Although they are simply referred to as "Japanese immigrants in Brazil," each person has their own unique motivation for moving to the other side of the world.

Of course, generally speaking, most of them came from a place of "seeking a better life," but in reality, they were motivated by poverty, new opportunities, and starting over, and many of them had conservative ideologies. However, there was also a small group of "left-wing intellectuals seeking political asylum." This time, I would like to introduce some of these people.

* * * * *

In order to avoid repeating the same fate as Southeast Asia, which had been colonized by the West, the Meiji government was pushing for centralization and nationalism in order to become a "strong nation." Many "freedom and civil rights activists" who sought a nation centered on the people, in opposition to the Meiji government's efforts, fled to the West Coast of the United States to escape oppression.

The newspaper medium itself has always had a strong stance of criticism of the government, and even in Japan, freedom and civil rights activists were often involved in the founding of newspapers, but a similar tendency could be seen in Japanese-language newspapers overseas.

One of these was the Japanese language paper "Shin Nihon" (New Japan), which was first published in Oakland, a suburb of San Francisco, in 1887. Although it had a small circulation of just 200 copies, it was an opinion paper for political refugees. It was mailed from the US to Japanese newspapers and leftist activists, and had a huge influence throughout Japan through these channels. As a result, the Meiji government went to the trouble of banning the paper in 1888, forbidding its sale and distribution.

The North American community before World War I was made up of many Japanese students and political refugees, and the intellectual level was generally high. Many of them had worked for Japanese newspapers for a time. Many of the reporters who gained experience of North America in this way later became active in the Japanese media.

For example, there is Kawakami Kiyoshi, who contributed articles on diplomatic relations from New York and Washington to the Mainichi Shimbun; Yoneda Minoru, who wrote diplomatic and international commentary as chief of the Asahi Shimbun's foreign news department from the Taisho era through to the Showa era; and Kiyosawa Rei, who was active as a diplomatic and political commentator before the war and wrote the Dark Diary, a valuable record that sheds light on military control during the war, which was published after the war.

Katayama Sen, who is said to be a major contributor to the Russian Revolution, is said to have made a living from working for a Japanese-language newspaper in San Francisco during his exile in the United States, and then traveled straight to Leningrad to join the revolution.

Japanese immigrants to the United States were different from immigrants to Brazil in several ways. First, the United States was the center of Japanese diplomacy after the Meiji Restoration, and there were always many students studying in the United States. Their knowledge and experiences were easily recognized in Japan, and it was easy for them to return home.

However, because Brazil is geographically too far away, it has always been one of Japan's "neighboring countries," and as a result, the Brazilian community has created its own unique immigration history, like a kind of "cultural and ideological Galapagos Island" isolated from Japan.

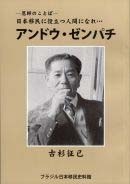

Zenpachi Ando, known as the "Communist Immigrant"

When I spoke with Wakisaka Katsunori, advisor to the São Paulo Institute of Humanities, the only institution for researching immigration history in Brazil's Japanese community, in December 2011, he told me an interesting anecdote.

"Ando Zenpachi said that when he returned to Japan temporarily in 1928, he "unwillingly tore up his Brazilian Communist Party membership card and threw it into the sea" off the coast of Yokohama Port. He knew very well what would happen if he brought something like that back to Japan at that time. There weren't many people who were called Communist immigrants at the time, but there is no doubt that he was one of them."

Ando Zenpachi (real name Kiyoshi, 1900-1983, Hiroshima City, Hiroshima Prefecture) was an intellectual and first-year student of Portuguese at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages.

To commemorate the 110th anniversary of Ando's birth, Furusugi Masami (director of the National Institute of Humanities), who spent a year researching Ando's life and organized a special exhibition, writes, "The son of an army officer, he received a strict education from a young age. Influenced by his teacher at middle school, Eto Eikichi, he became an avid reader of Nakae Chomin and other works, and began to embrace enlightened ideas and became interested in Marxism" (Brazil Special Report, Newsletter of the Japan-Brazil Central Association, May 2012).

Ando joined the Kanada Maru as an immigration supervisor in July 1924, and also served as a reporter for the Brazil Times and editor-in-chief of the Japan-Brazil Newspaper, making him a man with deep ties to Japanese-language newspapers.

The anecdote that he took the name "Zenpachi" (Zenpachi) because "I'm a man who has no connection with money, so I'll break down the kanji for 'money' and make a sarcastic remark," is symbolic of his way of life.

After the war, he organized a private study group called "Saturday Club" (the predecessor of the São Paulo Institute of Humanities), but he was ultimately unable to adapt to life in Brazil. He was a romantic who was married three times and returned to Japan after the war, leaving his wife and children behind in Brazil, and eventually returned to his hometown and remarried the woman he had first fallen in love with.

Just when one thought he had completely severed ties with Brazil, he published "The History of Brazil" (1983) through Iwanami Shoten as the final book of his life. Even though he returned to Japan, he must have had some strong feelings about it.

Keiichi Matsumoto loses his place in Japan after defending workers' rights

An even more die-hard fan was Matsumoto Keiichi (1886-1976, Yaizu City, Shizuoka Prefecture) before the war.

After graduating from Shizuoka Junior High School (now Shizuoka High School), he went on to Sendai Second High School and was baptized by Danjo Ebina. This marked the beginning of his lifelong commitment to Christianity, and from then on he firmly embraced and practiced the belief that "I will take on what others are unwilling to do."

After graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture at the Imperial University (now the University of Tokyo), he entered an agricultural research institute in Kurashiki City, Okayama Prefecture, run by Ohara Magosaburo (a Christian who served as president of Kurashiki Spinning Co., Ltd. and built the Ohara zaibatsu).

