The Upcoming Exhibition

How East met West in photography is revealed in an upcoming exhibition at the Japanese American National Museum (JANM). Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940 will be on view from February 28 to June 26, 2016. The exhibition contains 103 prints that include still life, landscape, portraiture, along with more experimental abstractions. The images were obtained from the families of the photographers, private collections, and public institutions. Many of the photographs are appearing in public for the first time. On display will be a variety of publications that have included some of the exhibited photos over the years. Visitors will see the cameras that were owned and used by three of the photographers and a trophy won by one of the others. Videos will feature interviews with the children of some of the exhibited photographers and the images of their families.

It has been 30 years since the first comprehensive exhibition of Japanese American photography. Dennis Reed, who is Professor Emeritus of Art at Los Angeles Valley College, curated the original show, as well as the current JANM exhibition. Professor Reed would like to see this exhibition eventually travel nationwide. He has devoted 35 years to Japanese American photography, and hopes that his small inner circle of colleagues will continue to expand.

The public is encouraged to see this exhibition and use this article as a guide. For those who cannot arrange a visit, this article provides some direction for home study.

Spiritual Design in the Decorative and Fine Arts

In 1853, U.S. naval commander, Matthew Perry, reestablished trade and discourse between Japan and the outside world after two centuries of Japan’s sakoku, or a period of national isolation. Suddenly, Westerners discovered anew Japanese arts and crafts, which they found appealing in many ways.

Decorative art, consisting of functional everyday objects, produced with a variety of materials like ceramics, lacquerware, and textiles, often showed the same level of mastery and diligence as fine arts like painting and sculpture. Typically, Japanese artists did not seek to copy the physical world as precisely as Westerners. Rather, Japanese artists crystallized, more profoundly, a grand design underlying what they considered to be superficial outward appearances.

When European Impressionist painters later began in the 1870s to capture changes in lighting, moment to moment, Japanese painters continued their own tradition of depicting more abiding patterns like the cyclical change that is perceptible in the seasons of the year and monthly phases of the moon. Such motifs were found, for example, on Japanese scrolls and screens. With each passing, there was sadness, what the Japanese called “the pathos of things.” But it was balanced with expectation of return and renewal, as when cherry blossoms reappear each spring. It was a refreshing contrast to the wilted flowers and skulls common in Western still life paintings that signified fleeting beauty, inexorably leading to death, a strident message that all vanity is folly.

The Japanese outlook conferred immortality upon everything—animate and non-living. Nothing was insignificant. By the same token, nothing dominated. Human beings were connected to everything else. In Japanese art, humans are given our rightful, modest place in the universe. Human faces tend not be highly individualized. Human torsos are shaped and posed to blend into an overall design, the scheme of things.

Natural beauty, in its simplest forms, manifests an order to the universe, which Japanese artists capture delicately, often through abstraction, whether it is a woodblock print, a haiku verse, a tea ceremony, or a floral arrangement (Dennis Reed, 1988). This Japanese fidelity to design made their arts and crafts decorative in the eyes of Westerners, whether or not the spiritual dimension was being recognized. Of particular interest to Western painters were the Japanese woodblock prints, or ukiyo-e. Typically, the prints had vivid colors and broad geometric forms.

A more profound aspect was striking negative space typically appearing as a void between physical objects. It conforms to the Japanese notion of a vacuum that cannot last, just like a promise that cannot remain unfulfilled. A traditional Japanese bow pauses just before the torso returns to an erect position, in order to accentuate the show of respect. With silent interruptions, the performing arts and ceremonies both provide moments for reflection, a clearing of the mind before summoning the creative energy necessary to handle dramatic tension. In Japanese decorative art, life need not be explicitly depicted. Incidental detail like texture and shading of objects is often left out. Even whole objects—or just parts of them—can be omitted.

More important than the details is the harmony and balance in nature, which is reflected in Japanese decorative art by connecting elements. For example, the foreground and background can be brought closer together by flattening the picture through a reduction or omission of linear perspective. Western painters were so fascinated by Japanese art that they borrowed decorative elements. Influence also flowed in the opposite direction.

Photography Imitating Art

The cultural exchange that enriched painting also happened in photography. This story is unfamiliar to most laypersons, who tend to consider photography intrinsically realistic, always expecting photography to replicate the visual world in every detail, while failing to see the poetic and decorative potential of photography. Most people do not realize that Japanese American (Nikkei) photographers and even some of their White counterparts in the U.S. and abroad (including some prominent Photo-Secessionists like Edward Steichen, George Seeley, and Clarence White) abandoned full-fledged realism, and adopted a more pictorial, even painterly approach, more in line with Japanese tradition. Pictorialism prominently featured a dreamy, soft focus, created with suitably designed lenses and elaborate printing processes.

Like decorative painting, pictorial photography looked uncluttered. An entire picture might even include just one geometrically interesting object. A scene was often reduced to its essentials. Part of an object could suggest the whole. A viewer could be drawn into the push-pull among objects, and ignore any asymmetry of composition.

