From the Meiji Era Opening Up to Overseas Emigration

As the years go by, the ugly grass loses its roots and is transplanted.

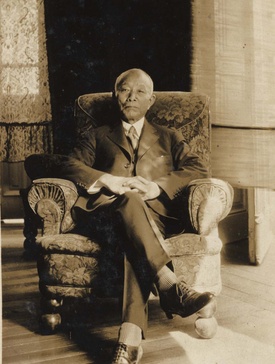

In the home of Fumio Oura in Suzano Fukuhaku Village, a framed version of this tanka poem, handwritten by Mizuno in his final years, is displayed. Oura named an overpass in Suzano City after Mizuno Ryu in honor of his achievements. As a token of appreciation, Mizuno Ryu's widow, Maki-san, left the poem there.

The comparison of Japan, with its ancient traditions, to an "ugly grass" is 120% filled with the love and hate feelings toward the good and bad aspects of one's sad hometown. The song expresses the desire to cut off the roots, replant it in new soil, and let it bloom as a beautiful Yamato Dianthus.

When I visited Ryuzaburo's home, I learned that he lives a simple life, making and selling yakisoba noodles at a food stall to make a living.

The son of Ryu Mizuno complained, "In months when sales are not good, we can't pay the electricity bill and it gets cut off." This fact alone suggests that Mizuno ended his life without leaving any assets to his descendants. Mizuno was not a man who made a killing in the immigration business.

In a lecture titled "Why Ryoma Now?" given in São Paulo on October 20, 2010, Professor Haraguchi Izumi of Kagoshima University (at the time) said, "If Ryoma had lived, he might have spent his life emigrating and pioneering. His desire to venture overseas may have resonated with Mizuno Ryu."

"If Ryoma was alive at the time of the Kasato Maru, he would have been 73 years old," says Professor Haraguchi. Even if he was too old to have traveled to Brazil, it cannot be denied that he may have been involved in the migration project in some way.

On page 162 of his book "Letters in which you can hear the voice of Ryoma" (Mikasa Shobo, 2011), Professor Haraguchi Izumi paraphrases a portion of a letter written in March of the year Ryoma was assassinated, which reads, "This time, we have already rented a ship to go north," as "As for the Hokkaido development project that we had been planning to start last year, this time we have already rented a ship."

Ryoma believed that the development of Ezo would determine the future of Japan, and explains that "while he was at the Kobe Naval Training School, he was already making plans to move ronin to Ezo to work on its development and defense."

If he had not been assassinated, he would have arranged to charter a ship to depart between mid-March and April 1 of the following year. If that had gone well, it would have been only a matter of time before Ryoma himself would have traveled to Hokkaido.

Eight days before he was assassinated, Ryoma wrote to Mutsu Munemitsu with excitement, "I don't know if the talk of going out into the world will work out, but I've heard about it. There's been a mountain of interesting stories lately" (ibid., p. 176).

The development of Ezo and the argument for opening up the country must have led to overseas migration. Ryu Mizuno, a Tosa samurai, was one of these lions of the Meiji era.

The Sakamoto family goes to Hokkaido, while Mizuno goes to Brazil.

Along with Kitazoe Kimihisa and Mochizuki Kameyata, a student at the Kobe Naval Training School, Ryoma had dreamed of developing Ezo (Hokkaido) since around 1864, and it seems to have remained a cherished wish until his death.

Professor Haraguchi emphasizes that Ryoma's approach of creating a new world (a settlement) in Ezo and finding a new frontier, rather than taking the "path of war" where many people would die, was a peaceful solution. "If he had migrated, there would have been no discrimination against indigenous peoples such as the Ainu, and the world might have become a more peaceful place," he says.

However, on November 15, 1867, Ryoma was assassinated at Omiya in Kyoto, and the Meiji government was established the following year. Hawaiian immigrants, known as "Gannenmono," crossed the ocean. Professor Haraguchi says, "At the time, going to Ezo, Hawaii, or Guam was the same feeling."

The Sakamoto family itself moved to Hokkaido in 1897 (Meiji 30) when the fifth head of the family, Naohiro, moved the entire family, so there are no members of the family left in Kochi.

Kochi Shimbun journalist Kazukata Tomio wrote the following in his book Southward (100 Years of Kochi Prefecture Migration to Central and South America) (Kochi Shimbun, 2009):

"Sakamoto Naohiro, a fellow civil rights activist who traveled to Hokkaido, was six years older than Mizuno Ryu. Sakamoto's Hokkosha pioneer group left Urado Bay and settled in the northern lands via the Japan Sea route before Mizuno traveled to Brazil. There is no mention of Sakamoto in Mizuno's biography, but there is no way that Mizuno would not have been aware of Sakamoto's challenge."

In fact, when I asked Ryuzaburo, he replied, "My father often told me stories about Ryoma Sakamoto." Although there is no evidence that they exchanged letters directly, they were both born in the Tosa domain in the same era, and there is no doubt that at least Ryu Mizuno was strongly influenced by Ryoma Sakamoto.

By the way, Sakamoto Naohiro was the fifth head of the Sakamoto clan, a local samurai clan in the Tosa domain, and Sakamoto Ryoma was his uncle. He was also a activist for civil rights and a Christian pastor. The passion for developing Ezo that Ryoma aimed for was passed on to Sakamoto Naohiro, who took over from his nephew Sakamoto Nao (Takamatsu Taro), and took root in Hokkaido.

Surely, the "opening of the country" and "development of Ezo" must have been followed by "overseas migration." The beautiful Yamato Dianthus that was transplanted to Brazil is now blooming beautifully in various fields of society.

Mizuno Ryu has received too much praise and criticism to be called a great man. However, the Meiji Restoration patriots were by no means all saints. Rather, it was because Mizuno Ryu was an "unconventional man" that he was able to start the immigration to Brazil, something that no one else had done at the time.

© 2016 Masayuki Fukaawa