In Yumi Sakugawa’s breakout comic, I Think I Am in Friend-Love with You, a one-eyed monster pines for a faceless creature. The pair look something like Cousin It and a soft-bodied Stormtrooper—ageless, genderless, of unrecognizable species—but their story resonated with readers around the world, so much so that the free webcomic was republished in hardcover form.

Since that first book came out in 2013, Sakugawa has contributed comics to sites, including The Rumpus, and self-published several zines, two of which were compiled into a second book, called Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe, in 2014. A sequel, There is No Right Way to Meditate: And Other Lessons (Adams Media), will be available on November 1, 2015 and, if you live near Los Angeles, you can catch Sakugawa reading from it the following day at Skylight Books.

In the meantime, though, the cartoonist has yet another book, just released on September 19th. Named for the traditional Japanese art of flower arrangement, Ikebana (Retrofit Comics) follows art student Cassie Hamasaki as she presents her thesis: a performance piece in which she turns herself into a human embodiment of ikebana, dressed in nothing but her underwear and a handful of foliage.

I met up with Sakugawa at Chimney Coffee House in LA’s Chinatown to chat with her about her work, Spam musubi-eating monsters, and the power of silence.

* * * * *

The Rumpus: What inspired Ikebana?

Yumi Sakugawa: I was an art student at UCLA and, to be honest, I wasn’t a very good art student, especially toward the end. I had such a hard time imagining myself pursuing the fine-art path that was expected of us, where we would go to graduate school and then show our artwork in very respected institutions like MOCA or The Whitney and teach art in university settings. I just didn’t really see myself doing that, but I wasn’t sure what to do. So it is sort of loosely based on my art school experiences, and where I was in my early twenties. I struggled a lot with defining for myself what art is, what is meaningful art practice for me. Making the comic was my own way of trying to answer that question for myself.

The interesting thing is that actually when I first came up with the story, I didn’t even have ikebana in mind. It was just that this girl was a sort of moving performance piece that went from the classroom to the city, and you could actually hear her internal dialogue as she went about this performance. It wasn’t until the third or fourth or fifth draft when it finally sort of dawned on me, oh, she embodies an ikebana piece. Once I figured that out, that was when the story really started falling into place.

Rumpus: Why ikebana?

Sakugawa: I just originally had her wearing organic items on herself, so from there—I don’t even know how ikebana came about but—once I made the connection that maybe she could be a physical embodiment of ikebana, then I drew back on my own memories of seeing ikebana arrangements at the Japanese American Cultural Center. And also, when I was teaching English in Japan, I had some adult students who would do ikebana as a fun pastime, so I think it was already in my subconscious, and when I started looking into the history of ikebana, it became more intriguing for me as a backdrop for the story.

Rumpus: It took me a long time to notice that the professor was an orange. I didn’t notice that until the second time I read it. And then one of the students is a cat. How did you settle on those classroom demographics, of having some humans and some creatures?

Sakugawa: Well, it’s funny, even when I was doing initial drawings for Ikebana, the professor character was always this weird, amorphous, sort-of-male character that wasn’t completely human. And I think sometimes I like to randomly turn people into non-human characters because I feel like if I were to draw them as humans, it would just read as a very well-tread trope of, say, “oh, a pretentious art professor.” I feel like I see that character so much, so turning him into an orange is sort of my way of making it more interesting for me. Also, I think to show that he’s a doofus but without relying on visual cues that would show him as this overly liberal, white professor who is really into himself.

Rumpus: When did you start making comics?

Sakugawa: I’ve always made up stories and drawn them since I was a kid. I remember making comics about classmates or about friends or just making really snarky, sarcastic comics in high school, but it was always just something I did on the side, something I never thought about too seriously. I think it was in college when I was introduced to indie comics and the wide scope of that realm and saw that I didn’t have to box myself into this DC-Marvel or manga style binary.

Rumpus: So was your style more like that before? Like traditional comics?

Sakugawa: Yes and no. I definitely did a lot of imitation art, of Sailor Moon especially. I didn’t really read DC-Marvel comics. I guess I always had the idea to do comics more in the indie comic realm, but I just didn’t have the vocabulary or the knowledge that that audience or that scene even existed, so I felt like it was a matter of just getting exposure to it that really led me want to pursue it more.

Rumpus: What were some of those indie comics that really inspired you back then?

Sakugawa: Well, I think one of the first indie comic book artists that really resonated with me was actually a Japanese American indie cartoonist, Adrian Tomine. I came across his Optic Nerve comics. I feel like his storytelling style, his visual style, they were my first early influences. The one indie comic book that sort of turned a switch in my brain was probably Blankets by Craig Thompson. I also read Black Hole by Charles Burns, and then I also lived really close to the Giant Robot art store, so I would also just go there a lot and look through their mini comics and indie comic collections, which sort of was my informal comics education during college.

Rumpus: Has your style evolved a lot over time?

Sakugawa: Yeah, definitely. I think in the beginning I tried to ape the tighter linework that my early influencers had, like Adrian Tomine or Craig Thompson, but I quickly realized that that wasn’t my style, so I think especially in more recent years, my style has gotten a lot looser. I do really like not having to labor too much over my art. (Laughs) I sort of embrace the fact that I’m not a very detail-oriented person. I like to make as little linework as possible to convey as much information as possible.

Rumpus: I remember hearing about you for the first time when I Think I Am in Friend-Love with You blew up in 2013. Was that the first time you got such a big reaction?

Sakugawa: Yes.

Rumpus: How did that feel? What was it like?

Sakugawa: It came out of left field. It was really unexpected. I was just so blown away that a little six-page comic I posted online for free struck such a chord with everyone, and looking back on it now, I really owe it to that event for kickstarting my career and taking my comic book art to a whole other level of exposure.

Rumpus: I think part of what makes it so appealing is that little monster. I read that you wrote that comic out of a feeling of losing touch with college friends and trying to catch up with them again, and I can definitely relate to that, especially having gone to college far away. But what made you decide to pair that with that little monster rather than a person, and how did you settle on his design?

Sakugawa: I always feel like if I drew that character as someone that looked like me, an Asian American college girl wearing emo clothes, platonically pursuing this other college guy or girl or what have you, that would have restrained the story to a very specific, autobiographical context, where it’s more about me and less about the feeling. I think ultimately I wanted to take those autobiographical elements away to focus on the feeling itself as a way to dive deeper into what I was feeling, and I think, generally speaking, with my stories, I like the idea of stripping away gender, age, ethnic identifiers so that readers have more blank spaces, blank, neutral spaces, they can fill themselves into. With Ikebana, it was more consciously nearing my own art school experiences, so I felt like it made more sense in the story to have mostly human characters and a main female protagonist, and not this weird one-eyed monster creature.

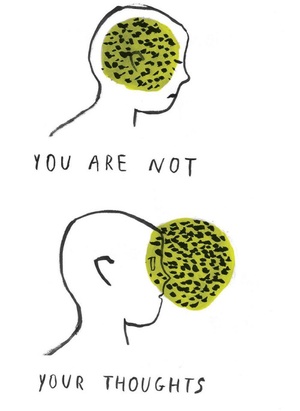

Rumpus: I remember seeing one of your drawings that was a message to artists: “Start with a feeling, and then put it out there and see if others feel similarly.” I might be totally butchering it, but I really liked that sentiment. Is that why you draw monsters so often, because they’re a little more abstract and easy for people to put different individual experiences into?

Sakugawa: I think so, and I feel like it just makes so much sense why in so much children’s programming—Sesame Street or The Muppets—the characters are all human-like but also very monster-like or fantastical, and I think kids need that neutral space. Adults too need that neutral space where in making characters so weird-looking, it makes them more universal, so I’m always interested in exploring that.

Rumpus: In Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe, you go back and forth between using those monsters and using people. Page to page, what made you decide which one to use and what type of features for this monster to have, and monsters versus bunnies and all of that?

Sakugawa: I feel like it’s never too deliberate or too conscious a decision what characters I decide to do. Definitely these days, I’m drawn to bunnies. It’s sort of my way of remembering how obsessed I was with bunnies as a kid and how I had a pet bunny. I’ve always been drawn to how innocent yet how strong they are, as animals and as mythical creatures. And as for the comics in Your Illustrated Guide to Becoming One with the Universe, a lot of the comics were actually individual blog entries posted over time that just happened to end up in a collection together. But with every individual comic, they just sort of came up depending on whatever mood I was feeling. That’s basically it.

Rumpus: A lot of your characters don’t talk in speech bubbles, and some, like Cassie in Ikebana, don’t even talk at all. What is the thought process behind that?

Sakugawa: I think that I like the idea of characters not talking, like with my Friend-Love character or with my more recent bunny characters, because I like the idea of constraining their mode of conversation, so as a viewer you have to maybe work a little harder to figure out what their inner state is. And also, for me as a creator, I don’t have this verbal crutch to tell readers what the character is going through. So in Friend-Love, it was actually really fun for me to not have a character’s mouth—and for the character to have just one eyeball—so that if the character was feeling sad, I would draw the eyeball a little sadder (laughs), sort of figuring out how to make a single eyeball look happy or sad or how the body language conveys what the character is feeling. And I think it also comes from my own personal bias of being drawn to people who don’t talk much, like there’s just more real or imagined mystery to people who say less, so I sort of take it to an extreme by imposing the limitation of them not talking at all.

Rumpus: When you’re drawing these characters and you’re trying to convey a feeling, do you do much research or draw from photographs to get their movement or posture?

Sakugawa: For human characters, yes, I would look—I would take pictures of myself or ask my boyfriend to pose for me. But for the more animal-like creatures, I just sort of make them up in my head. Again, I think there’s this sort of inherent laziness in me where I don’t want to labor too much on proper anatomy, so I sort of gravitate towards drawing more pliable, round characters that are more stuffed-animal-like than human-like. Less joints to worry about, essentially.

Rumpus: More fur to cover everything up.

Sakugawa: Exactly!

Rumpus: When you were a kid, what came first for you, writing or drawing?

Sakugawa: Drawing.

Rumpus: How did that start? I mean, I know most kids draw, but what kinds of things did you like to draw back then? When did it feel like it was a thing that you really had to do?

Sakugawa: I drew a lot of bunnies, with crayons. I drew monsters or people, friends. One of my childhood friends, she uncovered this drawing I did when I was nine years old. I drew all of the people in our circle of friends as cats. They’re wearing t-shirts and shorts, but they’re all in cat form. It probably wasn’t until I was maybe nine or ten years old where I felt like it was a skill that I wanted to keep doing, as opposed to just one of the many activities that all kids do.

Rumpus: Did you grow up in a very artistic family?

Sakugawa: No. I mean, my parents, they were never against me pursuing creative things, but I don’t think they necessarily were consciously fostering it. I guess the best thing they did was that they just sort of let me do whatever I wanted. But neither of my parents particularly like to do creative things as far as writing or drawing goes. I keep hearing that my grandmother was drawing when she was younger, but other than that, I feel like my desire to make art, it kind of came out of nowhere. And maybe it came out of also me being a very introverted, shy person. So I read a lot of books and maybe that fed my imagination.

Rumpus: You grew up in Orange County, but both your parents are from Japan. Did you go there a lot as a kid?

Sakugawa: I did. I probably went five or six times during my childhood, up until high school. Most of my relatives are in Japan, basically. I haven’t been back in about over seven years now, but I think every time I go to Japan, it feels like going home in some way, even though it’s not the country I was born in. Even though I’m not the most proficient at Japanese, it’ll always be a very familiar, internal language to me over English. I definitely don’t ever want to live there full-time.

Rumpus: Why not?

Sakugawa: Well, I feel like, one, I’m too Americanized in my way of thinking to feel like I would really fit into Japan. Also, I just feel like my Japanese language skills aren’t good enough to, say, work in a Japanese work environment, and I really don’t want to teach English again. (Laughs) I did that once.

Rumpus: How was it?

Sakugawa: You know, I wasn’t very good at it, so I’m okay not doing it again. I think it’s just always that struggle between the more individualistic attitude of Americans versus the more community-oriented attitude of Japan. There are definitely pluses and minuses to both worldviews, but I just feel like I see myself just struggling with fitting into Japanese society.

Rumpus: When you are there, do people usually assume that you are from Japan, or can they tell that you are American and treat you like you’re American?

Sakugawa: When I was in Japan for a year, the last time I was there and I was teaching English, towards the end, my Japanese actually improved a lot, so I was able to pass as a Japanese person. But I feel like if I were to go there right this moment, I think people could tell by the clothes I wear, even the way I carry myself, I think. It’s like how when we see European tourists, you know—

Rumpus: You can tell from their shoes—

Sakugawa: Exactly! You can just instantly tell.

*This article was originally published on The Rumpus on September 18, 2015.

© 2015 Mia Nakaji Monnier