“Sundays became exciting during the summer. Baseball was not only fun, but it was a way of bonding with the other Nisei,” remembered Jerry Inouye, speaking about his baseball experiences in Portland, Oregon. In the 1930s and 1940s, Sunday baseball contributed to the heartbeat of the Nisei generation. Ballplayers of that era, though unheralded among mainstream baseball fans, proved their unyielding devotion to the game during some of the most difficult periods any American community has ever faced. Moreover, the game served as an important vehicle for recreation, community cohesion, and the boosting of morale.

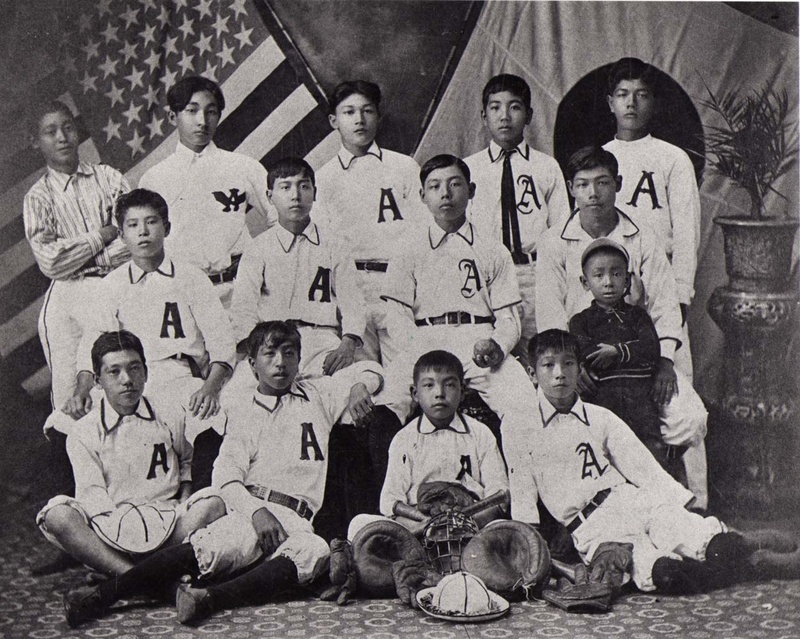

During the so-called “golden era” of Japanese American baseball, hundreds of Nisei clubs spanned the diamonds within large and small cities and farming communities, primarily in the American West, to compete for athletic and cultural honors. Wearing wool uniforms that bore such names as “Nippons,” “Asahis,” and even such major leagues inscriptions as “Dodgers” and “Giants,” teams playing games on well-manicured fields in the Los Angeles area, gravel pits in Hood River, Oregon, and within the orchards of central California, among other places, drew the attention of entire communities and fostered strong relationships among the players and the baseball aficionados. Some community members also saw baseball as another element in the advancement of acculturation within the American mainstream. And in the 1940s, Nisei baseball served as an important core for morale-building during the dark days of internment.

The game’s importance transcended the field of play. Games were sponsored by youth athletic clubs in the decades of the twentieth century, but by the 1930s churches, language schools, and even newspapers fostered team activity. Nonplayers often set up league schedules, organized statewide tournaments, and wrote sport columns in their community presses. Even incarceration did not deter the love of the game within the Japanese American enclave: they simply pooled their talents to build playing fields, construct equipment that included bats and backstops, and promote games. Moreover, they remained as competitive as they had been in earlier times. The “relocation centers” also exposed them to residents from varied regions, and through this experience ballplayers not only faced a different pool of athletes, but they learned that baseball was not exclusively a city or rural activity. In central California’s agrarian region, for instance, the national pastime had strong disciples.

During the first decade of the twentieth century, a group of Issei ventured to Livingston, a farming community that lies in the center of California’s agricultural-rich San Joaquin Valley. Led by Kyutaro Abiko, a San Francisco newspaper publisher and businessman, in 1904 they formed a settlement known as the Yamato Colony. Like so many of the contemporaries from other countries, these agrarians came with high hopes and an eagerness to do well in the “land of opportunity.”

As the Japanese established themselves on the North American mainland, they formed such organizations as the Japanese Association of America; founded in 1909, it took it upon itself to protect the general welfare of its constituents. At the local level, Buddhists and Christian church assemblies such as the Young Men’s Group, together with the educational society known as the Gakuen and the Kendo (the Japanese art of bamboo-stave fighting) Club sponsored many activities such as talent shows, picnics, and concerts. These types of communal events provided “emotional support,” according to historian Valerie Matsumoto. Furthermore, she claimed, they served to maintain “as much as they could of the Issei’s cultural heritage.”

