The first mass migration to the East Coast?

The southern Atlantic states that "The Centennial History" introduces in Chapter 25 are Georgia, North Carolina, and South Carolina.

According to statistics, the Japanese population in Georgia was 1 in 1900, 9 in 1910, 32, 31, 128 in each decade thereafter, and 885 in 1960. Prior to these statistics, there is the following "legend" about the first Japanese to set foot in the state, who were "the first group of immigrants on the East Coast."

"Around the 1880s, a British man named Frank Aiken traded with the Orient from Savannah Port, mainly traveling back and forth to Shanghai. When the black slaves he had been using were freed, he brought over 20 people from Kochi Prefecture in Japan to supplement his workforce and engage in rice farming on the outskirts of Brunswick. This is said to be the first mass immigration of Japanese people to the east coast... They all endured for four or five years before returning home, and one of them, a certain Sawada, is said to have sent Christmas cards to them for many years to come."

Chop suey restaurant in Atlanta

In the state capital of Atlanta, a Japanese man named Abe opened a chop suey restaurant around 1920. He is said to be the first Japanese person to operate in the city, and there is an interesting story about Abe.

"In 1923, this Abe shot at several white people who had robbed his store from the second floor with a pistol, hitting one and killing him instantly. As a result, people of color were in a bad position at the time and his case went to a disadvantage in court, so at the urging of his lawyer, Abe fled to Miami, where he later died of an illness."

In addition, Yoshinuma Teijiro, originally from Tokyo, and Matsunaga Shiro, originally from Kumamoto, opened chop suey restaurants in Atlanta and made them successful. Yoshinuma ran a large-scale business from around 1923 until the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, and his restaurant became a famous attraction in the town, and he had friendships with influential Americans in the city.

Matsunaga emigrated from Miami, Florida in 1928 and continued to operate the store until the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States. He voluntarily closed the store, but reopened it after the war.

Other than these, there were five or six Japanese students studying at Emory University in the city at any one time, from early on, in the religious and medical departments. After the war, some people opened up forests and successfully cultivated crops in greenhouses.

After the war, in 1946, the Furukawa Frank family, who had learned chick sorting techniques in Denver, moved to Avandale, a suburb of Denver, and ran a successful chicken farm.

Among these stories of successful people, one man who receives special treatment is Butsuen Sachihiko. "Centennial History" introduces the activities of Japanese Americans in each state, and after immigration, many Japanese moved around the United States in search of better opportunities or due to business failures or other circumstances. In the case of the West Coast, the war had a major impact on these relocations.

Success in interstate farming business

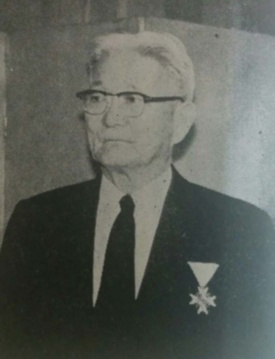

In particular, people who have been successful in business or who have business interests across a wide area often appear in the history of the Centennial of America, across states. Yukihiko Butsuen is a prime example of this. He was described as "a pioneer whose life was so eventful that there was almost no state in America that did not bear witness to his footsteps," and he managed farms across a wide area and held important positions in the Japanese Association. He also worked hard to establish the Immigration and Naturalization Act, for which he received a reward from the Japanese government.

His life and work are covered in considerable detail in the Georgia Journal.

Born on January 1, 1887 in Kumano-cho, Aki-gun, Hiroshima Prefecture, Butsetsuen moved to San Francisco in 1906, and then to Portland, Oregon. His initial settlement ventures were unsuccessful, but he managed Japanese workers in a coal mine in Wyoming, and was contracted for development work in Colorado. From 1920, he cultivated potatoes, corn, wheat, and other crops in Iowa, and also cultivated onions 400 miles away in Minnesota, while also growing vegetables in Indiana, thus running a farm business across three states. During this time, he and a friend founded the Japanese Agricultural Products Company in Chicago, and were involved in agricultural product brokerage.

In 1931, they moved to Brunswick, Georgia, where they began growing lettuce in partnership and continued to operate a large-scale farm after the war. The farm was located in White Oak in the southern part of the state and was called Merrifield Plantation.

Initially it was jointly run by Butsuen and Omae Ichiro, a native of Hyogo Prefecture, but after the war, the family of Ozaki Tonan and others joined in, and it became a base for Japanese people on the Atlantic coast of Georgia and also gained a reputation among Americans.

Butsuen also had political power, and once when a Japanese man was sentenced to death for killing another Japanese in a gambling fight in a coal mine in Wyoming, he met with the governor and had the man released on condition that he be given two years' supervision.

Prepared to die as a Japanese

The number of Japanese people in both North Carolina and South Carolina was small before the war, with statistics showing "2 and 8" in 1910, and then "24 and 15," "17 and 15," "21 and 33" in each of the following ten years, before increasing sharply after the war to 1,265 and 460 in 1960.

The Centennial History gives a detailed introduction to one Japanese person in South Carolina, where racial prejudice is strong. The person is Tokunaga Mitsuo, who was born in Nagasaki Prefecture. He came to the United States in 1909 and went to Columbia, the capital of South Carolina, where he has since settled. He is said to be the first Japanese person in the state.

Tokunaga got a job in a greenhouse for growing flowers and worked there for many years. In 1914, he married a German woman and had two children. Although life was hard, he was a hard worker and earned the trust of his neighbors. The story of his life from then until he became independent is fondly described in the Centennial History.

"While thinking about starting an independent business, he came across a greenhouse for sale, but had no capital. So he went to the bank to get a loan, and when he was asked what he had as collateral, he had no choice but to answer that he had nothing except his wife and two children. The bank cashier said that he normally wouldn't lend him money, but he gave him the large sum of $1,200. Although he was penniless with his wife and three children, the cashier had seen and heard about Tokunaga Mitsuo's honesty and hard work, and thanks to his wise decision, Tokunaga now owns 15 acres of land, 29 greenhouses in three locations, and three flower shops in the city..."

Tokunaga was a successful man in America, but he never became a naturalized citizen, saying, "I will die after shouting 'Long live the Emperor' three times." He was also scheduled to be honored at the 100th anniversary of the establishment of friendly relations between the United States and Japan, but he declined, saying, "I have done nothing for Japan that would merit an award."

(Note: I have used the original text as much as possible, but have made some edits. Titles have been omitted.)

*Next time we will introduce "Japanese people in Florida."

© 2015 Ryusuke Kawai