It took two attempts to bring the first gift of cherry trees to the United States from Japan. The first shipment of 2,000 trees in 1910 were not healthy enough to plant. The second shipment of 3,000 trees from Mayor Yukio Ozaki of Tokyo to the city of Washington, D.C. in 1912 were a success! It is the recognition of that gift that sparked the National Cherry Blossom Festival along the Tidal Basin.

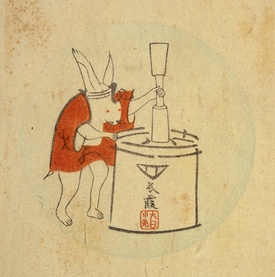

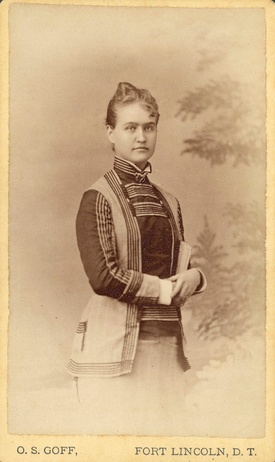

It was an idea with roots in the late 19th century, with the writer Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore. Scidmore was an aberration. She wrote the first travel book for Alaska and was the first woman to write for National Geographic. Scidmore wrote about her experiences traveling in Asia and lived in Japan. She would write about Asia for decades, introducing American readers to the Japanese moon festival and that while Americans saw a “man in the moon,” in Japan the image on the moon’s face was seen as “rabbits making mochi.”

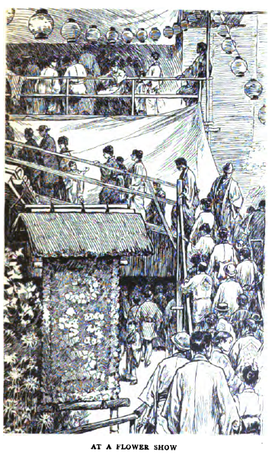

While she wrote about cultural traditions and flower festivals—such as the festival in Japan for the asagao, or morning glory—Scidmore also was acknowledged as an insightful observer of the social and political environment in Asia, publishing works like Java: The Garden of the East in 1897, and China: The Long Lived Empire in 1900.

The U.S. National Park Service (NPS) credits Scidmore as the first to advocate for cherry trees in 1885.

“Upon returning to Washington from her first visit to Japan,” reports the NPS, Scidmore “approached the U.S. Army Superintendent of the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds, with the proposal that cherry trees be planted one day along the reclaimed Potomac waterfront. Her request fell on deaf ears. Over the next twenty-four years, Mrs. Scidmore approached every new superintendent, but her idea met with no success.”

In 1909, Scidmore made the request of the wife of President William Howard Taft, first lady Hellen Herron Taft, suggesting she would fundraise to buy the cherry trees and donate them to the Capitol. The NPS explains that the First Lady had lived in Japan and was familiar with the sight of the cherry trees in bloom.

Hellen Herron Taft responded to Scidmore in two days, writing:

“Thank you very much for your suggestion about the cherry trees. I have taken the matter up and am promised the trees, but I thought perhaps it would be best to make an avenue of them, extending down to the turn in the road, as the other part is still too rough to do any planting. Of course, they would not reflect in the water, but the effect would be very lovely of the long avenue. Let me know what you think about this.”

The Washington Post continues the history, explaining that the day after Scidmore received the letter from the First Lady, “she told two Japanese acquaintances who were in Washington on business: Jokichi Takamine, the New York chemist, and Kokichi Mizumo, Japan’s consul general in New York. The two men immediately suggested a donation of 2,000 trees from Japan, specifically from its capital, Tokyo, as a gesture of friendship” and asked Scidmore to find out if the First Lady would find the gift acceptable. She did.

With First Lady Helen Taft’s support, things moved quickly. Although the first batch of cherry trees could not be planted, the second love letter from Japan arrived just in time for Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1912. Over 3,000 trees were shipped from Yokohama to Seattle, then in insulated freight cars to Washington D.C. And, on March 27, 1912, Helen Herron Taft and the Viscountess Chinda, wife of the Japanese Ambassador, planted two Yoshino cherry trees on the northern bank of the Tidal Basin.

That year, the Washington Star reported a “Washington woman who has been decorated is Miss Eliza Ruhamah Scidmore, whose home is at 1837 M Street northwest, and who in 1908 was given the cross of the Order of the Eastern Rising Sun by the Emperor of Japan in recognition of her writings on Japan.” (Author's note: Scidmore’s home appears to be standing at the address reported in 1912, a stately, restored brick Victorian, now living a new life as a restaurant.)

The National Cherry Blossom Festival reports that several years later in 1915, the United States reciprocated with a gift of flowering dogwood trees to the people of Japan. In 2012—a century after the planting of Japan’s gift of cherry trees in Washington D.C.—the United States sent 3,000 flowering dogwood trees to Japan as an anniversary gift. The dogwood trees were planted in Tohoku region of northern Japan and in Yoyogi Park of Tokyo.

To preserve the original genetic lineage of the first cherry trees, the NPS reports that “approximately 120 propagates from the surviving 1912 trees around the Tidal Basin were collected by NPS horticulturists and sent back to Japan (in 2011) to the Japan Cherry Blossom Association…Through this cycle of giving, the cherry trees continue to fulfill their role as a symbol and as an agent of friendship.”

This year in Huntington Beach, we will again plant new cherry trees in Central Park—near the lakeside Secret Garden—with the Consulate General of Japan in Los Angeles and delegates from our Sister City Anjo, Japan. This Southern California–central Japan friendship began in 1982 and is working toward its own centennial event. The Cherry Blossom Festival of 2082 will be one for the books!

Reference:

“It’s Hanami Time! Huntington Beach Cherry Blossom Festival on March 20” at Surf City Family (February 29, 2016)

The Huntington Beach Sister City organization website for the annual Cherry Blossom Festival with information on performances and vendors.

“History of the Cherry Trees” from the U.S. National Park Service

Ruane, Mike. “Cherry Blossom’s Champion, Eliza Scidmore, Led a Life of Adventure.” The Washington Post (March 13, 2012)

Zimmerman, Andrea. Eliza’s Cherry Trees: Japan’s Gift to America (The site includes more information about Eliza’s life, travels and writing, and teacher resources.)

* This article was originally published on Historic Winterburg’s blog on March 10, 2016.

© 2016 Mary Urashima