“I believe art is about finding one’s place, the journey not limited by one’s own history, but about expanding one’s thoughts through sharing with others. It is, in my opinion, solely about living. Living and doing without necessarily having to consciously interpret, define, or choose.”

—Vancouver art curator, historian, and educator Grace Eiko Thomson

When Hamilton art curator Bryce Kanbara announced that there was going to be an artists symposium in April, it was with some enthusiasm that I learned about it: “Surely, if there was a group of Japanese Canadians who would be connected to learning about the possibilities of who and what they are, it would be artists.”

As a middle-aged Sansei, one of the things that has always irked me about the Japanese Canadian (JC) community is that it seemed to end in 1988 with that redress letter of apology and cheque. While most other ethnic groups seem to educate their members about their history, honouring heroes and role models, we seem firmly stuck in 1988.

While I have not actually met curator Grace Eiko Thomson (nee Nishikihama) yet, I was delighted to learn that she knew my father’s family as hers was “relocated” to a farm owned by the same fellow who had the beet farm where my dad’s family “worked” during World War Two.

One of the benefits of seeking out truths for oneself is that there are moments of revelation when one least expects them. In the preceding interview, Grace tells me bits about my own family history during the Manitoba years that dad still doesn’t talk much about at 85.

Can you begin then by talking a bit about your own family’s immigrant history?

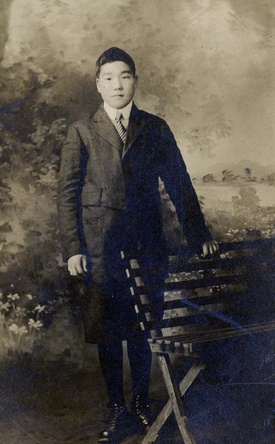

My father Taguchi Torasaburo was born in Mio mura (village), of Wakayama ken (prefecture). Upon finishing his school years, at age nineteen, he arrived in Canada in 1921, eager to join his older brothers, Katsutaro and Konosuke, who had with their father come to Canada earlier, perhaps at first out of curiosity. Their father, Taguchi Torakichi, subsequently returned to Japan.

They had like many other men who came from this village, been encouraged by Kuno Gihei, who had delivered to his fellow countrymen, the message of a great abundance of fish in the West Coast of British Columbia. It is said that Mio mura was emptied of its men, so that in time it came to be referred to as “Amerika mura” as residents became somewhat Westernized in clothing and in language and in their affiliation with the new world.

Upon his arrival, however, my father was told to take another path, to learn to speak English. Likely the older brothers saw not having the language a handicap. So after picking up basics working as a house boy, which was the way to go in those days, he began working on railway passenger cars between Vancouver and as far east as Moose Jaw (Saskatchewan) and Winnipeg.

According to family documents, he is registered as a naturalized Canadian, December 1929, under the name of Nishikihama, not Taguchi. My father and his brother Konosuke, being third and second sons respectively of the Taguchi family, were adopted in adulthood by two Nishikihama families, related to them. This traditional practice is known as yoshi1. As a result, both my father and his brother Konosuke changed their surname from Taguchi to Nishikihama, each now owning a home in Japan, even as they worked and lived in Canada.

In the following year, my father Torasaburo was called back home to Japan by his parents to an arranged marriage.

My mother’s parents were Fukumatsu and Ei Yamamoto of Mio mura. The father’s story is an interesting one. As a younger son, he was sent to a neighbour village to marry a daughter (a yoshi arrangement) of a miso factory owner, whose father had died. Instead, the widow took Fukumatsu as her own husband. In time, the story as my mother tells me, Fukumatsu tired of this way of life, kicked aside the miso bucket, walked to Yokohama harbour, and got himself hired as a carpenter on a ship bound for Canada.

I know little else about him except that not many years ago, I found his name in a book, published in Japanese in 1935 by Steveston’s Japanese Fishermen’s Benevolent Society (Dantai), dedicated to the second generation, about the struggles of the early immigrants to this area. Fukumatsu Yamamoto is listed as a member of this Society in the year 1895. He had two sons with his wife when he left for Canada, and a few years later, while he was working as a fisherman, the two sons arrived to join him. Likely their mother had died. And so he put the two sons to work and returned to Japan, where he remarried. My mother Sawae is the second of three daughters of the second marriage.

What was your family situation at the time of the evacuation and internment?

My older sister Kikuko was born in Steveston’s Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital2 on November 20, 1931. I was born in the same hospital two years later and my parents, by the mid-‘30s, made the decision to move into the City of Vancouver, residing firstly at 522 Powell Street. Before the birth of their third child, a son Toyoaki, we had moved to 510 Alexander Street.

