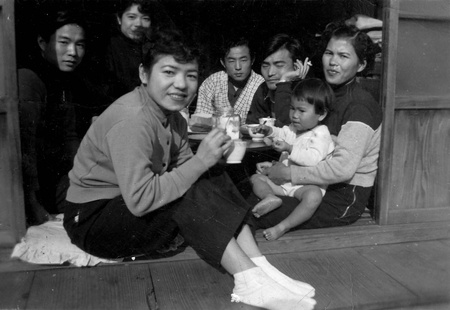

With an infectious smile, Junko Uehara escapes from her Fujinkai choir class for a few minutes. It was just for a few minutes, to take photos for the article. “My mother doesn't like missing her classes,” says her daughter Ana.

But sometimes, reliving memories with family is enough to escape from our obligations and passions for a little while. Junko had escaped for only a few minutes, but without realizing it, it ended up being almost three hours, between memories and anecdotes together with her daughter Ana and her granddaughter Fabiana.

At 86 years old, Junko Uehara remembers the essence of each experience, although sometimes the details escape her mind.

WAR TIME

Junko was born in Shuri, the former capital of Okinawa. She proudly says that her parents were jyogakkou teachers (“school for women”, equivalent to high school, according to the old pre-war Japanese educational system). Junko was able to attend school and did not have to work on the farm, as many girls her age did. But he was barely in his second year of jyogakkou when the war came to change everything.

Schools stopped working and people were already beginning to evacuate. Junko remembers: “That's when the war started. The Americans were going to come to Okinawa. Children under 15, ojiichan, obaachan or elderly dad could go somewhere else. To Kumamoto, Kagoshima, Miyazaki, somewhere else.”

Those who stayed on Okinawa were mostly the students who exchanged books and notebooks for weapons and bandages. Many boys became soldiers and girls became nurses. Junko's companions in more advanced grades were the Himeyuri, the war nursing corps. But Junko was lucky. He escaped from Okinawa with his mother and three younger brothers. His father had already passed away by then.

Junko remembers that, along with other evacuees, they boarded a warship that would take them to Kumamoto: “We took all the things we could carry: clothes, pot. Sometimes I went up (to the deck of the ship) and there was quite a bit of sun. He slept there. I saw American planes approaching to bomb. “I was afraid of that, but happily nothing happened.”

They arrived in Kagoshima and were transferred by train to Kumamoto. Junko was already about 15 years old.

They were evacuated to a temple. There was no other place. “All of us Uchinanchu were together. They made us sleep in a temple. When he woke up at night, there were quite a few ihai (funerary tablets), also a sitting Hotokesama (Buddha). I looked at that and I was afraid. The government gave food to everyone: rice, sweet potatoes, vegetables. To cook, I had to go outside the temple. There was that thing that you played 'bong', 'bong', that was taken out, and a stone was put there. Each one put a pot and everyone cooked. There was no firewood, the three of them (her brothers) had to go and bring firewood,” Junko recalls, almost laughing, as if she were telling an anecdote.

This was the life of Junko and her family for almost two years. Then, they had to evacuate to a safer, more remote place or “more inaka ” as Junko says, where the war was barely felt.

It was 1945 when the war ended. Some time later, all the evacuees returned to Okinawa, including Junko's family.

RETURNING TO OKINAWA

Okinawa was no longer the same as they left, everything had changed. There were no Japanese ships, but there were American ones. His house was gone. Almost everything had been bombed. They lost some family members during the war. Only the shadow of death and destruction remained on Okinawa.

But life continued. Junko worked as a children's teacher and later went to work in the Okinawa kencho (prefectural government headquarters).

“And do you remember when you met your husband?” is the question that makes her blush. With a knowing chuckle between his daughter and granddaughter, he tells me that he doesn't remember much.

Ana, her daughter, helps her a little. “My mom married my dad (Ryowa Uehara) in 1953, eight years after the war ended.”

That was enough for Junko to remember more. “Oh, yes, I remember. “I got married in Okinawa,” he says. "One of my mother's friends was a sanbasan (midwife) and my mother told her: 'My daughter is still single, she is not getting married.' One day, I went to visit mom's friend, the sanbasan . She quickly sent for Ryowa, who was a teacher at the school that was nearby. Right there, we both talked: 'Yoroshiku onegaishimasu' (nice to meet you). That is how I have known him.”

She still tells it as if it were yesterday, with that shyness of a newly in love, bowing her head from time to time, but never losing her smile.

Ana remembers that her father was born in Peru, but was taken to Okinawa when he was little. It was the time of the kirai nisei , the children of Japanese born in Peru and who were taken to Japan to study. Ryowa was one of them and spent his childhood and part of his youth in Okinawa, until he met Junko.

Ryowa wanted his family in Peru to meet his new wife Junko and his little daughter Ana, who was 1 year and 9 months old at the time. Junko left everything in Okinawa and followed her husband.

LIFE IN PERU, FAMILY LIFE

In 1955, Junko arrived in Peru for the first time. Although she was a newlywed with a little girl in a strange country, she had no problems. Her father-in-law Ryosuke, Ryowa's father, already had his own business in Peru, where they could live and work.

“It was a fine, high-class restaurant. It was July 28th. The waiters had white shirts, black pants and michi ties,” Junko says nostalgically. It was there where he learned Spanish together with Ana.

At first it was difficult, I barely understood the language. Junko remembers the day the cook greeted her with “Good morning, ma’am.” but she did not answer. “I thought I was speaking plainly,” he tells me. But over time he realized that it was a misunderstanding and now he remembers it as just another anecdote.

He could barely converse with his daughter Ana. Junko was conversing in Uchinaguchi (Okinawa language) with her in-laws and her husband. With her sisters-in-law and Ana, in Spanish, although she tells me that she didn't speak it well.

As she grew older, Ana spoke more Spanish and barely any Japanese. Ana remembers that that was why she spent more time with her aunts, who were Nisei. But he emphasizes to me that his mother was loving, that she showed her affection in her own way. “My mother was like the Issei of her time. They were submissive and hardly expressed what they felt. They were not about hugging or showering their children with kisses. When something needed to be corrected, my mom was like my dad, they were straight. But we never lacked anything at home, food or studies. He always advised us and told us that the family always has to be united. I think that was his way of telling us that he loved us. It's something that you already feel, it's like a connection between the two and it doesn't need to be said. But with my daughters, it's different, I express my feelings, I hug them, I hug them."

A sudden laugh between the three ends up confirming it for me.

In 1957 they closed the restaurant in search of new directions. The Ueharas moved to La Parada, where they opened another restaurant, a bazaar and even a hotel, which they named “Los Diamantes.” Their main clientele were market merchants and suppliers.

Her husband Ryowa dedicated himself to the family business, but also to the associations in which he actively participated, such as the Okinawan Association of Peru and Yonabaru Chojinkai of Peru. Junko, on the other hand, only participated in some performances, walks, and the tanomoshi they organized. Most of the time he stayed at home. “There was no time to go. I worked and took care of the children. And at night, I waited for my husband to return home. “I was stuck in the chojinkai .”

NOTHING IS THROWN AWAY

Fabiana, one of Junko's granddaughters, remembers: “Until I was 10 years old I was helping in the stores. My mother took me to visit my aunts, who lived in the back room of the business. We all had lunch together and then we went to the bazaar, where we helped a little.”

Fabiana did not live in Oba Junko's house. Since she was little she lived with the oji Inamine. “There were like 10 of us.” Fabiana remembers: “I lived with my oji on my dad's side, my dad, my mom, my sisters and my cousins on Inamine's side. We would visit the oba 's (Junko) house on weekends. But actually, I spent more time with my mom. “She is more open.”

Ana remembers her time as a student at Santa Rosa and Mercedes Cabello, during the Velasco government. “At that time there was a lot of nihonjin in (national) schools and the difference between home and school was not felt,” says Ana.

Fabiana interrupts her: “And he put me in a Peruvian-American school. I remember that there were only one or two Nikkei in the entire room. Then I entered the IPAE. But I do remember some things they taught me at home, like recycling.”

And like a ping pong of memories between Ana and Fabiana, Ana answers: “That's what I told you, that when you eat, don't leave anything behind. It's ' mottainai', throwing things away.” Fabiana: “Ah, yes… The food is not thrown away, it is left, because if not, Kamisama will punish you.” Laughter is heard again.

Fabiana is more relaxed, but she fondly remembers the oba customs that she learned as a child. Administrator by profession and mother by vocation, she still puts into practice what her mother and her oba taught her. Now it is the turn of Hiroyuki, her 6-year-old son and Ana's only grandson, to whom Fabiana instills some of these values: “Work hard,” “not waste anything” (“mottainai”) and “have quality of family life.” ”.

“Yes, my mother was a good job,” Ana adds enthusiastically, “she taught us a lot about saving. Nothing should be wasted. You have to use things to the minimum, as they say, “mottainai” and that habit kind of sticks with you, right?” Fabiana interrupts her: “And so far he recycles!” They both die of laughter.

In a more reflective and even nostalgic voice, Ana continues: “Because of work, sometimes we don't have time to meet every day, like before. When there is something to celebrate, we prepare something nice with the family. We never lose contact. It's a custom we've had since we had the store. Although we worked a lot, we always took time to have lunch together.” Fabiana nods her head and Junko just smiles.

I think it's time to end the interview. Junko realizes that she has already finished her choir classes. But it was well worth it. It was an afternoon of family memories that he shared with his daughter Ana and his granddaughter Fabiana.

* This article is published thanks to the agreement between the Peruvian Japanese Association (APJ) and the Discover Nikkei Project. Article originally published in Kaikan magazine No. 98, and adapted for Discover Nikkei.

© 2015 Texto: Asociación Peruano Japonesa; © Fotos: APJ/Óscar Chambi, Yonabaru Chojinkai Perú