A symposium on "No-No Boy" will be held at the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Washington in Seattle on March 12. Researchers will discuss the issues behind the novel, such as the meaning of the question about loyalty to the United States that was asked when Japanese Americans were placed in internment camps during World War II, and the reaction of the Japanese American community.

The symposium is being held as part of a program at the University of California, Los Angeles' Asian American Studies Department, and it is clear that the world symbolized by "No-No Boy" is not limited to literature, but is still a topic of ongoing discussion. This is probably why this novel continues to be read.

Following in Okada's footsteps

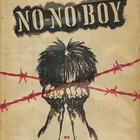

John Okada's "No-No Boy" was republished by a young Asian American in 1976, 19 years after its first edition, which went unmentioned and forgotten. The University of Washington Press later took over as publisher and continued to publish the book.

The first edition in 1957 consisted of just the novel itself, but for the reprint, a preface and afterword were added. It may seem unusual to have a preface for a novel, but they express the passion of the young Japanese-American and Chinese-Americans who were passionately involved in the reprinting. They also describe the episodes that led to the reprinting.

The preface was written by Lawson Inada, a third-generation Japanese-American poet. Inada describes how he and his friends were shocked by the work of John Okada and how he tried to spread the word about it, how he tried to track down Okada's family, about which there was no information at the time, and how he and his friends traveled from San Francisco to Los Angeles to visit Okada's widow, Dorothy, and how he met Dorothy and asked her about Okada and the No-No Boy.

Dorothy tells Inada and the others, "You two are the first people to come and see John about a book." They then learn that John had written a book about the Issei, but after he passed away, they tried to negotiate about the book but got no response from anyone, so they burned it and disposed of it when they moved.

Inada said that he was proud and pleased to republish Okada's book and send it out to the world, praising his achievement of opening up a new era as an Asian American writer. There is no criteria for whether the book will sell or not, and one can sense the growing pure desire to deliver a valuable book to as many people as possible.

Finally, he praises No-No Boy for being more than just great, timeless art.

Were the remaining manuscripts burned?

The afterword was written by Chinese-American playwright Frank Chin, whose play "The Chicken Coop Chinaman" was also produced in a accredited theater in New York, the first time that an Asian-American writer had done so.

In the afterword titled "Searching for John Okada," Okada speaks from the perspective of a fellow Asian American writer about his desire to see non-white cultures in America spoken about and literature emerge, and pours out his passionate thoughts about the significance of "No-No Boy," as if it were the birth of a long-awaited Asian American.

Frank Chin's words can also be interpreted as Okada's work providing an answer to the identity crisis that has forced us to continue asking ourselves who we are.

Regretting not having met Okada while he was alive, Chin visits Seattle, where "No No Boy" was set, and then meets Dorothy in Los Angeles with Inada. There is very little information available about Okada, who passed away leaving behind only his debut work, which was little known to the public, so he tries to get closer to him.

However, when Dorothy told him that she had tried to donate Okada's manuscripts, notebooks, and other writings to the UCLA Japanese American Studies Project but was turned down, so she burned them all, he frankly expressed his frustration and anger at the time, saying, "I wanted to hit Dorothy" and "I wanted to set UCLA on fire."

But what was left behind was not entirely empty: a modest profile Okada wrote about himself, which is presented here.

"The only great writer"

There is another story as to how the remaining manuscripts and other materials were disposed of, but I will introduce that at another opportunity. Chin then visits Seattle again, where he finally meets John Okada's brothers and father and learns about Okada's character and life.

He also meets Doris Mitchell, his boss at the library where Okada worked while he lived in Seattle and with whom he remained friends even after he left Seattle, and she shares her memories and details about Okada.

The afterword, which includes these things, allows the reader to get a sense of Okada's character and, at the same time, the passion of Inada and Chin, who revived forgotten writers and their works. At the end of the afterword, Chin states that Seattle is a special city that has given birth to Asian American journalists and writers (James Sakamoto, Monica Sonne, Bill Hosokawa, Jim Yoshida), and then makes the following powerful statement:

"John Okada is the only great writer"

© 2016 Ryusuke Kawai