Clotilde Yamasaki never knew her father's real name. He only remembered that his countrymen, Japanese immigrants like him, called him “Torak.” In Peru he was baptized as José.

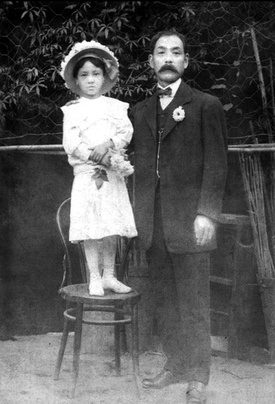

One of the few things she knew about her father, a silent and reserved man, was that he had arrived in Peru accompanied by an uncle on the Sakura Maru , the ship that brought the first Japanese immigrants to the country on April 3, 1899. .

The mystery would be solved by Jorge Ávila Cedrón, Clotilde's grandson, in 2013, 25 years after his grandmother's death. Without his tenacity, probably no one in his family would have ever known the name of “Torak,” his hometown, or the circumstances of his trip to Peru.

Jorge went to the General Archive of the Nation and the National Library, but the search for information about his great-grandfather was fruitless. He then decided to go to the Museum of Japanese Immigration to Peru, where they lent him the book The First Immigrants of Japan , by Juan Iida.

In the list of immigrants who arrived in Peru on the Sakura Maru , Jorge found two Yamasaki, a nephew and an uncle. The nephew's name was Torakichi and he had been assigned to the La Estrella sugar mill, in Santa Clara, Ate, where Clotilde was born and raised. Everything fit. Jorge had found what he calls the “missing link.”

The book contained other information about his great-grandfather, such as his year of birth (1870) and the prefecture he came from (Niigata). The discovery was a shock. “I remembered everything that had happened to me looking for the name, I was crying,” he says. He thought of his grandmother Clotilde. He took out a copy of the page that collected the information about Torakichi and spread it among his entire family. His enigmatic great-grandfather finally had an identity, an origin, a story.

His interest in his Japanese ancestors on his paternal side (his father was Clotilde's son) was born a long time ago. In the 1980s he interviewed his grandmother to ask her about “Torak”, her relationship with him and her childhood.

Clotilde told him that her father was a carpenter and married her mother, Juana Sami, in Santa Clara, who died after giving birth. He was 20 years old. Her father raised her alone and never remarried. His mother is a mystery. No photo of her survives and Clotilde apparently did not know any of her mother's relatives. Jorge Ávila does not rule out that Juana was of Chinese origin (in Santa Clara, Chinese immigrants formed a large community) and even that she was Japanese (she would have been baptized Juana in Peru).

Torakichi left two daughters in Niigata. Like every immigrant at that time, he planned to fulfill his work contract and return to Japan. Meanwhile, he sent money to his wife and daughters in Niigata.

However, Torakichi lost contact with them and never saw them again. He stayed in Peru forever. He never returned to Japan.

After finding out where his great-grandfather came from, Jorge Ávila investigated it thoroughly. Perhaps no one knows more than him in Peru about the town of Kameda and the neighborhood of Funatoyama where Torakichi lived. Learn about its history, what it was like when your great-grandfather migrated, what the main activities of its inhabitants were and what it is like today.

The only thing missing is to see Niigata in situ, where he probably has family, descendants of Torakichi's two daughters. With the discovery of his great-grandfather's identity he closed one chapter of his family history, but another awaits him in Japan.

A LOVING MOTHER

Clotilde Yamasaki was born in 1908. She was one of the first Nisei in Peru and perhaps also one of the first Peruvian-Japanese mestizas. She never met her father's uncle because he returned to Japan before she was born.

In the interview that Jorge Ávila did with her, Clotilde recalled her childhood at the La Estrella sugar mill, where the Japanese worked in the sugar cane factory.

“I was very restless. They called me 'huacha' (for being an orphan of a mother). I would get on the cane carts, pull the canes and throw them. I told my dad's countrymen, 'Cut this cane for me!' I went where they ground the cane, from above I watched how they worked. From there I ran to the factory, where my father was. They told me 'be careful the machine hurts you'. He worked alone in the carpentry. In front were the mechanics. Everyone used to annoy me 'ñata, ñata'. Even the boss himself told me, 'hey ñata, come'. I didn't pay attention, I just went through another door."

The girl Clotilde wanted to climb into a jar to get honey. He couldn't, but he still managed to get away with it.

“Since it was a Japanese who was there, I wanted to get on it to get honey. 'No, no, no, it doesn't go up, it doesn't go up, I'll get the honey' (the Japanese said), and he took out the honey. 'Now run, run, before the owner comes,' and I was going to go home to my house."

