With a few exceptions, the "Centennial History" devotes few pages to Japanese Americans in the central, eastern, and southern states of the United States, but New York State, home to the large city of New York, is an exception, with 50 pages, including advertisements, summarizing their footsteps and activities.

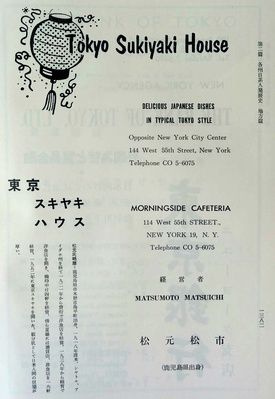

It is also the economic center of the city, and is lavishly decorated with advertisements from Japanese companies and stores, including banks, trading companies, transport companies, securities companies, and restaurants, such as Ajinomoto, Itochu America, Inc., Mitsui O.S.K. Lines, Ltd., Saito Japanese Cuisine, and Takashimaya, to name a few.

Looking only at the census, the population of Japanese people in New York State rose to 350 in 1900, 1,247 in 1910, and 2,686 in 1920. There has not been much change since then, but after the war, there was a rapid increase from 3,893 in 1950 to 8,702 in 1960.

The "Centennial History" begins with a summary of that history titled "The History of the Japanese in New York." Below is an outline of the history.

First of all, as for Japanese pioneers, in 1860, Niimi Buzennokami and his party traveled to the United States to negotiate the ratification of the Treaty of Amity and stayed in New York for a while. Nagasawa Tei, who visited Thomas Lake Harris, who was running a small farm in the suburbs of New York, from the UK around 1866, is also considered to be one of the forerunners among Japanese who set foot on New York soil.

The consulate was opened in 1872 (Meiji 5) with Tetsunosuke Tomita as its first consul.

In the commercial field, Morimura Yutaka and others came to New York in March 1876, guided by Sato Hyakutaro of Boston Institute of Technology. Sato and Morimura opened a raw silk trading business. In 1880, the Yokohama Specie Bank opened a branch there, and in 1882, Mitsui & Co. opened a branch there.

Trading businesses and raw silk dealers were prominent, but in 1902, Kushibiki Yujin, known as the "King of Expositions," rented the entire rooftop of a large building in Madison Square Garden and opened a Japanese-style park.

The Japanese community also gradually developed, and in 1907 the Japanese Mutual Aid Association was established as a full-fledged Japanese organization, and in 1912 the New York Japanese Cemetery in Masbeth, Long Island, New York was purchased.

In 1905, the Japan Club was established as a social institution. Its founders were Takamine Jokichi and others, and later a large dining hall and golf driving range were added to the club building. As for newspapers and magazines, the "Nichibei Shuho Sha" was launched in 1900 by Hoshi Ichi, Fukutomi Masatoshi and others, and the "New York Shimpo" was launched in 1911.

Among the early Japanese, Ryoichiro Arai, Hideyo Noguchi, and Jokichi Takamine are introduced as "three representative figures." Arai was a pioneer of the Japanese raw silk trade who traveled to North America at the age of 20, and it has even been said that Arai's history is the history of raw silk.

In addition to these, the book also includes summaries on topics such as "The Development of Japan-US Trade," "The Sino-Japanese Incident and the Mood in the United States," and "The New York World's Fair."

The outbreak of war between Japan and the United States and national diplomacy

The "Centennial History" provides detailed descriptions of the impact that the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States had on the Japanese community in New York and the community's reaction.

Permanent residents based in the United States found themselves in a particularly difficult position, which gave rise to a movement among intellectuals known as "people's diplomacy."

"In essence, it called for Japanese Americans to abandon their previous policy of dependence on the Japanese government, and, based on their awareness that they were part of American democracy as permanent residents, they should dispel Americans' suspicions about Japanese Americans."

They then organized the "Committee for the Protection of the Japanese in the Eastern Region" and published a statement to the Americans outlining their views. They stated that the policies of the Japanese government had nothing to do with them, and that they were loyal to the American government and democracy. In response, they received letters of encouragement from important American figures.

However, soon after the outbreak of the war, the FBI arrested more than 100 Japanese in New York on the night of December 7 and 8. The following weeks were filled with anxiety and confusion.

On the other hand, the book describes the "generous actions of the U.S. authorities" and the attitude of the general public towards Japanese Americans. It states that "Contrary to expectations, the attitude of Americans was calm." However, there were also cases where people died after being punched in an argument at a bar, or shot to death in their own homes.

During the war, the Japan-US Democratic Committee, which was established by reorganizing the "Committee for the Protection of Eastern Japanese People," was very active among Japanese people in New York. While denouncing the Japanese military and pledging loyalty to the United States, the committee also sought to improve the position of Japanese people by collecting wartime donations.

He also guided and entertained Japanese-American soldiers who visited New York. He frequently held rallies to help Americans recognize the existence of democratic forces in Japan and that there were organizations of Japanese-Americans who believed in democracy.

Many foreigners, including Miss Pearl Buck, participated in this event, and "the audience of over 300 Japanese and white people who defended the position of democratic Japanese Americans exceeded 300 people, and it was surprising to see such a large number of people attend a meeting organized by Japanese Americans so soon after the outbreak of the war." The conference was held even after the war, raising the voices calling for "an independent and free Japan."

Other activities of the Japan-US Democratic Committee included providing support to people relocating to New York, conducting educational programs for democratic education, and publishing publications.

Although it was not an organization organized by Japanese Americans, the New York Board of Education was an organization that rescued Japanese people who did not engage in anti-American activities and worked for the welfare of Japanese Americans from immediately after the outbreak of the war. They provided relief for Japanese Americans in need.

Other active groups included the New York Church, the Christian Congregation, the Methodist Church, the Young Men's Christian League, and the New York Buddhist Church.

The relocation of Japanese Americans did not go smoothly at first. One of the reasons was that the people in the camps were overly afraid of the outside world. Several problems also arose surrounding the relocation. In Brooklyn, New York, there was opposition from neighbors to the house that was being rented as accommodation for the relocated people. Reasons included that having a large number of Japanese Americans living there would lower land prices.

However, overall relocation was progressing smoothly, and there was active movement and opinion strongly defending Japanese Americans.

Hiroshima Maidens

From August 1947, limited private trade between Japan and the United States was permitted, and gradually Japanese banks and trading companies established offices in New York, exceeding 40 by the beginning of 1952. Shipping operations were also revived, as were the Japanese Chamber of Commerce and the Japan Club.

Other symbolic events included the founding of the 442nd Regimental Unit, a Japanese American unit formed during World War II, and the visit of the "Hiroshima Maidens," Japanese women who were victims of the atomic bomb, to New York City.

"In May 1955, 25 young girls from Hiroshima who bore painful scars on their faces, hands, and other parts of their bodies from the atomic bomb came to our city for surgery at Mount Sinai Hospital... The operations went smoothly, and nine of them returned to Japan in May 1956 looking completely different from when they arrived, and the rest of them also returned one after another to their hometowns."

(Note: I have used the original text as much as possible, but have made some edits. Titles have been omitted.)

*In the next issue, we will introduce " Japanese Americans in New Jersey and the New England States ."

© 2015 Ryusuke Kawai