The other day, news broke that Prime Minister Abe will visit Hawaii on the 26th and 27th of this month to meet with President Obama and pay tribute to the victims of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Although it is not technically the first time that a sitting prime minister has visited Pearl Harbor to pay tribute, it is the first time in our memory that a prime minister has officially announced to the public that he will visit the site where the war between Japan and the United States began and pay tribute to the dead.

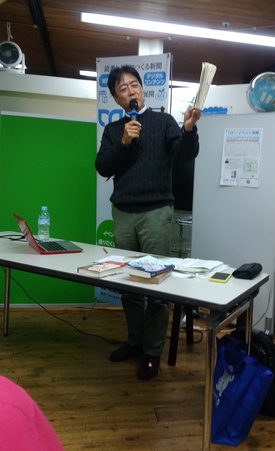

The announcement was made on December 5th, just before the 75th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor. Two days later, on the 7th, at an event space called "Mainichi Media Cafe" sponsored by the Mainichi Shimbun, I spoke about the circumstances that led to the publication of the new translation of "No-No Boy," which coincidentally begins with "the attack on Pearl Harbor," and the book's contemporary meaning.

The "Mainichi Media Cafe" holds various events planned almost every day by NPOs and companies, including "press briefings" where Mainichi Shimbun journalists talk about the contents of their interviews on current topics. The venue is a corner of the "MOTTAINAI STATION" on the first floor of the Mainichi Shimbun Tokyo headquarters (Chiyoda-ku, directly connected to Takebashi Station on the Tozai subway line), and a maximum of 30 people can gather by application (free of charge).

On December 7th, I gave a talk entitled "Talking about the phantom classic 'No-No Boy'." Around 20 people gathered, including media professionals, American culture researchers, and people on their way home from work. I titled it "the phantom classic" because No-No Boy was not well received in America when it was first published and disappeared for a time, and although a translation was published in Japan, it went out of print and Japanese readers no longer had a chance to see it.

On this day, I talked about how I, as a translator, came across this book and how it came to be re-translated and made available to Japanese readers, and the now-valuable first edition published in 1957 was circulated among the participants. I also showed photos of the author, John Okada, that had never been shown to the public before, showing what he was like when he was alive.

These photographs were sent by John's father, Yoshito Okada, a first-generation immigrant, from the United States to his family home in Japan (Asakita Ward, Hiroshima City) from before the war to after the war. I also showed him photographs of the Okada family home in Hiroshima, including the house and the surrounding area, taken when I visited there.

"No-No Boy" depicts the anguish of the protagonist, who asks "Who am I and how should I live?" This is the anguish of a man who, as a second-generation immigrant, has two countries and cultures at heart, and is forced to fight each other in a war. However, even within Japan today, there are many situations in which one feels alienated from others, to varying degrees, within organizations such as companies and schools, and in a society with inequality. In that sense, I emphasized that the anguish felt by the protagonist Ichiro is a universal theme that young people today can also face.

After the talk, several questions were asked by the participants. The first was about the differences between the old and new translations published in Japan. To this, he answered, "I think the new translation is easier to read (in Japanese)."

In response to the question, "How have your feelings about the work changed after reading it several times?" he answered, "Every time I read it, my understanding of the characters changes, and I sometimes find myself empathizing with characters that I didn't feel much sympathy for at first. I feel that the work becomes more profound with each reading."

In addition, some of the participants who looked at the first edition raised questions, such as, "It says 'Printed in Japan by Kenkyusha, Tokyo,' so it was printed in Tokyo. Why is that?" In response to this, the following was offered:

The publisher, Charles E. Tuttle & Co., is a publishing company based in both Tokyo and the eastern US state of Vermont, which played a key role in reviving the Japanese publishing industry after the war and continued to be involved in the publishing of foreign books thereafter. It is assumed that the book was printed in Tokyo because it was intended for English-speaking readers in Japan, including Americans and those on the US West Coast. As evidence that the book was intended for readers in Japan, several reviews of the book were published in Japanese English-language newspapers after its publication.

The new translation was published on the 13th, and of course the participants had not yet read it at this point, but I felt that they were interested in the author and the work.

(Some titles omitted)

© 2016 Ryusuke Kawai