Sport, of course, was also directly tied to the highly valued traditional samurai principles of courage and honor. “Stern visage, resoluteness in action, [and] physical toughness,” claimed writer John Whitney Hall, “…were the qualities most admired by the samurai class.” More importantly, the warrior “remained true to his calling and his sense of cultural identity as a Japanese.”

One Issei, Koko Kaji, spearheaded competitive sports, particularly baseball, in the Yamato Colony. Baseball, of course, was not unfamiliar to many of the Japanese migrants; indeed, America’s “national pastime” had planted its seeds in Japan during the late nineteenth century. Although there are varied interpretations as to the genesis of baseball in Japan, most chroniclers agree that it arose there in the late 1880s. However, at the outset, baseball aficionados could only be found among Japan’s urban elite, so historians reason that those who migrated to the United States probably learned the game during their Hawaiian stopover. Interestingly, Alexander Joy Cartwright, the father of America’s modern game, resided in Honolulu about the time Japanese migrants traveled eastward across the Pacific, many bound for the Americas. In any case, Kaji’s introduction to the game remains unclear. What is clear is that by the mid-1920s, “Smiling” Koko Kaji formed and managed the Livingston Peppers baseball team, a club that received considerable attention in the San Joaquin Valley.

As the second generation grew into young adulthood, many continued Kaji’s legacy by forming their own community-based teams. By the mid-1930s, Kaji’s Peppers had dissolved. However, prodded by their elders to do so, Nisei athletes organized another community team, the Livingston Dodgers. “By the time we got out of high school we developed our own sports activities,” recalled Fred Kishi, a local sports star in the region. Indeed, throughout the San Joaquin Valley, Nisei leaders formed amateur adult teams and eventually established baseball leagues; from 1934 to 1941. The Central Valley Japanese League consisted of eight teams. Churches and local merchants happily sponsored many of the teams. “We played against Walnut Grove, Lodi, and Stockton,” remembered Kishi. “These were all Nisei Leagues, and we played for probably about three or four years actively in this league. Most of the Nisei players developed their expertise playing in [these] games.” So great was their love of the sport that team members often assisted their mates on the farms to make time for baseball. “Every weekend we had the Livingston Dodgers,” said pitcher Gilbert Tanji, “so every Sunday when I had a hard time getting away, all the boys used to come and help me with certain work so I could take off Sunday early.”

Fred Kishi believed that the special chemistry came as a result of their upbringing. “The players on this team knew each other practically from the day we were born; we went to church together, we played on Saturdays together, and we went to high school together, so it just fell into place,” he pointed out. Coach Masao Hoshino, an Issei, stressed unity both on and off the field. Kishi remembered that Hoshino “had good psychological methods of getting us together. He made us go to Sunday school before we went to any games, so it was a very close-knit group that we had.” Former player Robert Ohki added, “The manager always use to say, ‘you guys got to go to church or we’re not going to play on Sunday.’”

Rivalries, of course, emerged to enliven the contests; among the most intense was the competition between the Livingston and nearby Cortez baseball teams. Like its counterpart in Livingston, a branch of the local Gakuen sponsored an organization called the Cortez Young People’s Club (CYPC). The CYPC organized cultural events, but by the late 1930s its primary interest turned to sports. Baseball was so popular that the Cortez players carved out their own baseball diamond amidst the vegetable fields. “We had a great big ballpark,” Yuk Yotsuya, former pitcher for the Cortez Wildcats, proudly claimed. “We were the only ones that had our own ballpark.” Yotsuya was a standout pitcher, who in one 1939 contest, came within one hit of pitching a perfect game against Lodi. Like the Livingston team, Cortez players also designed their work schedules so as to provide ample time for baseball. “We used to pick berries in the morning, then run to the game, and then we’d come back and finish the work,” remembered Yotsuya. Yotsuya’s teammate, Yeichi Sakaguchi, asserted, “We were obligated to the team…so we tried like heck to make [the games].” The Cortez team, in fact, was unique because its coach, Hilmar Blaine, was a Caucasian, a Shell Oil Company distributor who delivered gas to farmers in the Yamato Colony. Blaine, a baseball advocate, “helped us get started and then he helped us get uniforms,” remembered Yotsuya.

The fact that Cortez and Livingston were neighboring communities intensified the rivalry between many of the players. Indeed, many attended the same schools. We didn’t care who we won from [sic], just so we won from Cortez. We went to school with the Cortez boys and beat them, maybe 70 to 80 percent of the time,” claimed Gilbert Tanji. Yuk Yotsuya, whose competitive spirit still burned brightly a half century later remembered that the Dodgers were able to “practice more than we did. They [also] had a lot more material to pick from.” Indeed, between 1939 and 1941 the Livingston Dodgers compiled an impressive record of 34 wins and 3 loses.

America’s entry into World War II of course not only brought a temporary halt to Nisei community recreational activities, but also took them into one of the darkest chapters in American history. Confirmation that Japanese Americans were to be “relocated” came in February 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into action Executive Order 9066. Indeed, the announcement of the mandate drew mixed emotions from those affected. Some Nisei characterized their situation as a distinct sign of loyalty, because to oppose it, according to historian Roger Daniels, “…would merely add to the disloyal stereotype that already existed,” but under no circumstances did the eventual inmates believe that they posed a risk to the country’s national security. As low spirits understandably enveloped the American Japanese and community morale slipped, sport, it turned out, helped them endure their trauma and contributed to their sense of dignity. Consequently, athletic activities were embraced in an upbeat manner: indeed, through sport the Nisei and their elders came together during a period when cohesion was vital in this difficult period, baseball took center stage.

Along with the Livingston Dodgers and Cortez Wildcats, many players from communities well beyond the Stanislaus-Merced areas, such as Sebastopol, Walnut Grove, and Petaluma, for example, all ended up in the Merced “assembly center,” which eventually contained 4,453 residents. The organization of teams therefore, proved to be no problem. “Once we got into camp, everything fell into place,” remembered Fred Kishi. We had to get something going,” added Yeichi Sakaguchi. In fact, prior to their entry into the “evacuation center,” Masao Hoshina reminded his Livingston Dodgers to bring their uniforms and equipment with their other belongings. “We took our uniforms along with us, and we played at the Merced County Fairgrounds, which had a nice [baseball] stadium there,” claimed Kishi. “I’m telling you, the intensity of competition was very great and well organized.”

In an attempt to temper the trauma of incarceration, Gilbert Tanji optimistically viewed the temporary detention facility as an opportunity to face greater challenges on the baseball diamond. “We’d win so many games [at Livingston] that pretty soon nobody came to watch us play,” he recalled. “So when we got into camp there was more competition; it was more fun.”

“They had [games] going every day and we had a nice ballpark,” said Yuk Yotsuya. The grandstand was an attraction for both players and fans, particularly the elderly Issei who enjoyed sitting in the shade during the hot summer months. “They didn’t care who was played as long as they could watch the games,” stated Yotsuya. Games were constantly played at the fairgrounds, and one player remembered the competition was so intense that “several times we almost came to blows.”

At the Merced site, baseball captured much of the attention as 10 clubs vied for detention center “honors.” The baseball squads managed to complete up to 13 contests before “relocation” preparations forced them to postpone their “season.” In the fall of 1942, the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA) received orders to prepare the “evacuees” to more permanent sites; within a short time, the residents learned the whereabouts of their new “homes.” The 1943 baseball season, for the Livingston players and others at the center, commenced in southeastern Colorado, at a concentration camp called Amache.

Amache had relatively little in the way of sport facilities. There were no gymnasiums or baseball or softball diamonds, and only a grassless football field, while basketball and volleyball players endured dirt courts. “We had to make the baseball diamond, and there were no stands, no seats, no nothing, so the crowd just stood around the field and watched games,” remembered Fred Kishi. Gilbert Tanji recollected the fierce weather that sometimes intruded on the action. “A lot of times we had sandstorms, and sometimes we had to stop playing,” he said.

While the Dodgers excelled in the Amache softball circuit, they did not fare as well in the baseball league. Both the increase of talented opposition and the loss of key players due to work leaves or military obligations took a toll on the Livingston club. Playing as one of five teams in the baseball league, the Dodgers finished the 1943 season with a two and six record. Baseball, however, remained popular with the Amache inmates. All-star teams were regularly chosen, and, at times, they competed against clubs from outside their facility. In 1944, Amache baseball organizers selected an all-star squad to represent their “relocation center” in contests against a team at the Gila River, Arizona, camp. Confident that the West Coast paranoia of the Japanese had passed, the War Relocation Authority, after several weeks of debate, granted permission for the games to proceed.

*This article was originally published in More Than a Game: Sport in the Japanese American Community (2000).

© 2000 Japanese American National Museum