Kenji Yamazaki, who gave up his position as a member of parliament and sacrificed himself for love and the romance of pioneering in South America

A representative example of postwar left-wing immigrants is Yamazaki Kenji (1902-1958, Gotemba City, Shizuoka Prefecture).

He was elected to the Numazu City Council in 1931, became a permanent executive committee member of the Social Mass Party the following year, and was elected to the Shizuoka Prefectural Assembly in 1935, building up a fast-paced career.

In the April 1962 House of Representatives election, he won the top spot (Shizuoka 2nd District) and climbed the ladder to becoming a politician at the age of 35. In 1964, he married Michiko Fujiwara (from Okayama Prefecture), a comrade in the socialist movement who was two years older than him.

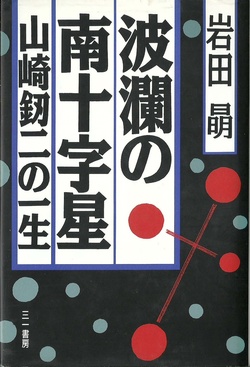

Nikkei Shimbun "60th Anniversary of Postwar Immigration" = Former Representative Yamazaki Kenji, who sacrificed his life for the development of Seinan = Sequel to "The Southern Cross Doesn't Lie"

According to "The Southern Cross in Turmoil" (Iwata Sayaka, Sanichi Shobo, 1994), the proletarian writer Tokunaga Sunao stayed at the young Yamazaki couple's home for two weeks to conduct research and attracted so much attention that he wrote a novel about the peasant movement called "Red Love."

However, he was buffeted by the waves of the times as the Imperial Rule Assistance System was firmly established, and in 1940 the Social Mass Party, to which Yamazaki belonged, was dissolved, and the labor movement was also banned. Feeling that he had reached his limits in political activity, Yamazaki tried to find a way forward in the south, so in April 1942 he left his wife and children behind and boarded a fishing boat from Yaizu at Kobe Pier, attempting to stow away to Borneo.

The Chief of Staff of the Borneo Garrison was impressed by Yamazaki's reckless actions and appointed him as the governor of Keningau as the army governor. Although it was a violent region that had seen rebellions in the past, he surprised the local people who were waiting for him when he arrived there alone with an interpreter.

He was well-known locally as a "great governor" and served as the site supervisor himself, cutting down the jungle and building the "Yamazaki Road", a 20km-long main road that also served as an airport. Yamazaki fell in love with Ain, the younger sister of a local employee, and made her his secretary and local wife. In 1942, Yamazaki was 40 years old and Ain was only 17 years old.

When he returned to Japan in 1946 after Japan's defeat in the war, Yamazaki felt a strong sense of responsibility as a man and took back with him Ein and their two children who had been born overseas. This incident was dubbed the "two-wife" incident in Japan and caused an uproar in the media.

Yamazaki and her husband returned to Japan just before the first general election (1946) in which women were allowed to vote and run for office. At that time, Yamazaki's wife, Michiko, ran for office at the request of the Socialist Party and was elected in first place in the prefecture. In the second House of Representatives election, the couple ran in the same constituency (Shizuoka 2nd District), but Michiko won and Yamazaki lost, completely reversing their positions.

Meanwhile, Yamazaki ran for mayor of Numazu in 1949 as a reformist candidate, but lost to the Liberal Democratic Party candidate. He returned to the Numazu City Council in 1951, but was defeated in the 1952 House of Representatives election, coming in eighth.

The following year, a film of the same name, "The Southern Cross Is True" (Shintoho), was made based on Ain's memoirs, with Takamine Mieko playing the heroine Yamazaki Ain, which became a hot topic. Yamazaki was struck by misfortune when his eldest son with Ain drowned on the Numazu coast, and his second son contracted Japanese encephalitis. Yamazaki gave up on his career as a politician and decided to try a second life by "moving to the Amazon" in 1954.

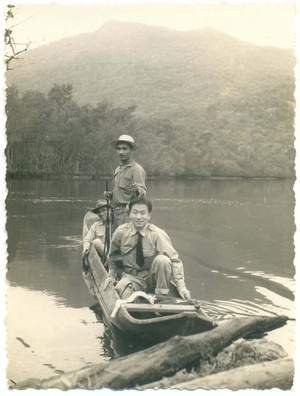

As Ain missed the climate of the Southern Ocean, Yamazaki thought, "I will realize in South America the dream of pioneering that I was unable to achieve in Borneo." He went to the Amazon with the help of his fellow countryman, Yamada Yoshio (from Numazu City, Shizuoka Prefecture), who was engaged in extensive business in the Amazon River basin. However, they were unable to come to an agreement, and Yamazaki soon went to São Paulo.

After that, Yamazaki worked on a Brazilian farm in Peruive, on the southern coast of the state of São Paulo, as a contractor for the development of the farmland. He rented an apartment in the Oriental district of São Paulo, where he had his wife and children live, and moved to the farm alone.

According to Sakao Hidenori (a Brazilian music critic), who stayed in Yamazaki's apartment for about a year, Yamazaki was often asked, "What is the point of coming to such a remote place and cultivating something, when you were a member of parliament in Japan?" He recalls that Yamazaki would always reply, "Believe in one thing and work hard to cultivate it, isn't that enough?"

Sakao remembered the deceased, saying, "He was a man who had the qualities to become a governor who was well-liked by Borneo people, a man with a strong sense of justice and passion."

Four years after arriving in Brazil, just as his work was finally getting on track, Yamazaki died of liver cancer at Santa Cruz Hospital (formerly the Japanese Hospital) in São Paulo on January 31, 1983, and an unusual funeral was held for people from the prefecture.

Despite his advanced age, he continued to work on developing remote areas, and perhaps the strain took its toll -- he passed away at the age of 55. The Shizuoka Prefectural Association, led by Matsumoto Keiichi and others, held a lavish funeral for Yamazaki.

A left-wing immigrant who lived a romantic life

There is a reason why there are few intellectuals among the "immigrant" "race." To adapt to a completely different culture, a certain "carelessness" is necessary, but intellectuals tend to think logically that "things should be like this." As a result, they tend to want to exactly recreate the environment in which they formed their personality in their new home, and after going through a lot of hardship, they tend to "give up halfway."

Economically speaking, those whose families have a strong financial situation are more likely to receive a good education from an early age and, as a result, to be highly educated. In other words, those from wealthy families are more likely to become intellectuals, and from the start, they are distinguished from the flocks of people who migrate in search of a better life.

In terms of personality development, people with less education tend to be "less logical." They tend to be more "careless" about how things should be, and have acquired an attitude of "not striving for high ideals." Therefore, even if their ideals and reality differ, at some point they tend to be relatively obedient and compromise, thinking, "When in Rome, do as the Romans do, so there's nothing I can do," and tend to accept it.

The core of the Japanese immigrant community in Brazil were poor, poorly educated families from rural areas, headed by the second or third son of a farming family. While trying to revive the "Japanese-style village society" in South America, they adapted to the local situation, retaining some Japanese thinking and culture, and this movement can be said to be the history of the Japanese communities known as "colonias."

There were very few international students or highly educated people there, so even if innovative political ideas were brought over from Japan, there was no basis for their spread. Of course, the statements of compatriots in Brazil hardly received any attention in Japan. In this environment, there was a small but growing trend of left-wing intellectuals, as mentioned above.

The left-wing immigrants were all excellent at reasoning, but terrible at business. They lived romantic lives in difficult circumstances, and were somehow human.

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa