Japanese people involved in Kabuki

In November, I received an email from the Japan Foundation announcing an event, as usual. It was about a film adaptation of the stage play starring Ichikawa Ennosuke that had been a big hit in Japan, "Super Kabuki II One Piece," to be screened at the Chinese Theater in Hollywood. There, I saw the name of Akira Oshima Mark as a commentator. Upon investigation, I found out that he was a Japanese-American born in Colorado. He is a Kabuki researcher, a translator, and even a Kabuki performer as a Kiyomoto-bushi narrator. I was intrigued as to how he had entered the world of Kabuki. I requested an interview, and he kindly agreed to meet me at the hotel in Los Angeles where I was staying the day before the event.

Oshima's parents were born in Tokyo. They met in Minneapolis while they were both studying abroad in the 1950s. "They came to America at a time when the exchange rate was 360 yen to the dollar and there was a limit on the amount you could take out of your pocket. It was a time when it was difficult to come to America from Japan without a special reason. My father, who graduated from the University of Tokyo, didn't really want to study abroad in America, but he was encouraged by his grandmother (his mother) and studied plant diseases first at Colorado State University and then at the University of Minnesota. My mother's family used to run a trading company in Ginza that dealt in European paintings and ukiyo-e, but they lost everything in the Great Kanto Earthquake and the family was suddenly in poverty. So my mother worked and saved money to come to America. She studied at a university in the southern part of the United States, then majored in home economics at the University of Minnesota and obtained a master's degree," Oshima said, smoothly talking about the circumstances that led to her parents' move to America.

Eventually, his father got a job teaching at Colorado State University, and they moved to Fort Collins, Colorado, where Mark was born in 1960. His younger brother, Ken, is five years younger than him and currently teaches at the University of Washington.

Studying in Japan in 1981 was a turning point

What was Oshima's family environment like when she was a child? Was Japanese spoken on a daily basis? Was Japanese culture familiar to her?

"In fact, English was the language spoken mostly in the home. Both my mother and father had learned English before they met. Even so, my father would jokingly say 'Hurray!' when he was taking off my shirt. And then, when we were going to the movies, he would say things like 'Let's go see a moving picture,' even though that phrase has long since become obsolete in Japan (laughs)."

When Oshima was nine years old, her mother opened the store. At first it was called East West Art Centre and sold crafts, but eventually Japanese gifts and food products became the main product, and the store's name was changed to East West Imports. The store also began offering Japanese culture classes. "My mother had a unique way of teaching Japanese, and when it came to writing she mainly taught katakana. In other words, the idea was that if you mastered katakana, you would be able to write kanji. My mother was also very sociable and active, hosting tea parties for the wives of Japanese university professors."

During New Year's, a party was held for university staff and international students. Everyone brought something to cook. The Oshima family mainly cooked red rice and ozōni. In addition to university staff, the Japanese community in Fort Collins also included Japanese people who had been sent from other states to internment camps in Colorado during the war and who remained there after the war. "But I think there was a gap between us, the new generation of Japanese people, and them," Oshima recalls.

A turning point came for the Oshima family, whose father taught at a university and whose mother ran a shop, when Oshima was 16 years old. His father suddenly passed away from a subarachnoid hemorrhage. "It couldn't have come at a worse time. My mother had designed and was building a new house, but the house wasn't finished and we didn't have insurance. What's more, my father was 47 when he died, so he was still young and didn't have enough social security or pension. It was only after we moved to the new house that we were finally able to hold a funeral for my father."

However, with the help of his mother, the family overcame the difficult times and Oshima entered Harvard University. After completing his third year, his mother almost forced him to study abroad in Japan.

"My mother said that if you know both Japanese and American culture, you will be able to choose," he says. His mother, who had studied in the US of her own volition at a young age, was convinced that by sending her son to study in Japan, he would broaden his future options. Oshima took a leave of absence from Harvard from 1981 to 1982 to study at the International Christian University (ICU) in Tokyo. "At ICU, I began going to see Noh, Bunraku and Kabuki performances with a friend from university. At that time, my friend heard about an English earphone guide at the Kabukiza Theatre, so I made a sample and applied, and to my surprise, I was accepted."

Traditional performing art, Kabuki, up close

After completing his one-year study abroad, Oshima returned to Harvard. Before studying abroad, he had thought about becoming a lawyer in the future. He had also decided to write his graduation thesis on "Colonial Policy in Manchuria." However, after returning to Japan, the topic changed to "Social History of Kabuki." The course of his life changed dramatically during his one year abroad.

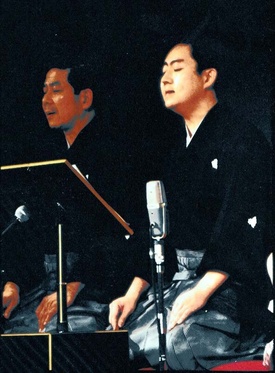

During his graduate school days, he volunteered as an interpreter for a New York performance, which led to his interactions with Bando Tamasaburo and the second generation Onoe Kuroemon, who taught drama at Harvard and Columbia University. In 1987, he enrolled at Waseda University as a Japan Foundation fellow. During that time, he encountered Kiyomoto-bushi and later became a Natori. His first professional performance was in "Sumidagawa" performed by Tamasaburo. And this year marks the 30th anniversary of Oshima's planned one-year stay in Japan.

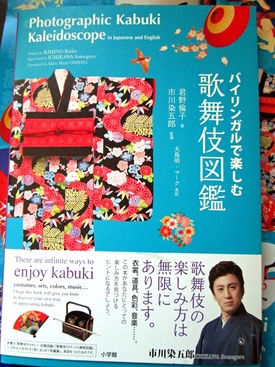

Oshima is currently based in Tokyo and works as a Kabuki researcher and Kiyomotobushi narrator, but three years ago she began working as a translator for the NHK program "Kabuki Kool."

"Interest in Kabuki among young Japanese people today is waning. Even Kabuki One Piece is a work that could be considered unorthodox. But I think it's a good thing if it can spark an interest in Kabuki. My job is to introduce Kabuki, a traditional form of Japanese culture, so that Japanese people can feel closer to it, and also so that foreigners can become familiar with it. When I came to Japan as a Japan Foundation fellow in 1987, the condition was that I would stay in Japan for a year and then return to the United States to spread the Japanese culture I had learned. But I ended up staying in Japan. By explaining Kabuki to Americans like I did this time, I feel I have finally paid that price."

© 2016 Keiko Fukuda