Pictorial photography by Japanese Americans reduced or eliminated linear perspective by pointing the camera downward or, even more drastically, limiting the field to a backdrop that was a flat surface like a wall. If desiring some depth, a photographer could resort to aerial perspective, consisting of overlapping shapes, often hills and mountains, which become lighter in tone as they recede in space.

Additional design elements appear in one particular photograph of Mount Rainier outside Seattle, which resembles Japanese paintings of their country’s iconic Mt. Fuji. The scene is titled, The Mountain That Was God, photographed by Iwao Matsushita. The pointed crest of a lone pine tree, mystically set apart as a silhouette in the foreground, directs our attention to a sunlit peak in the background. The tree is more than just an accent that is made conspicuous through asymmetry. Rising above the abundant mist in the photograph, characteristic of the Pacific Northwest and Japanese forests, the radiant crown of Mt. Rainier is heavenly. Large bold shadows that dramatically contrast with the light are much more than just decorative negative space.

Collection of the Uyeda family.

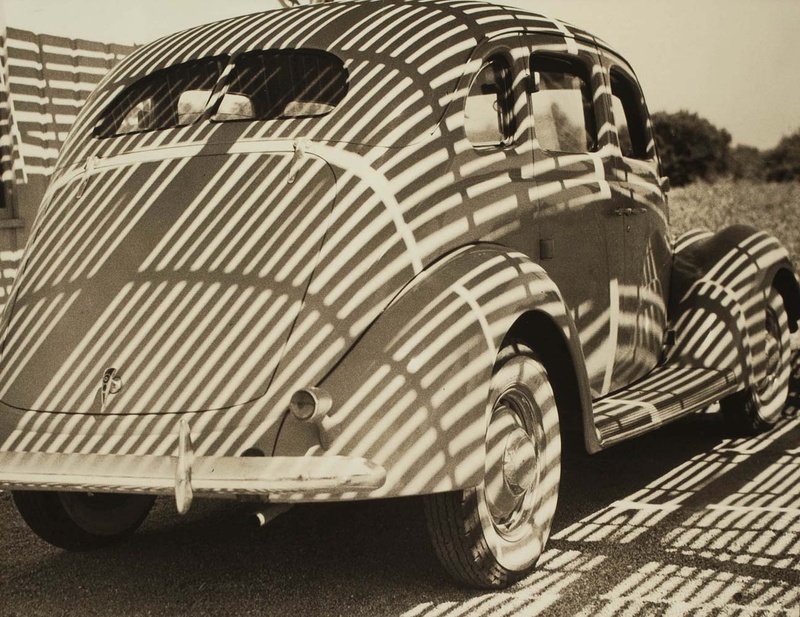

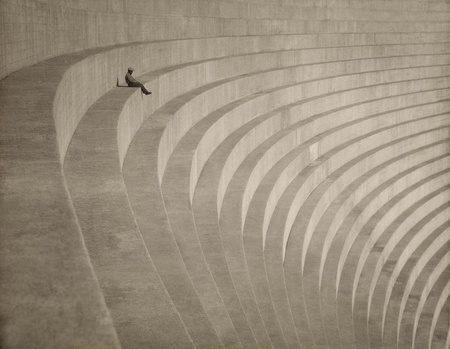

The orderly design of the universe, which was an integral part of the Japanese outlook, extended to less idyllic scenes as well, as is apparent in some Nikkei photographs. In one photograph, a tiny dark blot, barely recognizable as a person, provides a minor human accent to a cold, geometric composition, this one titled, The Thinker. The photographer, Hiromu Kira, chose as his subject the Hollywood Dam with its sweeping, curved, parallel ledges. Or consider a photograph titled Reflections on the Oil Ditch by Shigemi Uyeda. Again, simple geometric shapes prevail. A brief rain shower has left perfectly circular patches of water, appearing like lily pads, strangely floating on oil that has hardened in cold weather. This time no human figure is present to intersect the restful pattern, but the dark reflection of an off-center oil derrick in the background does. The scene is about 15 miles from Little Tokyo in Los Angeles. In an even bolder presentation, Hiromu Kira makes glass vials disappear by turning them in certain directions, leaving only luminous edges that form ghostly curves that seem to float (title: Curves).

Collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Japanese photographers adopted some unconventional European methods. The Ashiya Camera Club near Kobe, Japan, used modern camera-less processes developed by Europeans, such as photograms (e.g., light-sensitive paper alone) and montages (the overlapping of photographed images). Japanese photographers even embraced surrealism, produced by such experimental techniques as prolonged exposure, double exposure, and placing objects of varying opacity onto the negative film while the latter touches the printing paper during exposure to light. Japanese Americans were generally less willing than the Japanese themselves to deviate that much from the pictorial tradition.

* * * * *

Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940

Japanese American National Museum

February 28 – June 26, 2016

Making Waves: Japanese American Photography, 1920–1940 is an in-depth examination of the contributions of Japanese Americans to photography, particularly modernist photography, much of which was lost as a result of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. The exhibition, curated by photography historian and educator Dennis Reed, presents 103 surviving works from that period alongside artifacts and ephemera that help bring the era to life.

© 2016 Edward Richstone