Kiyoshi Izumi (1921–1996) was an impressively-educated Canadian architect who designed many iconic Saskatchewan buildings during the boom of the 1960s. His personal and professional journey, however, are just as historically important as his architectural contributions. The Japanese Canadian community in Saskatchewan of the 1940s was small, and it is clear that Izumi’s experiences as a Nisei who reached adulthood during the Second World War left an indelible impression.

British Columbia

Little is known about the early years of Kiyoshi Izumi. Born in Vancouver, British Columbia, on March 24, 1921, the son of Tojiro and Kin (both born in Japan), Kiyoshi came of age in a province where racism was, in the words of historian Jean Barman, “increasingly concentrated on the Japanese.”1 Indeed, the formative years of Kiyoshi Izumi during the 1920s and 1930s saw relative success—at least for those of Asian heritage in BC—for his cohort in school and in university in British Columbia, stoking the fears of Euro Canadians that Japanese Canadian achievement meant dealing with an Asian ethnic group on the basis of equality.

Between 1910 and 1930 the occupational base of the Japanese Canadian community had broadened from the fisheries industry to agriculture, commercial, and service occupations. This stereotype of comparative Japanese Canadian success dovetailed with the expansionist foreign policy of Japan relative to that of China and the largely non-threatening male Chinese Canadian population.2 While Euro Canadians of German and Italian heritage suffered during the Second World War, Japanese Canadians suffered considerably more. Shortly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, all Japanese Canadians were removed from coastal areas of British Columbia, most into internment camps. With this abolition of their civil rights came the loss of property and the separation of family and friends.

Saskatchewan

The residents in Saskatchewan of Japanese ancestry grew from 100 in 1942 to 153 in 1944. Among the few Japanese Canadians that resided in Saskatchewan before the 1940s were Kikuno and Genzo Kitagawa. Married in Japan in the 1920s, the young couple disembarked in British Columbia and stayed in Alberta briefly before settling in Regina in 1929. The enterprising Genzo and a business partner opened and managed Nippon Silk and while it was not lucrative during the early years of the Great Depression, the business managed to grow. The Second World War changed the dynamic for this Regina family, however. The business name of Genzo’s store Nippon Silk was changed to Silk-O-Lina, “to avoid unnecessary harassment from the public.” The Kitagawas had fears for their safety as the conflict progressed: the Silk-O-Lina’s “show-window” was broken. The family also moved from an apartment to a house “to escape the discomfort of being closely watched by our neighbours,” admitted Kikuno Kitagawa in the late 1970s. “We were sensitive to criticisms, rumours, and the reactions of people towards Japanese [Canadians] that appeared on the radio and newspapers.”3 Undoubtedly, this sense of watchfulness and tension in the Japanese Canadian community in Regina were felt by Kiyoshi and his future wife, Amy Nomura.

Kiyoshi spent his childhood and youth in Vancouver but Amy’s childhood years took place in Regina. Settling in Regina in 1933, Amy and her brother John were the children of Charles Nomura, and were among only 15 Japanese Canadian “school-aged children” in the city in the 1930s. Because of the isolation, the teenaged John Nomura and several young men in their twenties founded Shinyo Kai (roughly translated as Heart Sun Club) which existed from 1936 to 1941. Monthly dues were paid by club members in order to fund gatherings that included Christmas parties and picnics. The group disbanded after the invasion of Pearl Harbor in order to keep a low profile but some of the original members took part in the creation of the Regina Nisei Club in 1944.4

History does not record when Kiyoshi Izumi left British Columbia for the relatively less racist province of Saskatchewan. A graduate of the Vancouver Technical High School in Vancouver in 1939, Kiyoshi enrolled at Regina College in Regina, Saskatchewan in 1943. It is unclear what the young man did and where he lived between 1939 and 1943. The future architect may have had relatives in the Queen City as the city of Regina only allowed people of Japanese ancestry to reside if family members could provide assurances of financial security. To be sure, the Second World War years in Saskatchewan did not see human rights abuses inflicted upon Japanese Canadians in a similar manner as were their compatriots in British Columbia. Properties that belonged to Japanese Canadians in the province were retained by them during and after the conflict. Saskatchewan Japanese Canadians, however, were to report their whereabouts to the local Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) detachment once a month and were required to register and carry identification cards distributed by the Mounties.

In 1944, the Regina Nisei Club (RNC) was created as a support group for young Japanese Canadians in Regina and also as a collection of friends with a pan-Canadian approach under the umbrella of the “Canadian Forum” which was co-sponsored by CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company) Radio. Topics for discussion each week were selected by national and local citizens that were of a political, economic, and social nature. Occasionally, according to Arthur Kato, the concerns of the RNC were heard throughout the province and the nation.5 It is questionable how much impact the plight and concerns of Japanese Canadians in Saskatchewan had on radio listeners throughout Canada, but such gatherings undoubtedly stimulated both intellectual discussion and comradeship among the young Nisei of Regina.

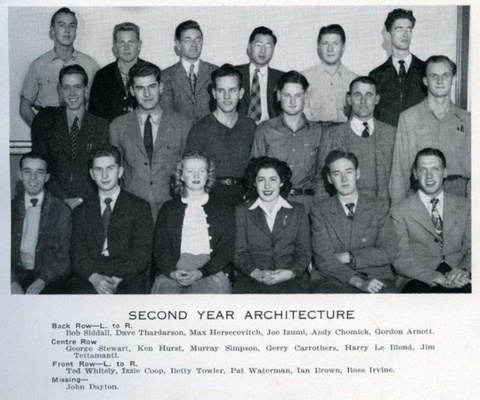

As historian Patricia Roy has shown, in 1941 Saskatchewan Premier W.J. Patterson informed Ottawa that he would accept Japanese Canadian families into his province on a “case-by-case” basis. The city of Regina accepted Japanese Canadians as residents while the city of Saskatoon did not. Saskatoon City Council bowed to pressure from local groups and individuals that expressed concern “for the safety of military and industrial establishments,” labour competition, and “resentment of an enemy race.” The city of Saskatoon refused to admit Y. Takahashi and Taira Yasumaka into the community despite the fact that the University of Saskatchewan (UofS) had accepted them. This action was representative of the reactionary response by the mayor of Saskatoon who bellowed: “The Japanese residents should be put into concentration camps… It would be foolish to move them into prairie cities. We have no room.”6 This ethnic exclusion on the part of the city of Saskatoon may explain why, after one year at Regina College (1944), Kiyoshi Izumi left Saskatchewan to attend the University of Manitoba’s School of Architecture from 1944–1948. To be sure, the UofS did not have a school of architecture but if Izumi was interested in a professional college located at Saskatchewan’s oldest university the exclusionary policy of the city of Saskatoon would have prevented his attendance.

There was a small 1940s Japanese Canadian trek from British Columbia going through Saskatchewan with the University of Manitoba as a destination. Definitely, this eastward journey was followed by Izumi and James Shunichi Sugiyama (future partner of Izumi, Arnott, and Sugiyama), British Columbians who both went to Regina College and later attended the University of Manitoba. The college experience in Regina for Izumi and Sugiyama remains a mystery. Throughout the Second World War, however, Regina College like many segments of society was a fount of patriotism and of a growing Canadian nationalism in an environment, in this instance, among service-age young people. This is reflected in an editorial by Regina College’s student newspaper the College Record in November 1940:

What is Regina College contributing to Canada’s war effort? True—we are a small group,…but why can’t we be doing more now? Other universities have compulsory military training for all male students. Our mother, the University of Saskatchewan, has compulsory “war service groups” for all women students… The big universities demand four hours a week, surely we can spend SOME time on preparedness.7

Kiyoshi Izumi and James Sugiyama were not the only members of the Regina Nisei Club that attended Regina College during the 1940s. The brothers Henry and Thomas Tamaki entered the college in 1943—the year before Izumi—as did Robert Yoneda in 1949. The Tamaki brothers attained prominence in their own right. Thomas—a winner of Regina College’s 1945 Mrs. J.W. Smith Scholarship for both scholarship and leadership—was a future lawyer who became a Saskatchewan deputy minister in the Department of Mineral Resources. Brother Henry became a vice-president of Dominion Bridge.8 The academic success of the Tamakis (and a handful of others) at Regina College and residence in the provincial capital stood in stark distinction to the city of Saskatoon’s refusal to allow them to reside in that community in 1942. In the final analysis, at least ten Japanese Canadians attended Regina College in the 1940s.

In any case, progressive change—no matter how incremental—was about to take place. Initially, Canadian Commonwealth Federation (CCF) provincial politician Tommy Douglas “remained uncharacteristically silent” on the challenges Japanese Canadians faced in 1943 and 1944 as he ran for political office in Saskatchewan. Political expediency trumped principle, therefore, in spite of his membership in a political party that claimed to champion civil liberties; certainly Douglas did not wish to be perceived as one of the few Canadian politicians to speak up publicly on behalf of Japanese Canadians even though privately Douglas found bigotry repulsive. Once safely in the Saskatchewan legislature the CCF premier began to show tentative political support for Japanese Canadians.

In December 1945 the Douglas government informed Ottawa that it would permit a “fair share” of Japanese Canadians removed from British Columbia to make their homes in Saskatchewan. This announcement was in response to the deportation of some Japanese Canadians to Japan soon after the conflict. “In our opinion,” declared the Saskatchewan premier, “the Federal government has no right to deport Japanese nationals or Canadian-born Japanese provided they have committed no act of treason.” Three months later the former Baptist preacher thundered that it was the “rankest racial discrimination imaginable” to deport Japanese Canadians reminding his audience that those of German or Italian heritage were not expelled. In 1946, Douglas reinforced his rhetoric by hiring British Columbia-born, George Tamaki, as a senior legal advisor over protests from the British Columbia political caucus of the CCF. Douglas snapped in reply: “If the existence of the CCF in B.C. depends on bowing to racial intolerance, the sooner it folds up the better.” Nevertheless, this highly public employment of Tamaki by Douglas did not include a public rebuke of his political colleagues in British Columbia. Douglas also hired Tommy Shoyama in the same year.9

Events in Moose Jaw, however, in the months after Tamaki’s hiring by Douglas proved that there could be a backlash against concentrations of Japanese Canadians in Saskatchewan. In the summer of 1946, 127 men and two women were transferred from an internment camp in Angler, Ontario, to Moose Jaw—a city of 20,000 inhabitants located less than 100 kilometers west of Regina—for the purpose of resettlement. According to the Labour Department official that enforced this relocation, “we are anxious to get as many Japanese into Saskatchewan as soon as possible so as to balance up the distribution of Japanese in Western Canada.” Initial newspaper reports would not have comforted Kiyoshi, Amy Nomura, James Sugiyama, and their cohort in Regina. Indeed, city officials in Moose Jaw were quick to condemn this decision by the federal government and tacitly supported by the provincial government. Moose Jaw mayor Fraser McClellan claimed that there was an “acute housing shortage” with “468 unfilled applications from veterans” and 370 applications “from other citizens.” Newspaper headlines in Saskatchewan screamed: “Protest Japs Located Here [in] Moose Jaw;” and “Vets Need Houses More Than Japs.” According to the Moose Jaw Times-Herald on July 20, 1946, most of the Japanese Canadian interns “were born and educated here in this dominion, and this is where they want to stay to make their homes.” At the same time, as if suffering from immediate amnesia the Times-Herald journalist also editorialized that “the Japanese are an inscrutable race and it is difficult to know just what they are thinking.” A year later, 91 people still remained in the Moose Jaw hostel because they refused to permanently settle in the province and instead, asserts Roy Miki, demanded either permission to return to British Columbia, or deportation to Japan and compensation for property losses. By 1949, the nearly 60 remaining Japanese Canadians were finally evicted from the hostel.10

Notes:

1. Barman, Jean. The West beyond the West: A History of British Columbia (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 233; Regina Leader Post, Obituary, Tuesday, October 29, 1996, Section D.

2. Ward, Peter W. White Canada Forever: Popular Attitudes and Public Policy Toward Orientals in British Columbia (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queens University Press, 1978), 111 & 117.

3. Gomer Sunahara, Ann. The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War (Toronto: J. Lorimer, 1981), 160; Nakayama, Gordon G. Issei: Stories of Japanese Canadian Pioneers (Toronto, NC Press Ltd., 1984), 131-132; 209-210.

4. Kato, Arthur. A History of Japanese Canadians in Regina. (Regina: 1980; self-published), pgs. 3; 11-12.

5. Ibid, 25-27.

6. Roy, Patricia E. The Triumph of Citizenship: The Japanese and Chinese in Canada, 1941-67. (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2007), 80; Adachi, Ken The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians (Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1976), 231.

7. University of Regina Archives, (Hereinafter referred to as URA). The College Record, November 8, 1940, 2.

8. URA. Copies of The College Record, the University of Regina calendar, from 1940-1950; Kato, 43. Thomas Tamaki attended the University of Saskatchewan College of Law after the end of the Second World War when the city of Saskatoon rescinded its residency restrictions. http://www.lawsociety.sk.ca/media/21169/bv15i5.pdf (accessed June 5, 2013).

9. McLeod, Thomas H. & Ian McLeod. Tommy Douglas: The Road to Jerusalem (Edmonton: Hurtig Publishers, 1987), 95. An assistant to Douglas, McLeod worked with Tamaki (no relation to George, above) and Tommy Shoyama in the Saskatchewan civil service. Tamaki graduated near the top of his law school class at Dalhousie University in 1941. Originally rejected by the graduate school at the University of Toronto because he was Japanese Canadian, Tamaki was accepted in 1943. Girard, Philip. Bora Laskin: Bringing Law to Life (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 144. It was Tamaki who recommended Shoyama to Douglas. http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/shoyama_thomas_kunito_1916-.html. (accessed August 21, 2013)

10. Saskatchewan Archives Board (Hereinafter referred to as SAB); “Saskatchewan Ready To Admit Some Japs.” Saskatoon Star-Phoenix, December 5, 1945; “Deportation of Japs show discrimination.” Regina Leader-Post Feb. 20, 1946.

*This article was originally published in the Nikkei Images (Spring 2015, Volume 20, No. 1), a publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre.

© 2015 Kam Teo