Following strong urging from his former teacher, he attended the Third International Labour Conference (the annual general meeting of the International Labour Organization, ILO, founded in 1919) held in Geneva in April 1921 as a "workers' representative," a move that dramatically changed the course of his life.

When the "workers' representative" at the first conference was selected by the government, labor organizations at the time started a protest movement, and it was a role that none of his friends and acquaintances from his time at the Imperial University, who had risen to professorship and bureaucrat status, wanted to take. Therefore, Matsumoto accepted the role with the conviction that "if I don't do it, someone else will be sacrificed."

Following the orders of his university mentor, "Do what you have to do and say what you have to say," Matsumoto maintained his position, which was in direct opposition to representatives of the Japanese government and Japanese employers, and was praised by representatives from other countries. Matsumoto's advocacy of "tenant farmers' rights as workers" was an international standard that was not understood in Japan at the time.

In the end, Matsumoto's opinion was adopted at the conference, and as a result he was treated as a traitor by the Japanese authorities, became a major issue in the House of Representatives, which was dominated by representatives of feudal landlords, and faced extremely strong criticism, making headlines in the newspapers.

At that time, Japan was in the midst of the great wave of Taisho democracy. The number of labor unions had increased dramatically from 107 in 1918 to 432 by 1923, and it was a time when workers' rights began to be loudly advocated. The conference began in 1919, and the standards decided there, such as the "8-hour work day," became concrete goals for labor union movements in various countries.

After the conference ended, Matsumoto spent a year studying abroad in 12 European and American countries, including Germany, and deepened his knowledge of labor and social issues before returning to Japan at the end of 1922.

However, when Matsumoto returned to Japan, he found no place for himself. In 1924, with the help of Ohara, he traveled around South America, where he was given 4 alqueres of land in Itaquera, São Paulo, and decided to emigrate. Although his classmates strongly encouraged him to join the peasant movement and social movements, Matsumoto declined, citing his intention to go to South America, and instead moved to Brazil with his family of four in 1926.

An old friend from elementary school wrote, "If you had stayed in Japan and been active in the peasant movement, you would have been a brilliant activist for the Socialist Party by now, and I regret to say that you will be missed." (History of the Emeboy Training Center, by Masuda Shuichi, published by the same publishing committee, 1981, p. 33) If he had stayed in Japan, he might have become a close friend of Yamazaki Kenji, who will be mentioned later.

In 1931, he was appointed director of the "Emeboy Training Center." The training center was built under the initiative of the Overseas Industrial Company, with the aim of "fostering mid-level leaders for the colony." Kaiko's president, Masaji Inoue, was a man of ultranationalistic leadership ideals, such as "stretching the Imperial Way," and had a colonial theory based on the idea of "All the World in One Place," and wanted to educate the trainees in line with that.

However, Matsumoto paid no attention to such things and stuck to his "spirit of self-reliance and self-effort, liberal educational policy." As a result, the "shrine problem" arose.

Kaiko Honsha entrusted the first batch of students with the sacred object of Amaterasu Omikami (a charm from Meiji Shrine) and instructed them to build a shrine to enshrine it within the training facility, but Director Matsumoto was adamantly opposed. "Here too we can see the conflict between national prestige and development and the idea of a paradise for permanent residence," writes Ando Zenpachi in "Forty Years of Immigrants" (1949, edited and written by Kayama Rokuro, p. 310).

When the Emeboy Training Center was founded, Brazil was in a period of instability, having just taken power after the revolution of Getúrio Vargas in 1930. Matsumoto already had the foresight to foresee the possibility that Japanese and Brazilian nationalism would come into conflict later, creating the possibility that Japanese immigrants would be persecuted.

Although the training center only operated for about seven years from 1931, it produced many talented people who went on to support the colonia's literary, art, journalism and other fields in the postwar period.

Among the 171 graduates were a succession of figures who inherited their mentor's liberal ethos and played key roles in the postwar Japanese community, including Masuda Shuichi (pen name: Tsuneka), an early Paulista newspaper reporter who later worked hard to popularize Portuguese haiku; his brother Masuda Kenjiro, also a Paulista newspaper reporter; Homma Takeo, who returned to Japan just before the outbreak of war and published Nostalgia (Hobunkan, 1951), a full-length novel about Japan's first win-lose struggle; Maruyama Masahiko, a leader in the postwar Colonia music world who served in such positions as director of the Brazilian Musicians' Association and president of the Japan-Brazil Musical Association; botanist Hashimoto Goro; and Saito Hiroshi, who became editor-in-chief of the Paulista newspaper and later a professor at USP.

Interestingly, the Masuda brothers, Saito Hiroshi and others became key members of the study group "Saturday Club" that Ando Zenpachi established after the war. They must have had similar personalities.

The training center was forced to close down in 1938 as a result of the "Order to Crack Down on Foreign Language Schools," which was one of a series of hardline nationalist policies implemented by Vargas after he established his dictatorship in 1937. The nationalistic conflict between Japan and Brazil that Matsumoto had predicted became a reality.

After the lab closed, he devoted himself to agricultural research at his family farm in Itaquera. As Matsumoto was an academic who had no regard for money, Mrs. Masu suffered unspeakable hardships. "When the lab closed and their income was cut off, it would not be an exaggeration to say that the household was in a state of 'absolute poverty', and they were unable to provide for their sons' education, and they even walked barefoot to school. Even in those times, Matsumoto, a scholar, never lost his enthusiasm for agricultural research. For this reason, it was difficult for his family to 'grade' him as a husband and a father..." (Emeboy Lab History, p. 43).

Matsumoto worked with his fellow townspeople to found the Shizuoka Prefectural Association in 1930 and became its first chairman. He served in that role for 25 years until 1955, when he passed away in 1976 at the age of 90.

© 2016 Masayuki Fukasawa