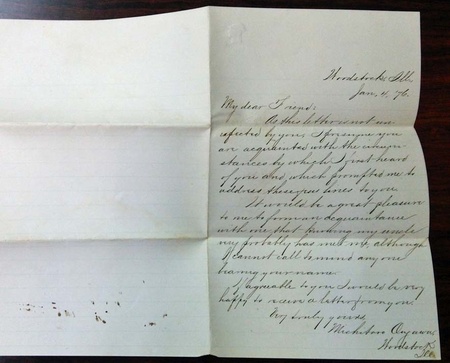

Evidence of Michitaro’s residence in the Midwest can be found in the Naniwa church, a congregational church in Osaka, Japan. Archived there are letters from Michitaro sent by him from Woodstock, Illinois, to Umanoshin Sawayama in Evanston, Illinois. Sawayama had come to the US in 1872 and was the first Japanese student at Northwestern University preparatory school.1 Sawayama had been sent to Evanston by Daniel Greene, the congregational missionary from Kobe, Japan. Why Evanston? Because Greene’s brother Samuel and sister Anna both lived in Evanston. They took care of Sawayama for four years until he returned to Japan in 1876.

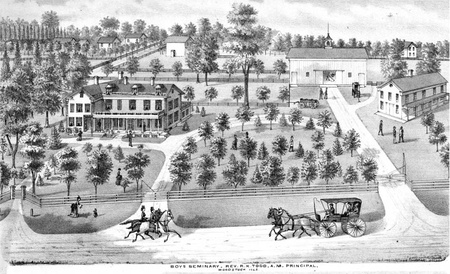

When Michitaro was writing letters to Sawayama in early 1876, he was a student at the Todd School for Boys in Woodstock. The Todd School was founded by Reverend Richard Kimball Todd, a graduate of Princeton Seminary in New Jersey—the same school that Reverend Dodge had graduated from. It is logical to speculate that Reverend Dodge sent Michitaro to his friend’s school when he left for San Francisco.

In a letter to Sawayama, Michitaro expressed his joy at making contact with a person who probably knew his uncle, saying: “I infer from your letter that you were acquainted with my uncle…if you knew my uncle you very likely knew me.”2 At Reverend Greene’s home in Kobe, Michitaro’s uncle-in-law, Masanosuke Otsubo—Yoshiyasu Ogawa’s wife’s brother—had also studied English with Sawayama. How denominational differences affected Michitaro’s relationships with his two uncles, one of whom is Presbyterian while the other is Congregational, is unclear at this point. However, Michitaro’s words are testimony to the tightness of the missionary network in 19th-century Japan—a network that made an immense contribution, despite denominational differences, in the modernization of Japan and its people.

The May 31, 1877, issue of the Woodstock Sentinel quoted a section of Michitaro’s speech at a Ladies Foreign Missionary Board event in Chicago: “It is to their kind and generous assistance that I would acknowledge a debt of deep and lasting gratitude. To them and to the work of foreign missions I am indebted for all that I now enjoy in this Christian land, for I was once a heathen in the far off isles of the sea.”

Michitaro seemed popular at the Todd school; he was nicknamed “Mitchie” and the school had a lawn party “for his benefit.”3 He lived in Woodstock for about five years. After graduating from the Todd School, he enrolled at a Presbyterian school, Lake Forest University, in 1878.4 He also enrolled as a freshman in the collegiate department of the University of Chicago in 1879.5 There is no evidence that he finished both schools with diplomas.

According to the 1880 census, Michitaro was 21 years old, single, living on Water Street in Chicago, and working as a clerk at a dock company. As the Woodstock Sentinel reported on July 1, 1880, “Mitchie,” a student at Lake Forest University, spent a few days of the week with Mr. Todd’s family; he may have then been a working student. He also used the English name Michael.6 He moved to Austin, a suburb of Chicago, around 1882, but kept working in Chicago.7 Although he often changed jobs, the types of jobs he held were consistent: clerk, bookkeeper, accountant, and cashier.

Michitaro was naturalized in October 1884 in Chicago.8 He married a white woman, Clara Page, in Austin in September 1891.9 Clara was well known in the musical circles of Chicago and Oak Park as one of the leaders of the Beethoven club, and in Austin as a leader of church choirs.10

The 1900 census shows that Michitaro and Clara lived with Clara’s parents and sister in Chicago. Around 1909, they moved to Oak Park, where Clara had held a teaching job at Bliss Music School since the fall of 1907.11

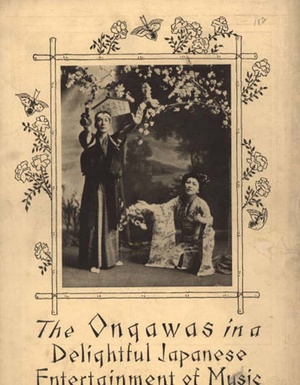

It is not yet known how and when the Ongawas got involved with the Chautauqua traveling performance circuit, choosing a life in the world of theater, where they presented traditional Japanese culture in the form of songs, musical instruments, dance, and stories. They spoke English in their performances, and it was said that “they spoke such fluent English that until one listened carefully one fancied they were Americans artfully made up as Orientals.”12

Reports of their performances appeared in the popular media between 1908 and the 1930s. One of the earliest articles was about Clara’s performance at the Woman’s Club of Austin, titled A Glimpse of Japan. Michitaro loaned her a collection of Japanese prints for the event.13

After the big success of their first musical, Along the Road to Tokyo, it seems that some time after 1914, Ongawa signed a contract with the Radcliff Attractions Chautauqua circuit and started performing with Clara in the eastern US, from North Carolina to New Hampshire.

They lived in Oak Park for about six years, between 1909 and 1915. The 1920 census shows that they moved back in Chicago to live with Clara’s sister. In the census, Michitaro and Clara listed themselves as travelers for educational work, indicating that they had finally found their life’s purpose. In the 1920s, they performed at Columbia University in New York, the University of North Carolina, and Illinois State University at Normal.

Michitaro Ongawa died at the age of 79, on July 30, 1938, in Chicago. He was buried in lot number 113 S1/2, section 43, in Forest Home Cemetery in Forest Park. His grave does not have a stone marker. This may be because many cemeteries in Chicago had a policy of refusing to bury Japanese Americans during and after the war. In one report made after the war, Forest Home Cemetery announced that they “fought this out in court many years ago and won a decision to prohibit any but Caucasians to be buried therein.”14 The marker for Michitaro Ongawa may have been removed during a period of such anti-Japanese sentiment.

Michitaro Ongawa was one of the earliest Japanese Americans in Chicago. He played a unique role in promoting multiculturalism in early 20th-century America. His long 19th-century journey from Yokohama, Japan, to Chicago and the Midwest embodies the American dream of fulfillment and success that the Presbyterian missionaries who sent him to the US did not expect at all, but probably could strongly embrace.

Notas:

1. Catalogue of Northwestern University 1872–1873, page 28.

2. Michitaro Ongawa’s letter to Sawayama, dated April 30, 1876, Naniwa Church, Osaka, Japan.

3. Woodstock Sentinel, June 14 and 21, 1877.

4. General Register of Lake Forest College 1857–1914, page 37.

5. 21st Annual Catalogue of the University of Chicago 1879–1880, The Old University of Chicago Records 1856–1890, Box 5B, Folder 18.

6. The Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of Chicago, 1881.

7. Chicago City Directory, 1885.

8. Certificate of Naturalization, dated October 31, 1884.

9. Marriage License No. 172500, dated September 14, 1891.

10. Oak Leaves, October 15, 1910.

11. Oak Leaves, September 21, 1907.

12. “Mr. and Mrs. Michitaro Ongawa.” Official Registry and Directory of Women’s Clubs in America, 1922 (X–XI).

13. Chicago Daily Tribune, March 22, 1908.

14. List of Cemeteries Contacted for Lots for Orientals. Chicago Oriental Council. Collection of the Japanese American Service Committee, Chicago.

* This article was based on a paper presented at the 18th annual conference on Illinois History on October 7, 2016, in Springfield, IL.

© 2016 Takako Day