When Clotilde married Patrocinio Ávila, her father Torakichi, upset because his daughter was marrying without his consent, distanced himself from her. Clotilde left Santa Clara to move to Vitarte, where her husband worked in a textile factory.

When Clotilde and Patrocinio had their first child, a girl, Torakichi kept his distance. However, when the second child was born, a boy, he resumed contact with Clotilde to meet his grandson.

Torakichi worked at the sugar cane factory until its closure in 1932. He died in 1936 and lived his last months at his daughter's house under her care. She remembered her father as a person who was not very communicative and was sparing in signs of affection.

In the papers Clotilde appeared as Yamasaqui, the same as her father. In her baptismal certificate (1908), Torakichi appears as “Yamasaqui, a native of Japan”; on the marriage certificate (1935), as “José Yamasaqui”.

Pedro and Juan, two of Clotilde and Patrocinio's sons, were in charge of rectifying the surname to Yamasaki.

Clotilde tried to teach her children a little Japanese, but since these were children, they did not pay much attention. Furthermore, she had no contact with the Japanese colony, so she had no opportunities to practice the nihongo that she had learned as a child with her father.

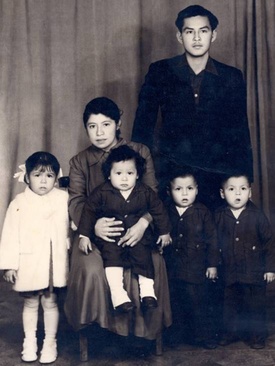

She was a loving mother who pampered her ten children, to the point of preparing different dishes, two or three, to try to please everyone. Since she did not have the opportunity to study, she always showed special interest in her children's education.

Clotilde suffered a hard blow in 1964, when her husband died in the tragedy at the National Stadium that claimed the lives of more than 300 people due to the referee's decision to annul a goal against the Peruvian team in a match against Argentina for a quota. to the Tokyo Olympics, unleashing popular anger. To contain the crowd, the police threw tear gas bombs into the stands and hundreds of fans, trying to flee, found the doors closed and were crushed. Patrocinio went to the stadium accompanied by some of his children and a niece who survived.

HISTORY FOR THE FUTURE

Jorge Ávila jumped from family history to general history. Several, actually. To that of Niigata, but also to that of Santa Clara in the times of his great-grandfather and his grandmother, and that of the Japanese immigration to Peru.

It was not enough for Jorge to discover his great-grandfather's name, the date of his birth or where he was born. He also wanted to find out why Torakichi decided to migrate, what the Japan he left was like, what kind of country the Peru that received him was, how the first Japanese immigrants lived, what the situation was at the La Estrella sugar mill, etc. To try to get to know Torakichi I needed a context.

Thus, he discovered that of the first 790 Japanese immigrants, 116 were assigned to La Estrella. Between 1899 and 1913, 419 people from Niigata migrated to Peru. However, Japanese prefectural authorities decided not to send more people to Peru due to complaints about poor labor. Many even returned to Niigata.

The Japanese suffered mistreatment from the landowners. Jorge clarifies, however, that it was not directed particularly against them, but also against other exploited groups, such as the Chinese or blacks. “It was a problem of idiosyncrasy of the upper classes,” he explains.

During his research process, a singular event occurred: he found the email address of a Niigata government official and decided to write to him in search of information about migrants to Peru. He did it in three languages – Spanish, Japanese and English – using Google Translate. Just in case. Three languages better than one to understand each other.

Although the official responded at first that he was not dedicated to those issues, he later had the gesture of writing to him again to apologize and send him information about the migrants from Niigata to Peru in 1899. He also found out if there were relatives of Torakichi (descendants on his part). of his daughters) in his town, but he found no one.

Jorge Ávila, who recently graduated as a professor specializing in history, continues researching. Every door you open is an encouragement to find the next one.

In the search for her roots, the sentimental component has been very powerful as a motivating force to persist for a quarter of a century, from the time she interviewed her grandmother until she discovered her great-grandfather's man.

Jorge highlights the importance of history, of “recognizing our past not to stay there, but for the future, to learn lessons, to understand where we are in order to plan for the future.”

Ávila, who worked for 25 years in NGO development projects, aspires to leave the fruits of his research as a legacy to his descendants so that they know their origins and have a basis from which to reflect with an eye toward the future. . The story continues. “We continue to build history,” he says.

When he thinks about the reasons that pushed Torakichi to migrate, he states that “the human race is a migrant, it always looks for new scenarios to solve its personal problems.”

124 people in Peru descend through a direct line from Torakichi. And to think that some of his countrymen, loving uncles, suggested taking Clotilde to Japan when she was a child. Clotilde preferred to stay in Peru with her father. 124 people, from children to great-great-grandchildren, thank you for your decision.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 104, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2016 Texto y fotos: Asociación Peruano Japonesa