The Gardena Valley Gardeners Association (GVGA), once an influential force in the South Bay, will officially disband at the end of 2015.

The GVGA came full circle as it held its last official meeting in November, at the same location where it had held its first official meeting—at the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Institute (JCI).

Back in the summer of 1955, however, when the GVGA first officially met with approximately 60 people, the JCI was still known as the Gardena Valley Japanese Community Center.

The decision to disband was not a difficult one. “Nobody comes to the meetings,” said Bill Toru Nishimura, 95, the only charter member still active with the GVGA.

The GVGA, at its peak during the late 1960s and early 1970s, numbered about 465 paid members, with estimates as high as a total of 800 paid/unpaid supporters and gardeners who came out to various GVGA educational and social activities.

“Today, we only have 102 members,” said George Kamio, a two-term GVGA president (1987–88) and current treasurer.

In addition to Nishimura and Kamio, Joe Watari has been the third regular meeting attendee, although Watari is an architect by profession.

“I’m just an add-on,” joked Watari, who has been supporting GVGA activities for close to 35 years. “My dad and brother were gardeners.”

THE BEGINNING

Although the GVGA record of past presidents lists Paul Koga as the first president, Nishimura said Koga only presided over a few GVGA meetings before becoming president of the Southern California Gardeners’ Federation, so he considers Hideo Hiraga, listed as the second GVGA president, as the real first GVGA president.

It was no coincidence that the GVGA formed in July 1955, the same month and year as the formation of the Southern California Japanese American Gardeners League, which was renamed the Southern California Gardeners’ Federation a year later in 1956.

Also in 1955, other gardeners’ groups were established in Southern California: Bay Cities Gardeners Association, Crown City Gardeners Association (formerly Gardeners Association of the Pasadena Area), East San Gabriel Valley Gardeners Association, Hollywood Gardeners Association, Los Angeles Southwest Gardeners Association, Los Angeles Uptown Gardeners Association, Orange County Gardeners Association, Riverside Gardeners Association, and San Fernando Valley Landscape Gardeners Association.

The impetus that rallied gardeners together in 1955 was the introduction of California Assembly Bill 1671, also known as the Maloney Bill, named after sponsor Assemblyman Thomas Maloney.

If passed, AB 1671 would require all maintenance gardeners to be licensed by the state.

Nishimura recalled that Nisei, like himself, initially supported AB 1671. “We thought this was a good idea to protect our business, because there was a grandfather clause that said if you were gardening before the bill passed, you automatically got a license.

“But then the Issei questioned us. They said, ‘What are you guys thinking? There are many people coming to the United States from Japan. When they come here, they first have to learn English and then take the test and then get their license. You want them to go through all that misery?’”

The debate over AB 1671 spread statewide, with the split mostly along language lines as Issei and Kibei gardeners opposed the bill and younger Nisei supported it. But an Issei-led education campaign won over bill supporters, and AB 1671 was soundly defeated.

THE UNION

The gardeners had little time to rest on their laurels. In 1956, Local 399 of the Building and Service Employee International Union, AFL, launched a second drive to unionize the gardeners.

The first aggressive campaign had occurred in 1949, with the gardeners having to concede and join Local 399 after it got the support of Teamsters Local 396, which held contracts with a large majority of Los Angeles-area rubbish and disposal operators, which, in turn, controlled trucking services. This hampered the gardeners, who needed to dispose of their green waste.

The gardeners agreed to join Local 399 on certain conditions but when the union failed to honor these stipulations, many gardeners left the membership by the mid-1950s.

Because Nishimura had not started gardening until 1952, he missed this first campaign, but he was witness to the second aggressive membership drive by Local 399.

“Whenever we took our trash to the dump, they (union men) would come up to us and tell us to join the union,” recalled Nishimura. “Sometimes when you’re parked on the curb, they would park really close to you so you can’t get out. They were really pushy.

“But there wasn’t any gain for us by joining that kind of a union. They weren’t going to give us any new customers. They just wanted our money, so we opposed joining that union.”

Nishimura recalled attending federation meetings in Little Tokyo where attendees were educated on various union tactics. He recalled hearing one story where a gardener had to call a tow truck because unknown drivers had parked a car in front of and in back of his truck and the drivers were nowhere in sight.

“Anna koto shiyotta no yo (they used to do those kinds of things). To harass us,” said Nishimura.

But the newly politicized and organized federation successfully fought back, forcing the union to withdraw. The federation also formally incorporated, retained legal counsel, and in 1957 helped umbrella associations such as GVGA adopt a medical insurance program, a popular program to this day.

EXPANSION

As GVGA matured as an organization, it became more active. In May 1960, it started a Mutual Aid and Welfare Program, which offered up to $500 to members who needed emergency assistance. Enrollment was $15 per year.

In November 1960, GVGA organized the fourth annual California Landscape Gardeners’ Convention at the Statler Hilton Hotel in downtown Los Angeles, where a record 1,200 people from across the state attended.

The GVGA invited the Gardena mayor to the convention, and he was so impressed by the convention that he later approached GVGA about becoming involved in a beautification program for the City of Gardena.

Thus in 1961, the GVGA undertook their first major project—creating the Issei Japanese Garden, which can still be seen on the north side of 162nd Street, in front of the current Human Services Division parking lot.

Nishimura said an expert designed the pond so that the sound of the water would echo just right, but the pond did not last long.

“That was our first major project,” said Nishimura. “The rocks and plants are still there but we had to destroy the pond because the kids were monkeying around in the water.”

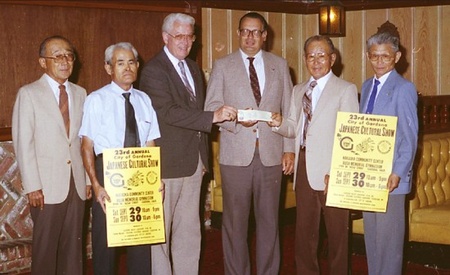

CULTURAL SHOW

With the success of the Issei Japanese Garden, GVGA members and the city discussed hosting a landscape show.

The inaugural Miniature Landscaping Show, renamed in 1968 to the Gardena Valley Japanese Cultural Show, was presented in December 1961 at the Gardena Valley Community Center, which was razed in the 1970s to make way for the Human Services Division parking lot.

According to Nishimura, the early Miniature Landscaping Show was spearheaded by the likes of Kay and his wife Ruby Iizuka, Nick Katsuki, and Frank Okada.

Nishimura recalled that the first show was small but attracted attention, and soon many Nikkei community organizations came out to support it.

“Credit really should go to the community,” said Nishimura. “The community really got together and supported this event. It was groups like the bonsai, shodo, judo, kendo, ikebana, and others that really got together and helped us.”

After the Gardena Valley Community Center was razed, the GVGA-sponsored cultural show was moved across the street, to the current Ken Nakaoka Center.

Nishimura said Eddie Takemoto spearheaded the making of the torii, a Japanese traditional gate, which welcomed visitors to the cultural show.

“Eddie Takemoto was really talented,” said Nishimura. “He designed the torii, and we helped built it. You can take it apart because the parts were inserts. And we used to loan the torii to other groups.”

The GVGA sponsored the last cultural show in 1996, not due to lack of interest, but because of a manpower shortage, since it was becoming harder for the aging gardeners to perform the physical labor. Tsuneyoshi “T” Kobayashi and Katsumi Nakamura were credited for making the cultural show a success towards the tail end of its existence.

By 1996, close to two dozen local Nikkei community organizations were involved, ranging from chado (tea ceremony), temari (colorful thread entwining), and bunka shishu (needlework) to kendo, judo, and naginata.

Nishimura recalled one show where a koi jumped out of the koi exhibit pool and almost died.

Since its inception in 1961, the GVGA also donated portions of their net proceeds to the Gardena City Beautification Fund. By 1996, GVGA had donated approximately $45,000 from the cultural show to the fund.

With this fund, the city purchased and planted trees in the Civic Center area; installed a sign at the old community center; purchased and placed “Welcome Gardena” signs throughout the city; and purchased and planted 25 trees on the northeast section of Rowley Park.

In addition, $5,400 from the fund was used to help defray costs to landscape a new City Hall complex, the Nakaoka Memorial Center, and the Rush Memorial Gymnasium during the 1970s.

LIBRARY

In October 1964, the GVGA constructed the Japanese Garden in the interior court of the Los Angeles County Public Library, Gardena Branch, also known as the Mayme Dear Library.

“Los Angeles (County) Supervisor Kenny Hahn approached us about making a garden,” recalled Nishimura. “Kenny Hahn was the county representative for our area.”

The GVGA donated close to 2,700 volunteer hours and brought worldwide attention to the City of Gardena after the garden was awarded the Blue Ribbon of Excellence in Design by the Society of American Registered Architects.

“I remember a few of the GVGA members flew out to Washington, D.C. to personally receive the award from (First Lady) Nancy Reagan,” said Nishimura.

The garden was designed by Takuma Tono, an internationally renowned professor of landscape architecture at Tokyo Agriculture University. Yoshio Konagi of Ichikawa, Gardena’s sister city, donated a toro or stone lantern, which had been in his family for 150 years.

At the January 1969 installation banquet, Hahn honored the GVGA with the presentation of the Los Angeles County and the U.S. flags. A California flag was presented to GVGA by Assemblyman Larry Townsend’s wife on behalf of the assemblyman.

Another big GVGA supporter was California Sen. Ralph C. Dills.

BUILDING PURCHASE

During the early years, the GVGA continued to meet at the Gardena Valley Japanese Community Center, which was re-chartered as the Gardena Valley Japanese Language School in 1967 and a year later, as the Japanese Cultural Institute.

