectators. So many organizations wanted to submit briefs supporting Fred’s cause that the judge felt compelled to ask that they coordinate their efforts and submit only five total, please.

And then Fred won. When the judge delivered a same-day ruling in his favor, the courtroom erupted in joy and tears. Fred’s conviction had been thrown out on the basis of recognition that the U.S. government had presented fraudulent evidence to support Japanese American incarceration during WWII.

“Nothing could restore the years taken away, the loss of opportunity, the loss of freedom,” Bannai remarked in our interview, “but judicial recognition is important. And for Fred, it was also important validation that he had done the right thing in choosing to remain when he was ordered to leave—he had been ostracized for refusing to comply and had lived with his criminal conviction for over 40 years. Those in the courtroom were overcome.”

Legacy

Fred Korematsu now stands as an American legal icon. He is remembered not only for his wartime stance, but also because, after winning his case in 1983, he went on to travel the country to speak about its importance. For the rest of his life, he reminded law students and public gatherings alike about the need to continue fighting for equality.

Bannai also reminds her readers throughout the book that Fred’s life and case serve as a warning of the suffering that can result from casting one group of people—any group at all—as foreign or dangerous based on generalized characteristics. Education is crucial, she says, to avoid scapegoating groups from Nikkei during WWII to Muslims today.

As a final question, I asked Bannai what individuals can do to preserve and advance Fred’s legacy; and naturally, the director of the Fred Korematsu Center for Law and Equality responded in no uncertain terms. “During World War II,” she said, “Japanese Americans stood virtually alone. Few spoke in their defense when the country turned against them. Today, we can all do our part to fight the similar targeting of other minorities. We can repost a story about the wartime incarceration or the unjust scapegoating of a community on Facebook; tell someone about a book or article or ask someone to go to a talk, film, or play about the issues; or support organizations that seek to preserve the story of the incarceration or advocate against intolerance. We can choose not to be silent.”

* * * * *

Lorraine Bannai will be at the Japanese American National Museum from 2 p.m.–3 p.m. on June 4, 2016 to discuss her book, Enduring Conviction. Q&A will follow.

© 2016 Kimiko Medlock