“I think that as a child, I feel that I was protected because my parents and their friends and my grandparents never really spoke about anything in regard to what was happening. So later on as I grew older, and I talked with them, then I found out how fearful they were.”

-- Madeleine Sugimoto

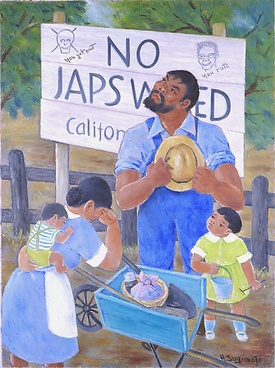

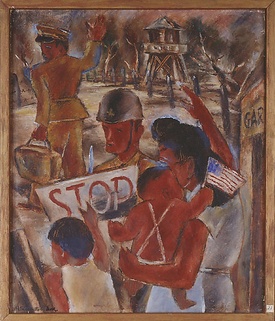

As the only daughter of renowned artist and painter Henry Sugimoto, Madeleine Sugimoto has the immense responsibility of caring for the legacy of hundreds of pieces he created. “Whatever work my father had here in the city [New York], I donated all of the artwork to the Japanese American National Museum. It was not only oil on canvas, but he did watercolors and he did block printing.” Madeleine donated three large canvas murals to the Smithsonian Museum of American History and her father’s work is on display at Hendrix College in Arkansas, the state where the Sugimoto family was held in Rohwer during the war.

What do you remember when Pearl Harbor happened?

I remember that after Pearl Harbor my father was in a young men’s group in Hanford that was a mix of Caucasians and Japanese Americans. And one of his friends said to him, “I think you have to be careful.” Because my father had taught Japanese language on the weekend to people in the community and young students. And this friend knew that and said, “You know, because you taught Japanese language, the FBI may be after you.” With that, my father prepared a small suitcase in which he put in some of his daily needs and was prepared because he thought that perhaps the FBI would come after him.

It was reinforced because one of my grandfather’s friends came over to say that his friends had been taken away by the FBI. Of course, we all were under curfew so that every night by 9 p.m. we all had to be in our homes. So those were some of the things I remember shortly after the bombing.

Did the FBI ever come for your father?

No, fortunately not. But it was always a feeling that something might happen that was with the family. I was certainly not aware as a child that was happening. I only learned of it after.

And did you have any siblings?

No, I was an only child. But as an only child I would say, I think there was no worry or fear on my part. I think that’s probably true of children in general. If you’re with your parents, you don’t really fear or have an anxiety as long as you’re not separated from them and so I think that’s why there was nothing in me that I could remember as being worrisome as a child.

I’ve gotten that sense from other people I’ve spoken to who were children in camp. That it seemed to be a happier time because it was like a big gathering. I read in one of your interviews that there was a moment you thought everyone was at a picnic. Could you retell that?

What happened was we were sitting at those wooden picnic tables with the benches. And we were having a meal and there were the other people from our community sitting around the other tables. And when we finished the meal I said, “Oh, when are we going to be going home?” And that’s when my parents said we’re not going home, this is where we have to stay. And so that’s the time when I realized it wasn’t really a picnic, as I always thought. So that’s the time when my mother or father said we weren’t going to be going home, that where we were is where we’re going to stay.

I think it’s interesting that’s the way you remember it. The perspective is so different as an adult. Do you remember your parents being worried or feeling like they were uncertain about what was going to happen?

I think that as a child, I feel that I was protected because my parents and their friends and my grandparents never really spoke about anything in regard to what was happening. So later on as I grew older, and I talked with them, then I found out how fearful they were and worried because they didn’t know what was going to happen next. And it’s only after I got older that I realized the anxiety and terrible experience they had with being evacuated into an internment camp.

Were your parents open about talking about the camps or were they quiet about it?

No, they were very, very open about it. After we left the camp and went to New York City, we came directly from Arkansas to New York City. My father, as an artist, was continuing to paint. And he was continuing to put images on canvas of experiences in camp and because of that, and hearing what he said talking to my mother or to friends, that I realized what had happened. So there are images my father has painted of camp life that help me to remember.

But I can remember specifically as a child, that I had three playmates and we decided we would go exploring. And that’s when we went outside of the barbed wire fences and into the swampland in Arkansas. So as a child, I would say that it was a happy time because I was doing what I probably would do if I were not in camp—had playmates and did the kinds of things we did which was going exploring. And remembering the fact that there was a boy scout troop and a girl scout troop and I was only six so I joined the Brownie scouts. So there were different things that I remember as a child, that was probably very similar to it would be like if I was outside of camp.

Your life wasn’t as interrupted because of your age. But do you feel that your father was interrupted, career-wise?

Well I believe that he was able to do sketching and different kinds of painting in camp. And how he did that was when we first went into the camps, all our property that we carried with us in the camp was wrapped in those raw canvas. So my father, once we went into the barracks went around the area and said to the neighbors, “If you’re going to throw away that raw canvas would you please give it to me?” So he even used the raw canvas for as a source for his painting. And the fact that my mother and he had both graduated college and my mother taught first grade and my father taught high school art. They were certified by the state of Arkansas so that they could be considered teachers in the school system in the camp. And my father continued to do what he was able to do which was be an art teacher and be able to do the painting and sketching that he wanted to do during the free time. So I believe it was close to how he actually would be living as an artist if he was outside the camp.

Was your mother an artist too?

No, my mother didn’t want to do any art. She enjoyed working with children and that’s why she became a first grade teacher in the camps. She didn’t have any talent nor even try to do anything with art. She just met my father in Hanford when she was in high school and my father and she and his parents lived nearby so that’s how they got to know each other.

So your parents were Nisei?

My mother was born in Hanford but my father was born in Wakayama and then he came to the United States after both his parents came to the United States and were living in Venice, California. So he was not an American citizen until it was permitted later on.

Do you speak Japanese?

I did when I was younger but I no longer speak it. One of the things is that my father being from Japan felt more comfortable speaking Japanese so my mother and he spoke Japanese and with that I understood a little bit but really never spoke Japanese except a little as a child. Once we left and went into camp we all communicated in English except for my mother and father who continued to speak Japanese to each other.

And you were in Jerome, correct?

Yes, it was first Jerome and when Jerome closed, we were in Rohwer. From there we came to New York City.

Was New York where you wanted to go regardless?

Yes, that was his choice. When the government said we could leave the camps, and go wherever we wanted to, my mother and father must’ve talked about it and because my father was an artist and had come to New York earlier, he had experienced the enjoyment and the activities of being an artist and so my mother agreed.

*This article was originally published in Tessaku on November 5, 2016.

© 2016 Emiko Tsuchida