Why did they ‘choose’ to go to one of the ‘self supporting’ camps?

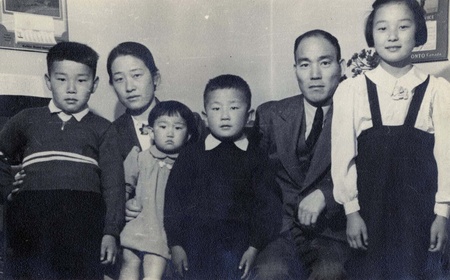

For parents and adult individuals, it was a trying time. The only consolation was that they were not alone. Close to 22,000 Japanese Canadians were leaving the West Coast. But for us children, it was no more than an adventure. My mother dressed us in our Sunday best as though we were going on a holiday trip. There were no casual blue jeans in those days. Minto Mines, our new destination, was a largely abandoned town with a few blocks of established homes remaining, which were quickly occupied by the early arrivals. Our home was one dragged in from outlying areas, likely formerly occupied by miners. Even so, I realized much later, that we were living in a house, larger than the government built shack such as in Tashme, where two families were forced to live in one.

Located in the Bridge River Valley, idyllically surrounded by mountains and a river, and soon after our arrival the land around our homes fenced and turned into vegetable gardens, my memories are those of a child, playing each day with friends and going to school (taught by educated members of our own community), well nurtured by both parents and community, even as they were suffering great upheavals to their lives. The Japanese Canadian population in Minto is recorded as numbered 322, so it was a small community.

I have memories of teachers like Mr. George Tamaki and Ms. Chizu Uchida, both of whom were, I realize now, not that much older than most of the students, but served us well as they continue to remain positively in my memories of Minto.

In such self-supporting sites, cost of transportation and rental fee of homes were paid by the residents, and so when work became available, my father took a job at a nearby sawmill to which workers were picked up and returned. Mothers tended the vegetable gardens, hoeing, and watering, and also canning and preserving the produce for the winter season, which was colder than what we were used to in Vancouver. Mothers learned from some grandmothers, and in our case, our next door neighbour Mrs. Nishi, how to make tofu, miso, and shoyu, and in fact, even amazake, sweet wine made from fermented rice. Her adult daughter, Nami-chan, taught my mother how to bake bread, and of course anpan (sweet bean filled buns), to be eaten on special occasions.

Minto was also the place where Mr. Morii chose to live. Through various writings, we have learned a lot about his role in both the early years in Vancouver (known as the owner of a gambling joint, an oyabun, or a `godfather’ sort of man, rumoured as having the police in his pocket). We also know that during the period before internment, he worked for the B.C. Security Commission to urge Japanese Canadians to cooperate in the internment process.

I knew him only as the man who built a wooden Shinto shrine on the slope of the mountain behind his home in Minto, o-daisan, I think it was called (not sure what that means). The other memory, more personal, is of a time when my baby sister became ill. My mother, who had a thick Japanese medical book that she always carried with her, having exhausted all remedies (including chopping earthworms and making a poultice which she applied to the sole of her feet to help reduce the fever), went to see him to request a doctor. There were no doctors in town and so one had to be brought in from a neighbouring town, or go there. I have no memory of what happened after this, but vividly remember that she had placed some money in an envelope to take to the o-daisan/Mr. Morii in requesting this favour.

So when and why did your family go to Winnipeg? How receptive was that city to JCs back then? (“Dispersal” and “repatriation”, 1945)

With the expiry of the War Measures Act, the government offered transitional powers in peacetime to the Dept. of Labour (St. Laurent), which led to two new policies: one of “dispersal” and the other “repatriation.” Of course, most of the interned were naturalized Canadians like my parents or Canadian born like myself who could not be ‘repatriated.’ In fact, we would be considered alien in Japan. Even though the war was ending and already Japanese Americans were returning to the West Coast, there was no third option for Japanese Canadians. Unlike the Americans, we had nothing to return ‘home’ to, as all personal properties left in care of the Custodian of Enemy Property had been sold in our absence.

My parents at first signed to ‘return’ to Japan, considering their daughter, our grandmother, and other relatives living there. In fact, my father, who had been living in Canada since his arrival at the age of nineteen, did not wish to leave. Canada had become his home. And, with news about hardships in post-war Japan, they withdrew their application and made the decision to go to Manitoba. My father had memories of living in Winnipeg, so had no fear of what many felt was an ‘unknown’ land to the east of the Rockies. Of course what was unknown was how Japanese Canadians would be treated in the east. Would it be the same as it was for them in racist Vancouver? What would be awaiting them? Most Eastern Canadians had little or no experience with Asian Canadians.

Under supervision of the RCMP (Royal Canadian Mounted Police), we left the internment camp of Minto Mines in around July of 1945. We travelled by train and stopped at Vernon to say goodbye to uncle Konosuke who had moved there in the previous year, working at the Chiba farm/orchard. He subsequently returned to Japan to his family. When we arrived at the Winnipeg railway station, members of the RCMP and the Security Commission were there to meet us and we were immediately taken to a vegetable farm, owned by a Mr. Ed Mancer, where my parents (who had never farmed before) were to work. And the first home given to us was a large barn.

My mother, in her memoir recounts this memory among others of her experience in Canada, particularly of the internment years, written in Japanese, during the last five years or so of her life. She describes her emotional response, saying:

a stove and a bed were brought in but the building, located in the middle of a farm, had a high ceiling and the walls inside were covered with tin sheets. Manure clinging on straw hung stuck to these walls. A bare light bulb hung from the high ceiling. I stood in the middle of this barn, which was to be home to our family of six, and couldn’t hold back the tears. But remembering our situation, I knew there was no choice but that this is how it is and will be for some time yet.

The farm where we were located was about a quarter of a mile from the town of Middlechurch, where in the fall we registered for school.

What do remember about my dad’s (Ibuki) family?

While I understand the Ibuki family worked in a sugar beet farm (of which I knew little about at that time), my parents worked in the vegetable farm owned by a Mr. Ed Mancer. I am now beginning to wonder if a sugar beet farm was also a part of Mr. Mancer’s farmland or if there was a neighbouring sugar beet farm. But I recall my parents were largely hoeing and picking berries. But I also recall that there was a family living within the same farmland in what I now recognize through documental photographs as a government built sugar beet workers’ shack. This was the Yasumatsu family. Kay Yasumatsu was a student in my class (which consisted of grades six, seven, and eight in one room).

I recall that Kay Yasumatsu and Norm Ibuki were in grade eight, and I was in grade six. At twelve years of age, I looked upon both Kay and Norm (who would have been fourteen) as much older. Even though we were in the same room, certainly there was a great difference in both appearance and thoughts between a twelve year old and a fourteen year old, so I had little contact with them.

Both Kay and Norm may have moved directly to this sugar beet farm site in 1942, and so may have already been attending this school since that time. But it was my first experience of a school outside of the internment site, so this was a traumatic experience for me to be among European Canadian students. Especially, too, that the teacher (I think his name was Mr. Bolton) mispronounced my Japanese name, Eiko, each time he referred to me, which added to this trauma.

My mother helped me to change my name to Grace, when I registered the following year in a school in Whitemouth where we had moved to.

We stayed in Middlechurch only for a year and moved to another rural town, Whitemouth, further east. We were still under restrictions, and could not yet move into the City. My father began commuting to Dryden, Ontario (returning home to us every other weekend). He found a job at a pulp and paper company where there were several Japanese Canadian men working.

Whitemouth was where I turned thirteen and where my brothers played hockey, and I learned to skate and also later to curl, as well, sing in the local United Church choir, and even join community friends at the town hall where I learned to square dance.

It was a small town with surrounding farms occupied mainly by German, Mennonite, and Ukrainian families. Five or six Japanese Canadian families had moved here during this ‘dispersal’ period. My father had rented the second floor of a large house owned by a Ukrainian couple, but later we moved to rooms behind a service station. No matter, even as we were treated kindly by the residents of this town, our lives were not normal in the sense that we lived behind a service station, furnished only with benches and table, no sofas or rugs on the floor. I was always beside my mother interpreting for her, while my father came home every second weekend from his work in Dryden, Ontario. We were, though treated with respect, still uninvited guests in this town still under the jurisdiction of the RCMP.

My recollections of this time is of a child, and it is only in retrospect, in listening to my parents talk about this time, and in reading my mother’s memoir, that I realize a whole lifetime had been destroyed for them, as there was no getting back to ‘normal.’ The struggle continued for many years after, even as the war ended, and restrictions were lifted.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki