That's right. As Aoki Sachiko wrote on the cover of the previous issue (Children and Books No. 136), the Japanese Americans who left the internment camps kept their wounds from anyone for a long time. The Japanese Americans had done nothing wrong, but the fact that they were put in the camps made them feel shame and guilt, thinking that they might have done something wrong. They were worried that by talking about it, the anger and pain they had buried deep inside would come spilling out. They resigned themselves to the fact that what's done is done, that there was nothing that could be done. They spent their days doing all they could just feed their children, and couldn't think about anything else.

Professor Tetsuden Kashima of the University of Washington calls this feeling "social amnesia," and goes on to explain it as follows: It is not a mental illness, but a collective phenomenon of consciously suppressing emotions and memories of certain events. They consciously avoided touching on their imprisonment and the issues that had left rifts in their community. They did not completely forget, nor did they bury it in the depths of their consciousness, to the point that they needed the help of a psychiatrist to bring it back. They would sometimes talk about trivial or humorous details from their time in the camps with fellow experiencers, but they never delved deeper than that. 1

Estelle Ishigo, who was writing about her experiences in the internment camp, saw this just before leaving Heart Mountain: "An old man went to a field and let a little bird out of its cage, setting it free. The little bird spread its wings into the vast, open sky. It tried to fly with all its might, but it could hardly fly at all, fell quietly to the ground, and lay there dead." 2 Were the Japanese-Americans who left the internment camps actually able to fly?

* * * * *

Tetsuden Kashima argues that whenever a major event occurs, society disrupts its old customs, and in order to cope with the event, new customs are integrated into old ones, undergoing repeated change. As for Japanese people, they have undergone major events, such as the period of critical adjustment when they immigrated from Japan, the period of anti-Japanese sentiment in the early 20th century, the period of adaptation that followed, the sudden internment after the outbreak of war, and the current period of readjustment of their lives, followed by the movement for apology and compensation, and both Japanese society and their ethnic identity as Japanese people have undergone change. 3

Starting anew may sound like a bright idea, but that was not the case at all. Kashima also shares an anecdote from Daniel Okimoto's time: "We put our hands in the rice bin and found nothing... Sometimes we heard a knock on the door, and when we answered, we found bags of groceries and hot food waiting for us. My mother said it was God's work, but if that was the case, God's messenger must have been a kind-hearted Japanese friend who had heard of our plight." 4

1. Rebuilding lives during a crisis < From 1945 to 1955 >

Start over —— Ayako Nagata 5

After leaving Tule Lake, Ayako's family returned to Seattle. They got off the bus at Second Avenue, carried their luggage and walked up the hill of Jackson Street to the Japanese language school at the corner of Rainier Avenue and Weller Street, where they met the Kinoshitas. The Kinoshitas, who lived in a relatively large school building, had been introduced to them by a friend of Ayako's father and had contacted Ayako's family, whom they had never met, to live with them.

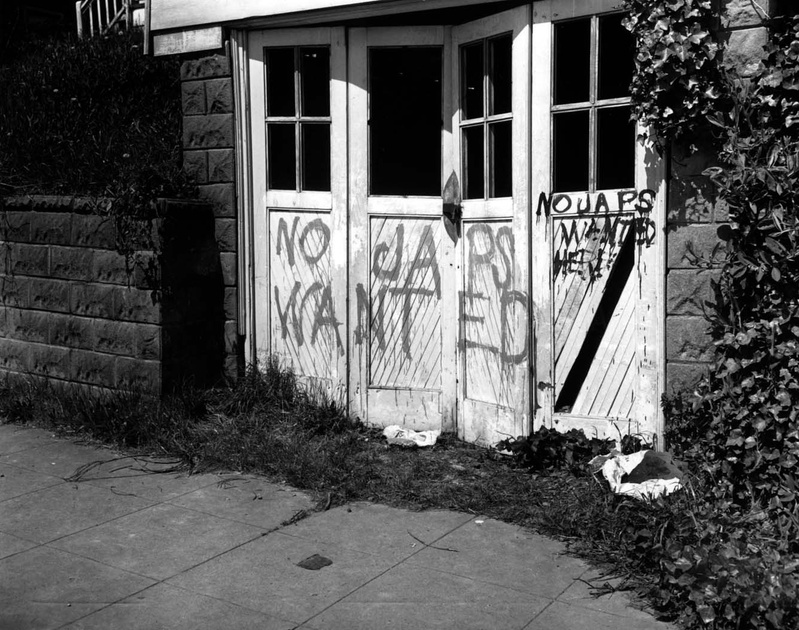

Due to the severe housing shortage after the war and the fact that many landlords still do not want to rent to Japanese Americans, Japanese Americans who left the internment camps had difficulty finding housing and had to use Buddhist temples, churches, trailers , etc. as temporary lodgings. Families who were fortunate enough to return to their homes before the eviction are now looking after multiple families. More than 20 families who returned from Minidoka were also living in the Seattle Japanese Language School classrooms.

My father did whatever job he could get, from cooking at a nursing home to doing outdoor maintenance for the Housing Corporation. However, none of the jobs paid very well, so he was always looking for new work in the classifieds section of the newspaper. One day, he found a job butchering meat and went to an interview, only to be told that he was too timid for the job. My father, who is not one to give up once he has made a decision, begged to work for a week without pay, and was hired full-time a week later. Apparently, the company built a step stool for my short father to make it easier for him to butcher the cows and pigs that came in one after another on the assembly line. It seems that it was hard physical labor, but he worked hard there for about five years...

After that, Ayako's father worked in various jobs, sometimes even working three at a time. When he was working as an elevator operator, a Japanese colleague was fired because he couldn't speak English well. Ayako's father immediately went to the manager and asked him to quit in place of his colleague who had many children. When he got a job at an accounting firm, he was very happy, but he was called in by the director immediately. The director said with an apologetic look on his face, "I like you, but..." He said that all the other employees said they would quit if they hired a Japanese person. Ayako's father replied, "I understand," and resigned on the spot.

My mother returned to the Seattle Glove Factory, where she had worked before the forced eviction, and began sewing canvas and leather work gloves. She was paid by the piecework and had no security. When Boss Manufacturing Co. bought the Seattle Glove Factory about four years before my mother retired, she and her longtime coworkers were finally able to receive union-level pay, health insurance, and retirement benefits. However, her records of her 33 years at the Seattle Glove Factory were not transferred to the new company, and she only worked there for four years, so after she retired, she received only a monthly pension of $10 (1,000 yen). Even so, my mother was always grateful to the Davises, the owners of the Seattle Glove Factory, for giving a job to Issei women who could not speak English and could not find other jobs.

Later, Ayako's mother fell ill and had to undergo surgery. After the operation, while still under anesthesia, she noticed her mother's hands moving slightly. Ayako wondered what this was for a moment, but then she realized it was her mother's fingers sending the fabric toward the needle of the sewing machine as she sewed the gloves, and she was filled with gratitude, saying, "Oh, Mom, thank you so much for all these years."

Rhubarb Farm - Junzo and Rio Itaya 7

What happened to the rhubarb farm, which was the last hope of Billy's grandparents, Junzo and Riyo Itaya?

Let's go back to the time before the eviction, when Junzo was arrested by the FBI on March 13, 1942, and 21-year-old Sammy, who was studying at the University of California, Berkeley, returns home in the middle of his studies to help his mother prepare for eviction alone.

After thinking about what to do with the rhubarb seedlings on the 10 acres he was renting, Sammy signed a contract with himself, the owner of the seedlings, the new tenant who would take care of the seedlings, and the landowner, Paul Wilson. It was April 27th, the day before they were due to eviction. There wasn't much time. The contract stated that the rhubarb seedlings would be carefully grown on the farm, and that once the war was over, they would all be returned to Sammy if Sammy paid Wilson $154 in back land taxes. In the meantime, the new tenant would take care of the rhubarb seedlings, Wilson would sell the harvest, and the profits would be split equally between the three parties.

However, Wilson, who thought he was the owner of the rhubarb farm in Norwalk, California, turned out to be a ridiculous man. It was all a lie. The farm had been seized by the State of California in 1937 for unpaid taxes, and it no longer belonged to Wilson. However, Wilson had evaded the law and collected rent from the Itaya family for many years. Furthermore, within a few months of the Itaya family being moved to the temporary camp, he had dug up the farm with a hoe and destroyed the rhubarb seedlings. The two portable buildings that the Itaya family owned on the farm were either destroyed or taken away, and the last hope of the Itaya family had disappeared without a trace.

Junzo and Rio had no choice but to move in with Billy's family, who had returned to Hollywood, California in 1946 and opened an auto repair shop. For young Billy, the only scar from his time in the camp was a small burn he got when he jumped into a pile of coal embers behind the barracks, and he was not psychologically scarred. But Billy's grandparents had lost everything they had worked so hard to build, and they were too old to start over.

"Welcome Home" on Bainbridge Island

The people who remained on the island read with interest the camp reports that novice reporter Paul Otaki and his colleagues sent to Walt Woodward's newspaper. "...I think it was once a week. Who was getting married, where babies were being born, who had died, etc. Everyone played baseball in the camps, so it was interesting to read about who was on the team and things like that. Everyone on the island read them to find out how everyone who had gone to the camps was doing and how they were doing," says Earl Hansen, who played baseball in the high school. 8

Fortunately, when Sally, Shimako and Nishimori returned to the island, their house, furniture and farm were still there. Thanks to the care of their friends and neighbors, they even sent the things they needed from the things they left behind on the island to the internment camp. However, Sally was very worried.

"Will everyone accept me at high school?" I had barely turned 13, and I was really scared. When school started, I decided to sign my attendance book as Sally, the American way, instead of Shimako. And then... on the first day, Shannon Stafford and Ray Lowry, who had been in my class since kindergarten, came up to me and said, "Welcome back!" and I was like a god . Because I thought no one would accept me.

Notes:

1. Kashima, Tetsuden. (1980). Japanese American Internets Return, 1945 to 1955: Readjustment and Social Amnesia. The Phylon, the Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture, Vol. XLI No. 2.

2. Estelle Ishigo, translated by Nobuaki Furukawa, "Lone Heart Mountain: Days in a Japanese American Internment Camp," Sekifusha, 1992

3. Kashima, Tetsuden. (1980). Japanese American Internationals Return, 1945 to 1955: Readjustment and Social Amnesia. The Phylon, the Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture, Vol. XLI No. 2.

4. Kashima, Tetsuden. (1980). Japanese American Internationals Return, 1945 to 1955: Readjustment and Social Amnesia. The Phylon, the Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture, Vol. XLI No. 2.

5. Peggy Ayako Nagata Tanemura, interview by Yuri Brockett and Jenny Hones, November 21, 2013 at Seattle, Washington.

6. A camper-like vehicle with a kitchenette, toilet, and bed

7. Muller, Eric L. (Ed.). Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War II. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2012.

8. Earl Hanson, interview by David Neiwert, May 27, 2004. Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

9. Sally Shimako Nishimori Kitano, interview by Frank Kitano, February 26, 2006. Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection, Densho.

*Reprinted from the 137th issue (April 2014) of “Children and Books,” a quarterly magazine published by the Children’s Library Association.

© 2014 Yuri Brockett