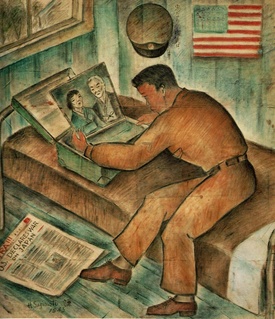

He produced an incredible amount of work in the camps. There were two different paintings that I wanted to ask you about. The first is called Final Decision. It looks like a Japanese American soldier looking at a picture of his parents with an American flag on the wall. Can you describe what that’s about?

Well the fact is that during, being in camp, many of the young fellows wanted to join the army which is ironic when you think they’re in the camp. And so I think in that, my father tried to capture the sense of a young man wanting to join the army or having joined the army and still he was in camp but he joined the United States army to become a serviceman. So I think there’s an irony in that. But it was not something that was unusual because that did happen. There were young men who wanted to become U.S. soldiers in the army.

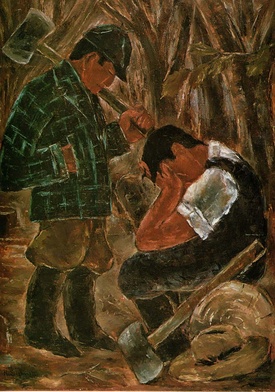

I think that debate is still alive in terms of where people discuss the loyalty of the camps, and it’s so powerful. I think the other painting that speaks to that similar theme is called Am I An American Citizen? And it’s two men who are out chopping wood and one man has his head in his hands and the other man is consoling him. How does that also speak to that conflict of belonging?

I believe there was confusion and ambivalence about being in a camp behind barbed wire yet at the same time, still wanting to serve in the army because you were an American citizen. I think that’s the kind of sense that was also in the air in the camp and my father tried to capture it, by putting it on canvas that way with images of people confused and not knowing exactly, ironically being in a camp and yet wanting to serve the very government that put them in the camp.

In that way your father became a journalist to chronicle all the conflict people were feeling. Were people interested in the fact that he was producing work in the camp and did people want him to paint certain representations of anything?

I never heard my father and mother speaking about it. My sense is that my father was trying to capture images of the experiences in camp but it was not to be “for” or “against” the government. It was his sense of being an artist and trying to capture in images, the emotional environment in which people were living. But nobody ever asked him or said you should do it this way or that way. My father, I think, felt very comfortable to do what he felt he wanted to express, not because somebody or people asked him to do it. It was his own feelings that he was expressing. I don’t think he felt swayed one way or another. As an artist he was expressing what he felt in terms of his own experience or what he saw and then putting it on canvas, rather than having any political notion about what was being put on canvas as such.

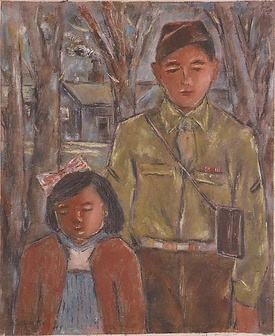

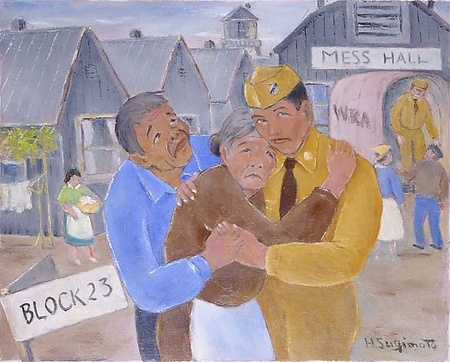

Which is what is so powerful about having these pieces of work. The paintings give a very clear depiction of what was going on. And you had an uncle who was in the U.S. army, correct?

Yes, Uncle Ralph. That’s my father’s third, there were four brothers in his family, and he was one of four. And so Uncle Ralph is one of his younger brothers and he was in the service.

And was he the only one out of the brothers that served in the military?

Yes, that’s correct. Because the others weren’t of the age where they would be put into service. My father being the oldest, and Uncle Ralph being younger so I think by age, in between, would not be eligible just because of their age.

Can you sum up some of what he went through in the army?

Well, he was in that segregated 442 Infantry Battalion and he talked about being in Sicily and Italy. I believe in that sense it was trying to keep the Japanese American service members away from Japan and the Asian area because of the conflict it would have between being a Japanese American and being a service member and then being in the place where they’re fighting against their own people, in a sense, of Japan. And my uncle, I think he was the one who talked about having shrapnel that injured him. So that he talked about it long after the war and the fact that he was in the fighting in Sicily and Italy.

I didn’t put that together, that they would keep the 442nd logically away from the fighting in Asia.

Well I don’t know that there was any army decision, I’m just thinking behind the reason why they didn’t go to the area of Japan area or Japan and China area. I don’t really know, because there wasn’t anything that I read or said that was the reason why they did it so that’s my own thinking.

When you relocated to New York, did you move with other Japanese Americans that were going as a group or were you one of the very few families that did?

Well it was because my father having had a really wonderful experience in New York as a younger man that brought us to New York. It was really a family decision rather than any kind of a community decision. But certainly there were others who came, later on we learned who were in camps. But it wasn’t a decision. He wanted to come to New York.

Do you have a story or image in your mind that you think of when you think of your time in the camps?

Well for me, it was really a happy time as a child because we lived very much as children, going to school and having playmates and doing things that we probably would’ve done outside of the camp. And so for me, the camp experience was not a sad or typical one. It’s only that I know having learned later on coming to New York where different Japanese Americans got together and would talk about things and also my family saying how difficult it was—the uncertainty of the future that I learned about it. But as a child it was always something that was a happy time.

I only know through what I read that you worked in healthcare but what did you do professionally?

Yes well, I became a nurse. And then after I worked at Cornell New York Hospital and graduated from Cornell New York Hospital School of Nursing and worked there. And as I continued to do my work, I enjoyed the contact I had as a staff nurse with some of the students who would come to the unit from outside the hospital for their clinical experience and I enjoyed it very much. And I enjoyed it very much but I believed that if I was going to work with students in that capacity then I would need more of an education. So I enrolled in teacher’s college and got my two Master’s in education and curriculum and I continued to teach at the School of Nursing.

And that’s what you did your whole career?

Yes I really stayed. I identify myself more as being a nurse educator although I was a staff nurse in the very beginning but my career was really a nurse educator.

In this current political moment that we’re in, what do you feel we need to really be aware of in order to not repeat mistakes?

I think the experience of us, the Japanese Americans, comes alive more now when you think about the Muslim population. And the fact that after 9/11, the Muslims being looked upon as very suspicious and people that we couldn’t trust. And I know that the feeling that when they said “round them up,” was an expression that was used to round us up to put us into internment camps in the very similar idea that has been talked about of rounding up Muslims and profiling them and looking at them suspiciously brings back memories of people that were perfectly innocent and good citizens and people living in the community contributing that I feel is happening to the Muslims because of what’s happened in the Middle East. I think there’s much more of a sympathy for them in terms of what they experience because we were also separated and put into a specific category of people that couldn’t be trusted at one time, so it’s really to support the Muslims as a responsible people who live and work as equally responsible and should be looked upon as citizens and people to be accepted and welcomed and part of the regular community.

With what’s going on politically and in the world that this would be a reminder of something that happened to a group of people who were being condemned for something they didn’t do anything.

*This article was originally published in Tessaku on November 5, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida