Recently, several Japanese print media outlets and blogs have featured articles on the poverty problem in Japan.1 According to analyses by experts and data compiled by aid organizations and research groups, the relative poverty rate in Japan, in other words, the proportion of people living below half the median per capita income, is one in six, giving the poverty rate at 16.1 %. Comparing the poverty rates of 30 OECD member countries, Japan ranks fourth with a high poverty rate, with Mexico at 20%, Turkey at 19%, and the United States at 17.4% (2012 statistics2 ).

A survey by the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare has set the poverty line at 1.22 million yen take-home income for a single person, 1.73 million yen for a two-person household, and 2.11 million yen for a three-person household, and many of the relative poor below this level are non-regular workers, whose numbers have been increasing for the past dozen years (38% of the relative poor, or about 20 million people, are in non-regular employment). The child poverty rate is also said to be fluctuating at around 16%. For single-mother households, the relative poverty rate is 50%. For the elderly, the rate is as high as 20% (10% in the UK and Germany, and 23% in the US), and in recent years the term "lower-income elderly3 " has emerged.

Youth poverty is not just caused by non-regular employment, but also because even after graduating from university and joining the workforce, they have to use part of their salary to repay debt for five to ten years. If they have low skills and cannot become regular employees, they will almost always belong to the low-income bracket.

According to the latest statistics, there are 1.63 million households receiving public assistance who have incomes below the poverty line, with 2.16 million people receiving assistance. Of these, half, or 800,000 households, are elderly, and the situation for elderly single-person households is extremely severe4 . Japan is also higher than the OECD average in terms of the Gini coefficient, with a figure of 0.36 (2013). Looking at these figures, it appears that Japan's poverty rate and inequality problems are worse than those of major European countries, and slightly better than those of the United States.

However, I have doubts about Japan's poverty rate when viewed from the perspective of the relative poverty rate. I often visit housing complexes and areas in Japan where foreigners live for work and for personal reasons. I also have many opportunities to visit not only Argentina, where I was born and raised, but also North America, Spain, France, and Latin America, and I try to intentionally visit immigrant neighborhoods and urban suburbs in those countries as much as possible. Although it is not possible to make a simple comparison, I cannot help but feel uncomfortable with the biased assertion that Japan's disparity is so severe that poor people cannot even live a basic life, and that many young people, elderly people, single parents, and foreign workers are homeless.

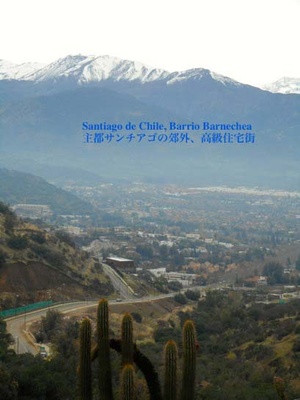

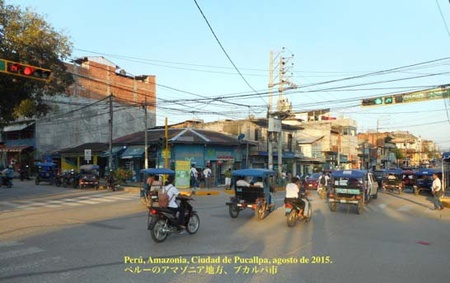

The disparity between rich and poor in South America is unimaginable, and there are many people living in absolute poverty (living on less than one dollar a day5). As a result, the places where people live, the routes they take to school and work, the shopping malls and schools they go to are all different, and in places with poor security, foreign diplomats and employees of large companies are forced to be picked up and dropped off in cars with guards. In Japan, of course, there are super expensive kindergartens, after-school care, private schools, high-rise apartments, villas and members-only clubs, but there are no places where the living environments of the wealthy are completely isolated and have heavily armed guards. When I visited Spain and France, I visited residential areas with many South American immigrants, and in some areas, you should never get off the train at a station in that area. In South America, the danger is even higher, and if you step outside the downtown area where foreign tourists are enjoying themselves, you could be attacked at any time, and there are places where you can feel a murderous aura that sends chills down your spine. That is how great the social friction and conflict caused by disparity is.

It is difficult to understand the poverty situation of each country just by looking at the figures for absolute poverty. Poverty situations must be compared while taking into account average income, the Gini coefficient (which indicates inequality), price index, inflation rate, average life expectancy, infant mortality rate, literacy rate, junior and senior high school non-enrollment rate and non-completion rate, labor productivity, industrial structure, unemployment rate, black labor rate, crime rate (general crime and drug crime war, etc.), etc. Even if Japan's relative poverty rate is high, it is hard to imagine that the poverty rate in Japan is actually higher than that of Italy or Spain6 . In particular, Japan has unique characteristics such as a high school attendance rate, a high rate of social insurance enrollment, a well-developed infrastructure, and an excellent civic spirit, which may make it difficult to compare it with other countries, especially South American countries.

When I visit public housing complexes where South American foreigners live, I see many poor elderly people and Japanese single mothers. However, this is different from the poverty I have seen in South America. Foreigners choose these complexes because they offer affordable rent, are easy to live in, and allow them to save money. It should also be remembered that without these foreigners, the residents' association and the minimum events held in the complexes would not be possible.

There are not many previous studies, but several surveys on poverty among foreigners were conducted immediately after the Lehman Shock in 20087. They emphasized that poverty is worsening due to layoffs and wage cuts caused by the economic crisis. In addition, the ratio of Peruvian and Brazilian children born out of wedlock exceeds 30%, and the hardships of life as a single mother have been pointed out. As a result, the number of people receiving welfare benefits is also increasing. However, because learning assistance and various support are provided, about 120,000 Brazilians have returned to their home countries, but many foreigners have remained in Japan. According to estimates from these surveys, the relative poverty rate of South American and Filipino nationals is about twice that of Japanese people. In addition, since they work for small and medium-sized enterprises and contract companies on a full-time contract, their wages are generally not very high. However, this situation has continued since they came to Japan, and it is unlikely to improve significantly in the future, and they accept this reality.

Paradoxically, the employment preparation training program for Japanese workers promoted by the Foreign Employment Measures Division of the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare after the Lehman Shock, and its expanded version, the Foreign Employment and Settlement Support Training Program, 9 as well as the amendment of the Worker Dispatch Law, have led to an increase in direct employment, despite the unstable nature of the employment, and the enrollment rate in social insurance (employee pension insurance and health insurance) and labor insurance (employment insurance and workers' accident compensation insurance) 10 . Multilingual consultation desks at employment offices, labor administration offices, and labor standards inspection offices are also more abundant than before. As for Japanese workers in South America, as they are increasingly settling there, they are highly conscious of enrolling in pensions, and are making the most of Japanese language training and skills training to increase the retention rate as much as possible even if wages are not increasing. Some people who receive welfare are in this situation because they have no choice, but there are also many cases where they have too much debt or have not planned their lives in a planned manner. Most people see bankruptcy as a means of dealing with debts and do not feel socially embarrassed by it.

Foreigners from developing and emerging countries come to Japan in search of a more hopeful future. It is true that in Japan, inequality has widened somewhat due to the effects of globalization, non-regular employment has increased considerably, and the country faces many contradictions and challenges amid the structural distortion of a declining birthrate and aging society.11 However, there are no societies in South America or Southeast Asia that have such well-developed infrastructure, educational opportunities, and support systems for social integration. Even with inequality and poverty, many settled foreigners see Japan as a society with many possibilities, with a level that is incomparable to their home countries. Even if it is non-regular employment, it is meaningful to have a job, and for many low-skilled foreign workers, with such a well-developed infrastructure, they can provide their children with a much better life and education than they had in their home countries.

It is impossible to make all workers full-time employees or to completely eliminate disparities, and if you accept this reality, Japan is a fairly comfortable society to live in. Foreign residents choose to live in this society based on this premise.

Notes:

1. " Child poverty: Measures tailored to local conditions " (The Nishinippon Shimbun, February 24, 2016)

Serial/Special feature " Tomorrow for Children " (The Nishinippon Shimbun)

" Poverty and Public Assistance (1) Japan has changed since the late 1990s " (yomiDr., 2015.06.19)

Nakajima, Nishizawa, Hitoshi, Special Feature "The Poverty Trap" (Weekly Toyo Keizai, April 11, 2015, pp. 38-81)

2. " Overview of the 2013 Basic Survey on National Living Conditions " (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, 2013) *Data from 2012

3. Takanori Fujita, "Lower Elderly: The Impact of the Collapse of Retirement for 100 Million People," Asahi Shinsho, 2015.

The cover of the book uses an impactful phrase: "Even if you earn 4 million yen a year, you could end up living on welfare in the future!?" The book has become a best-seller, selling 130,000 copies.

4. Statistics for December 2015, announced by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare on March 2, 2016.

" 1,634,185 households on welfare = New record as of December last year - Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare " (Jiji.com, March 2, 2016)

5. There are 1.3 billion people in the world who cannot even live the bare minimum. If we include those who earn less than $2 a year, the number rises to more than 3 billion. Half of the world is in this state of poverty.

6. According to the World Bank's Gini coefficient, Japan is 25, but compared to Argentina's 44, Mexico's 48, Chile's 52, and Brazil's 55, the difference is more than double, showing just how large the disparities are in South America. In addition, the poverty rate also differs considerably depending on whether the income of all households is measured in five or ten classes, as the income ratio between the richest and poorest classes.

7. Yukiko Omagari, Sachiko Takatani, Naoto Higuchi, Itaru Kaji, Nanako Inaba, "Advocacy on 'Migrants and Poverty'," Multilingual and Multicultural Studies: Practice and Research, Vol. 4, December 2012.

Takashi Miyajima, "The Triple Deprivation of Foreign Children," Ohara Journal of Social Problem Studies No. 657, July 2013

8. " Employment Measures for Foreigners " (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, Foreign Employment Measures Division)

9. The Japan International Cooperation Center (JICE) is actually implementing this project. (" Project Overview ")

10. " Press Releases on the Employment Status of Foreign Nationals (2003-2006) " (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare)

11. Even if we look at the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare's income distribution survey and the National Tax Agency's private sector salary survey, even though the gap has widened, people with salary incomes of over 8 million yen are only around 3%, those with incomes of 10 to 15 million yen are around 4%, and those with incomes above that are around 1%. It is true that the construction of tower apartments for high-income earners has increased, but the overall ratio is low, and households who purchase such homes are heavily burdened with loans. In Japan, the gap has been largely rectified through income tax, inheritance tax, etc. In South American countries, there is almost no inheritance tax, and the rate of tax evasion on income tax and corporate tax is as high as half.

© 2016 Alberto J. Matsumoto