My father had been hired as a buyer for a Codfish Cooperative Society, its offices located at a dock not far from where we lived. I remember my father walking to work in the mornings, dressed in a three piece suit, fedora, and spats over his shoes (traditional men’s wear in those days). On weekends, I remember my father taking us children to the dock, and each of being weighed on the large fish scale. Also, that on New Year’s Day, his boss Mr. Templeton (I think his name was) coming to our home for a drink.

I learned more recently that the Codfish Cooperative was one of the earliest fishing industry cooperatives, run by Aboriginal, Caucasian, and Japanese fishermen. I have, so far, not been able to learn anything more than that. Interestingly, my mother was familiar with names of the various islands along the West Coast and learned in asking about this knowledge that she used to help my father write his annual reports.

My mother, a daughter of someone who had made some money and returned to Japan, had privileges in her life before arriving in Canada. For instance, after finishing her schooling locally, she was sent to Wakayama City, where she continued her studies essentially women’s studies in preparation for a good marriage. She took such courses as flower arranging, tea ceremony, literature, and sewing.

My own experience of my mother is of someone who loved reading, writing poetry, and of an excellent seamstress. She had continued to study sewing design in Vancouver and even during internment. I have several photos of myself dressed in beautiful gowns, which she had designed for me to wear to Christmas balls held by the Japanese Canadian community annually in Winnipeg and to proms invited by university students who were studying at University of Manitoba, one of the first universities to open to Japanese Canadian students, after internment.

My memory of my mother is of someone who had a lot of anger buried inside her. Marrying someone who lived in ‘Amerika’ was supposed to have offered a privileged life in the new world, and though Japanese immigrants faced a lot of discrimination, living in Powell Gai (‘Powell Town,’ as the residents called it) where all amenities were available, and not having English language was not a problem, and my father landing a good job, their life had started out well. There was much to look forward to as children were born.

In any event, that was not to continue, as their lives were totally disrupted in 1942. I had graduated from Japanese United Church kindergarten, and was in grade two at Lord Strathcona Elementary School, as well, attending Japanese Language School.

My mother was twenty-nine years of age; my father thirty-nine. They had five children, newborn to nine years of age. My older sister was visiting grandmother in Japan, and she was not to be reunited with us until she was 18 years of age, when she returned to us in Winnipeg after restrictions were finally lifted.

What kind of impact did it have on your parents and siblings?

I’m sure for most immigrant families making a choice of where to go during internment was not an easy one being forced to leave their past lives, abandoning all personal possessions.

When the Order-in-Council PC 365 was passed by the Government of Canada which designated an area 100 mile inland from the West Coast as a “protected area”, and when Order-in-Council PC 1486 was passed on February 24, 1942, which authorized removal of all “persons of Japanese racial origin” and gave the RCMP power to search without warrant, enforce a dusk-to-dawn curfew, and to confiscate cars, radios, cameras, and firearms, my parents were expecting their fifth child.

Since my mother was expecting, and my uncle Konosuke (Kono-ojisan) was living alone in Steveston, his family living in Japan at that time, decision was made for our family to leave Vancouver and join him in Steveston where decision regarding our `relocation’ may be made together. My baby sister was born at the Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital, located next door to my uncle’s home in Steveston, on March 1st, 1942.

As a child, of course, I did not know what was happening. As we packed to leave, and as I bade goodbye to my friends at Lord Strathcona Elementary School, I remember my mother saying not to worry that we will be back soon. We could not know, at that time, the extent to which our lives would change into the future.

Decision was made mainly by my uncle, talking with his fishermen friends in Steveston, to go to a self-supporting site of Minto Mines (a lost gold mine town). Father commuted to Vancouver daily to his workplace while decisions were being made.

Before leaving, I remember helping my mother pack several boxes in which she put away all her treasures, of dishes and potteries, ornaments and special sets of Japanese dolls which celebrated the annual boys’ and girls’ festivals, some kimono which she had brought from Japan, books she cherished, etc. The boxes were sealed and put into the shed, behind my uncle’s home, then carefully locked. Of course, within days of our leaving, everything families had carefully left behind in their homes were vandalized and stolen, some objects sold at auctions, we were told. Few items were returned to the community.

Family members were allowed to take only few necessary items to the internment sites, with all personal properties, homes, businesses, fishing boats, cars, farmlands, etc., left in the care of the Custodian of Enemy Property expected to be returned to us at the end of the war. We learned that within a year, all personal properties left were being confiscated and sold by the government, without consent of the owners, with a fraction of their value compensated to the owners, thus internees were paying for the cost of their own confinement.

Note:

1. A family without a son adopts a relative’s younger son, or adopt a young man from another family to marry their daughter, to keep ownership of property under the family name.

2. The story of establishment of the Japanese Fishermen’s Hospital is told in the book published by the Benevolent Society in 1935.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki