I work at a Japanese-American community newspaper where, every Halloween, we have the same conversation. Then something happens — like Katy Perry gives a performance, or a fraternity has a theme party — and we have the conversation again. If I had strong feelings in the beginning, they’ve been numbed by time and frequency. I just don’t have the energy to react each time a white person wears a kimono as a costume.

But when the Boston Museum of Fine Arts launched and ultimately canceled an interactive event called “Kimono Wednesdays” — during which visitors could pose with Monet’s “La Japonaise” while wearing a replica kimono — I read the coverage anyway. And though I should know better by now, I read the online comments, too. All that most commenters wanted to do was tell stories about their experiences with Japan and Japanese people. They wanted to say that they’d been to Japan, loved and respected the culture, and wore kimono with the approval, even enthusiasm, of their Japanese friends.

I’ve also been the foreigner in kimono. Although my mom is Japanese, I learned most of my Japanese at a liberal arts college in New England, in a classroom full of white people — white people who, like the Boston Globe commenters, loved Japan, and even found a sense of belonging there that they couldn’t find the US. My dad had been one of them, 30 years before, studying Japanese in Oregon before living in Tokyo for a year. He worked for a Japanese company in Los Angeles, and eventually married my mom.

When I studied abroad in Kyoto, I was one of only three exchange students with Japanese blood. My host mom worked at a kimono shop, where she dressed both tourists and locals, especially for their seijinshiki, the Japanese answer to a sweet 16 party. She gave me a full special-event package, dressing me in a silk furisode with long, dramatic sleeves. Wearing the kimono, though it was constraining and the heavy obi hurt my back, I felt calm and right. When I saw the photos later, though, my heart sank. With my updo and light makeup, I looked whiter than ever, like an interloper in my own motherland.

When I read angry think-pieces on cultural appropriation, my feelings are split. I feel anxiety that, with my white-looking face (green-eyed and freckled), I look like an appropriator all the time: when I wear a yukata to a summer festival at the Buddhist temple down the street, when I buy canned sardines at the market in Little Tokyo, when I include my name in Japanese characters on my Facebook profile. This part of me bristles, wonders who could be worthy or clear-eyed enough to dictate what is and isn’t an example of appropriation in our increasingly mixed-race world.

And then, I admit, I think of the friends whose behavior I haven’t been able to process yet, no matter the amount of time that goes by, because I want an excuse not to see them in a negative light, like the guy who dressed up as a geisha at costume parties, for example — a kind, friendly guy, who spoke excellent Japanese. As soon as I make concessions like that, my mixed-race anxiety kicks in again: am I a banana in my radical Asian-American friends’ eyes, yellow(ish) on the outside, white on the inside?

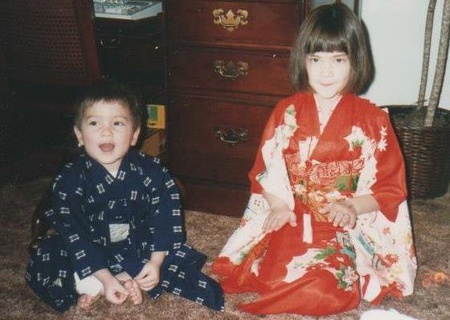

But on top of all that, I think about the times when I’ve felt my words about my identity taken right out of my mouth. The earliest I can remember was that day in sixth grade when I gave a presentation on Japan. My mom had helped me that morning by packing my cousin’s hand-me-down kimono in a plastic bin and making onigiri for the class. I, shy and frizzy-haired, gave my talk about my mom’s country and then sat down, pretty happy to have had the chance to air out this part of myself that usually stayed below the surface, because back then I was still learning how to talk about it.

Then my copresenter stood up, a blond girl I didn’t know, visiting from a different class. She came from a different angle, showing us her manga and J-pop magazines, before proclaiming that, in Japan, men are more feminine than they are here, period. I went home with this feeling that she was probably wrong but that I had no idea how to correct her. I hated my silence, and I hated that she’d had the final, confident word despite not having done much to earn it. I’d been to Japan only twice at that point, the last time being when I was 4 years old. I knew so little about the country, and I had no confidence in the misty, tenuous things I did know. And yet, the things I knew, though limited, were crucial. My mom had always told me that there was just something “in the air” in Japan, and that she wanted me to go there so I could feel it. “In the air” was a big phrase for her. When her mom, my obachan, died, that was also what became of her. She was “in the air.” My mom could feel her. Invisible, improbable, undeniable. That was my Japaneseness to me too.

Here’s what I wish everyone would understand. Japanese people in Japan and Japanese-Americans are not the same. In Japan, where “Kimono Wednesdays” toured before making its way to Boston, the event may have been a mostly unquestioned success. But context is everything. In Japan, ethnically Japanese people have little reason to feel anxious about their identity, or to feel that one person in costume in a public place can take it away from them. Their right to Japaneseness is reinforced everywhere they look, just as Americanness is for white people in the US.

I can’t speak for all Japanese-Americans, but I can speak for myself, one twentysomething mixed-race woman with a Japanese mom and a white American dad. I spend so much energy shouting about my identity from the rooftops, trying to make sense of it, trying not to care when any group questions my right to be a part of it. And when I tell you that I’m offended, as protesters told the Museum of Fine Arts, that’s not a superficial, knee-jerk reaction, but one that comes from that deep, raw place within me where all those intangibles about culture live. No matter how often I speak from that place, it continues to hurt and feel dangerous. Will this person listen, I think, or take me seriously, or completely reevaluate our relationship when they hear what I have to say? For that effort, I don’t expect to get my way. But I do hope to be heard.

Here’s one comment that stuck with me most, from Martha1: “I made deep and lasting friendships with a college student who came here to study for a year and who was from Tokyo and then with a grad student from Osaka. We attended the BSO and MFA and other venues together and spent several years in one another’s happy company in Boston. . . . I cannot imagine them feeling anything other than happy that I loved the kimono. I cannot imagine!”

As earnest and well-meaning as Martha1 sounds, it’s lack of imagination, ultimately, that is the problem here, the lack of willingness to consider someone else’s position. To consider that the OK of one Japanese friend who likes your kimono doesn’t mean wholesale approval from all Japanese people, let alone Asian-Americans. Or to consider that even if an act — a harmless one like putting on a costume in front of a painting — isn’t wrong, it might not be right either. Most of all, what I wish we’d do in the face of race-related protest is listen, consider other possibilities, then have a real conversation.

I imagine my white grandma, who reads my articles in the Japanese-American newspaper and recently sent me an embroidered greeting card featuring a crane next to a stone pagoda, waiting in line at the Museum of Fine Arts to try on a kimono and stand in front of a Monet. I imagine her — in her sweatshirt-over-turtleneck combo, her gray hair dyed red and newly set — being called a racist, a colonizer, and I feel embarrassed, protective, sad. I hope she would read the protesters’ signs and think, really think. (I hope the protestors would treat her gently.) I hope she wouldn’t say, “My granddaughter is Japanese and she wouldn’t mind.”

* This article originally appeared in The Boston Globe on July 10, 2015.

© 2015 Mia Nakaji Monnier