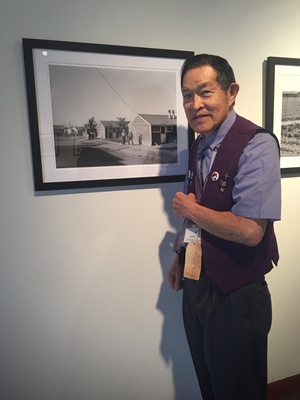

Museum volunteer and docent James Tanaka thought something was missing from an exhibition and it bothered him.

The Japanese American National Museum’s long-running exhibition, Common Ground: The Heart of Community, seen by more than one million visitors, chronicles the history of Americans of Japanese ancestry from the 1800s to the present. In one of its text panels, the exhibition mentioned that some Japanese Americans who had been unjustly incarcerated in concentration camps during World War II were temporarily released. The reason for the release was that laborers were urgently needed in other parts of the country to help with agricultural work. Tanaka knew that there was an important story behind that subject because he had lived through it.

“Japanese Americans helped the war effort,” Tanaka says. “But they haven’t been getting the credit that was due to them.”

During the war, sugar was a critical commodity. Beyond its use in food, sugar beets were essential for making industrial alcohol and used in the manufacturing of munitions and synthetic rubber. Serious labor shortages in the agricultural industry made harvests difficult—and Japanese Americans like Tanaka answered the call for help.

Tanaka and his parents were among the thousands of Japanese Americans who left the camps to work in sugar beet fields. Though he was only a child at the time, Tanaka joined in the hard manual labor. His story, along with many others, is part of a new exhibition, Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II. The exhibition was organized by the Oregon Cultural Heritage Commission and features the work of noted Farm Security Administration (FSA) photographer Russell Lee, who documented the Japanese Americans’ efforts in Oregon and Idaho.

“I got involved with the project when I read an article in the Pacific Citizen about [exhibition curator] Morgen Young attempting to identify photos taken by Russell Lee,” Tanaka says. “I didn’t know any of the men, but Morgen wanted people who had lived in the farm labor camps. I e-mailed her and she came down to the Museum and interviewed me to be part of Uprooted. I am the only one from South-Central Idaho. The others are from Eastern Oregon.”

“We stayed in shelters for a $1.50 a week, similar to the WRA center barracks except ours had wood siding and shingles on the roof,” Tanaka recalls. “The restrooms, washbasins, and toilets were in rows between the barracks, with the showers and wash tubs next to the mess hall at one end of the barracks. The room also had a large wooden cover over the screened window opening that was pushed out to provide air. The room was furnished with beds and a table and two chairs with a pot-bellied stove to heat the room. Next to the highway was the FSA labor office and the medical and dental offices.”

“Sugar beet work started in the spring as the beet seedling appeared above the ground,” Tanaka says. “This continuous row of seedling requires blocking with a short handled hoe to provide growing space. Thinning eliminated the weeds and tiny beet seedling, so the worker would pull the weeds and leave the strongest beet seedling.”

The summer work, Tanaka explains consisted of removing weeds with a triangular blade attached to a small handle or using a long-handled hoe. The fall harvest was the busiest time, and with a shortage of workers, children were released from school to help with the harvest.

“Harvesting of the sugar beets required a large knife with a hook on the end,” Tanaka says. “The beets would be lifted and the hook would be used to raise the white three- or four-pound beet to the other hand. The knife would be used to remove the beet crown and leaves. The beets would be thrown into a row wide enough for a truck to drive along while the workers did the hard work, throwing the beets into the truck bed.”

“A light beet might be thrown over the truck and could hit that side worker,” Tanaka remembers. “A worker could earn more money than working in the center. Three girls earned $8.40 for a day’s work, being paid a $1.40 a ton.”

Tanaka notes that the work was physically demanding and dirty. “The workday might be eight to ten hours. My mother wore a bonnet to provide shade from the sun. You brought your own water and lunch to the field. Restrooms did not exist in the field then. For men it was easier than for women. Face away from the people; find a tree, shrub, or a ditch to use as the toilet. This created a problem for my mother as she had a bacterial infection of her knee which caused it to be permanently locked.”

The laborers also harvested other crops. “Strawberry harvesting required the workers to be in the field before the sun rose. Picking would begin with the first light. Enough berries were harvested by noon to provide the day’s supply at the store, so you had half a day’s work. The hardest work was harvesting the hay or alfalfa. The work began after cutting and baling took place by machine. Men would use hooks to lift the bales onto the truck bed, while another worker would stack the bales. These bales were sold or stored for the winter feed of cattle and were restacked. Potatoes had to be cut up into quarters to provide spring seedling from the eyes of the potato.”

Tanaka was just eight years old during this period. “Child labor laws were in effect, especially during the school year,” he says. “I attended a one-room schoolhouse at the FSA camp. Each bench was one grade, and we were all taught by one teacher.”

His time in school left an imprint. Eventually Tanaka attended college, receiving a bachelor’s degree and teaching credential from California State University, Los Angeles. He became a teacher of science and health/safety and taught for 39 years. He estimates that approximately 10,000 students passed through his classrooms during his long career.

After retiring in 2000, Tanaka became a volunteer at the Japanese American National Museum and found a new way to be an educator—as a docent, leading tours of the Museum’s historical exhibitions.

Reflecting back on his time in Idaho, Tanaka says that despite the anti-Japanese hysteria of the era, his non-Japanese classmates treated him with respect. Years later, he contacted a classmate to send him the local newspaper’s address so that he could place an ad to thank his classmates for treating him like a fellow American, which he was. “I am certain this helped me survive those years. I don’t know how I would have turned out if I was treated as an invisible person.”

Through his patient work as a volunteer, Tanaka strives to make other Japanese Americans visible too. He’s pleased that WWII-era farm laborers are finally getting recognition that they deserve, more than 70 years later.

* * * * *

Uprooted: Japanese American Farm Labor Camps During World War II is on view at the Japanese American National Museum from September 27, 2016 to January 8, 2017.

© 2016 Japanese American National Museum / Darryl Mori