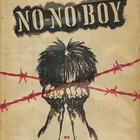

The novel "No-No Boy" reaches a major climax in the second half of the story. Ichiro's mother and his close friend Kenji pass away one after the other. These two deaths appear at the same time in the eighth chapter. How did the author, John Okada, portray these two deaths?

Kenji lost a leg in the war, and the injury worsened, so he was hospitalized in a veterans hospital in Portland. Ichiro visited his friend and looked for a job there, but eventually decided to return to Seattle. As Kenji had asked, Ichiro drove Kenji's Oldsmobile to his parents' house.

There, Ichiro meets his kind father, who asks him about Kenji's condition at the hospital, etc. At first, Ichiro answers in order to avoid worrying his father, but his father seems to know the truth and honestly tells him that Kenji is on the verge of death.

Then, Ichiro's father tells him that Kenji had already passed away without Ichiro's knowledge. Ichiro is shocked, and his father tells him the words that Kenji had spoken before he died, as if it were a will.

In Chapter 7, Kenji is on his sickbed and talks about his ideal of wanting the afterlife to be a world of only humans without racial distinctions, but here he talks about another ideal. This time, he talks about his aversion to Japanese people (Japanese-Americans) being united together. Looking at it from another perspective, this is also a reaction against being obsessed with race and ethnicity.

Ichiro's father tells him the words he had previously exchanged with Kenji.

"'When I die, don't worry about me, Dad,' he said. 'No fuss, no big funeral. If it happens when I'm in Portland, let those guys over there dig a hole.' He said, 'If you put me in the Washali graveyard with the other Japs, I'll come back to you, Dad. I've got an idea for where I'm going next. I want to start right in the next world.'"

The "Washari Cemetery" mentioned here is actually a large cemetery in the suburbs of Seattle, where many Japanese and Japanese-American graves are lined up. The grave of John Okada, who was born in Seattle, is also located in Washari Cemetery.

Although it would have been natural for him to join the washari, Kenji chose to have his ashes thrown into the sea. His father, an Issei, speaks to Ichiro with regret and sorrow about the sensitive and problem-conscious Kenji.

"She was a good girl, fun, thoughtful, and everyone liked her, but she wasn't really happy. The other kids didn't seem to worry so much, they just told themselves that things would work out the way they would, and they were doing pretty well. That wasn't the case with her. She was always wondering why things were the way they were. I often think that for her sake, I should never have come to America. I should have stayed in Japan. In Japan, she could have been a Japanese girl, surrounded by only Japanese people. And maybe she wouldn't have had to die. But it's too late now to think that."

Sad end of my mother

At Ichiro's house, his mother's behavior began to become strange shortly after his younger brother Taro went to serve in the US military, despite the family's objections. She would repeatedly do pointless things and would not eat. His worried father didn't know what to do and turned to alcohol to ease his stress.

How did it come to this? In the midst of his complaints and reflections, his thoughts went all the way back to before he married his wife. It was when he took his wife at a betrothal party or something in Japan. The father spoke to himself, as if calling out to his wife (Kinchan).

"...Yes, Kinchan, it was a mistake. We should have waited, and everything would have been fine. We made a mistake, and now we suffer. Your father, my father and mother, and that man did not know, but God did. We stood there in the dark, and God looked, and nodded, and said. How shameful, how shameful."

After this, his father gets drunk and passes out from exhaustion and despair. Ichiro returns from Kenji's house and finds something strange happening in the house. He then discovers his mother, who has committed suicide, in the bathroom. Seeing his mother sinking in the bathtub, Ichiro is overcome with pity and sympathy for his mother.

"It was a mistake to leave Japan. It was a mistake to leave Japan and come to America and have two sons. And it was a mistake for Mom to think that she could keep us completely Japanese in a country like America. As for me, Mom did a good job raising me, or maybe it seemed that way. Sometimes I wish she had done it perfectly well. She would have been happy, and I might have found a sense of completeness as a person. But the mistakes she made were so many and so big that it became impossible for me to avoid them. I felt sorry for myself for a long time. And suddenly I feel sorry for my mother. I feel sorry for her not because she died, but because she never knew happiness. (Omitted)... Now, you're free. Come back immediately. Come back to Japan, the place you've always loved and never forgot. And be happy. That's what's best. I can't believe I'm only beginning to feel this way after my mother died, but maybe that's just how it is. I found out too late that my mother was unhappy. It was only after she died that I was able to understand her a little, and I even grew to like her a little. It couldn't have been any other way. Even if she had lived another ten years, or even twenty years, it would have been too late.

Stories of parent-child relationships where the parents are unable to understand each other while they are alive are heard everywhere, both in the East and the West. It is not difficult to imagine that in the case of relationships between first and second generation immigrants in a country with a different language and culture, things can become even more complicated.

Ichiro's relationship with his mother was similarly complicated and unhappy when she was alive, but that too faded with her death.

(Translation by the author)

© 2016 Ryusuke Kawai