The history of the JCI property ownership is complex, and for purposes of this article, it will be simplified to say that it involved the Moneta Gakuen, Gardena Gakuen, and Compton Gakuen coming together after World War II to offer Japanese language classes and a community meeting space at the current JCI site.

Nishimura recalled that when the Nisei veterans wanted to build the current Veterans Hall on the JCI site, “they had enough money for the building but not enough money to purchase the property, so they approached all the big organizations meeting at the center for permission to use the land.”

“Ken Nakaoka came to our GVGA meeting and asked for our permission because that land was owned by the (Nikkei) community,” recalled Nishimura. “They proposed that if they could build their own structure on this community land, then they would switch the ownership of the building to JCI after 20 years.”

But by the late 1960s, GVGA estimated close to 800 paid/unpaid members, so they made the decision to purchase their own building on Western Avenue in 1969. The building was donated to Keiro in the late 2000s, and shortly thereafter, sold off by Keiro.

CSUDH

In 1978, Dr. Donald Hata, then a history professor at CSU Dominguez Hills, approached GVGA about constructing a Japanese garden on campus to symbolize the value Nikkei gardeners’ placed on higher education. Hata had become aware of the gardeners’ contributions when he served as Gardena city councilman.

Hata recalled that the gardeners gave up their Sundays—their only free day—for eight months to create the Shinwa-En or Friendship Garden, designed by landscape architect Haruo Yamashiro.

Hata, along with his late wife, Nadine Ishitani Hata, would also come out on their Sundays to support the gardeners.

When the gardeners made a special trip just north of Oxnard to bring back boulders for the garden, the Hatas came along.

“Don helped us with the rock hauling and Nadine was the camera person,” recalled Nishimura. “Nadine really documented everything we did that day. It was a big deal because we loaded those boulders with a fork lift.”

In addition to the GVGA, other volunteers included the Pacific Coast and Los Angeles chapters of the California Landscape Contractors’ Association (CLCA) and the Centinela Chapter of the California Association of Nurserymen.

In 2009, CSU Dominguez Hills held a rededication ceremony after the garden was restored by volunteers of the Pacific Coast Chapter of the CLCA.

During the restoration of the tea house, architect Watari added a performance deck where programs could be staged.

OTHER PROJECTS

In 1961, the GVGA initiated a blood bank program for its members, through which more than 100 gallons of blood had been donated over the years before it was discontinued in the mid-1990s.

In April 1964, the GVGA started publishing the Gardeners’ Association Press or GA Press, a bilingual 16-page publication, but by the 1990s, it had dwindled to two pages of Japanese and two pages of English.

The GVGA unofficially also landscaped two-and-a-half acres of the Torrance Memorial Hospital.

“This wasn’t an official GVGA project,” said Nishimura. “This was more as a Friends of Torrance, where GVGA members and landscapers and nursery people donated plants and their time. It was a quick, one day job.

“The garden is gone now. It was destroyed when the hospital made an extension.”

In April 1976, the GVGA landscaped the JCI garden.

During the 1970s, the GVGA continued to remain politically active and successfully petitioned to have business license fees reduced in the cities of Gardena and Carson.

They also held classes on pest control to help members pass the test for the State Agricultural Pest Control Operators License.

Later, when the City of Los Angeles waged almost a decade-long battle to pass a leaf blower ban bill, GVGA members supported the federation in successfully opposing the bill.

When the 1984 Olympic Games were held in Los Angeles, GVGA volunteers re-landscaped the County Library in Carson, near the Velodrome (later replaced/renamed the Home Depot Center, StubHub Center, and VELO Sports Center), where Olympic bicycling events were held.

In 1991, the GVGA re-landscaped the Shibusa Garden at Peary Middle School, but that garden has also fallen under neglect.

“That garden is all gone now because no one took care of it, but I think there are still remnants of the torii, maybe the two posts,” said Nishimura.

During the late 1990s, the GVGA landscaped the Gardena-Carson Family YMCA, which took six months.

“We had a huge area to landscape, but now, most of it is a parking lot,” said Nishimura. “But at that time, we all received a plaque from the YMCA.”

For many years, GVGA volunteers also provided regular maintenance landscaping to the South Bay Keiro facility and Gardena Buddhist Church.

Today, GVGA contributions in the South Bay can still be seen, but development interests continue to pave over green space and the changing demographics of Gardena have led to fewer people knowledgeable about maintaining a Japanese garden. It remains to be seen if the surviving GVGA-initiated gardens will outlast the last of the Nikkei gardeners.

(Sources: Interview with George Kamio, Bill Nishimura, Joe Watari; past GVGA programs/brochures; GVJCI 100th Anniversary program book; “GreenMakers: Japanese American Gardeners in Southern California,” edited by Naomi Hirahara)

* This article was originally published on The Rafu Shimpo on January 5, 2016.

© 2016 Martha Nakagawa / The Rafu Shimpo