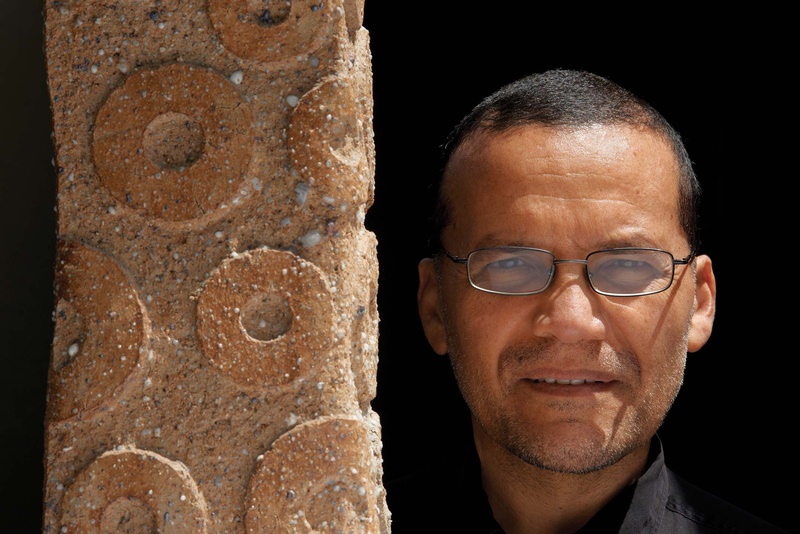

All art is made of life, but not all life is made of art. The Peruvian Carlos Runcie Tanaka 1 (Lima, 1958) has managed to assemble in a single piece the real and the imagined, the human and the divine, the body and the spirit, in a work that began in the eighties, when he decided to renounce the Philosophy degree to devote himself, along with clay and fire, to ceramics.

And it hasn't been easy. His first teachers were those from Taller El Pingüino in the Miraflores district, directed by Mariano Llosa, Pedro Mongrut and Jody Krafsur Nolan. He was just over 20 years old and wanted to be a composer and singer, but he let his hands do the talking in those pieces fired at high temperatures that he then sold on the street, on the corner of Larco and Benavides avenues, when the municipal police wouldn't let him. prevented

Then came the silence and the voice. He traveled to Japan to be the deshi , the apprentice, of the ceramist Tsukimura Masahiko, in the Ogaya mountains, where he had a totally oriental and reflective apprenticeship. “Cutting down trees, chopping firewood, kneading clay… We didn't read books, he had studied philosophy and I think that's why we had a lot of empathy,” says Carlos, who later became Shimaoka Tatsuzo's guest apprentice briefly before traveling to Italy.

He had won a scholarship from the OAS and the Italian government to follow a course at the State Institute of Ceramic and Porcelain Art of Sesto Fiorentino, in Florence, where he became more eloquent (he stayed six years), as now when, Sitting in his house museum, he lets the thick voice circulate, full of memory, of the 56-year-old man who, at half his age today, decided to return to Peru and open a workshop that operates in this same silent place.

A painting by the artist Jorge Eduardo Eielson welcomes you before entering the room, where the paintings of other friends coexist with their utilitarian ceramics (candy bowls- boxes of dreams , vessels, plates-trays), their clouds (glass spheres the size of a world map) and pieces that will be assembled into other works by an artist who exalted ceramics and who in the following years would explore installation and other forms.

burning facets

In his first stage, Runcie Tanaka's ceramics were inspired by pre-Hispanic cultures, those that resonated with his soul ("the Sechín, the Chavín, were warrior peoples and priestly castes") and that he met thanks to a professor at Markham School who I took them to museums. “While my friends played soccer, I collected huacos and ceramics,” he says before telling me his next facet.

It was 1987, and the artist took his ceramics to the Punta Hermosa desert, 40 kilometers south of Lima, to plant them in the sand. There, photographer Javier Silva photographed them under the last beam of afternoon sun. Desierto al Sur de Lima was the name he gave to this intervention in the landscape that would later give rise to one of his first individual works that was mounted at the Trilce Gallery, “but there was no life there. Where is life?” Carlos asks himself, leaving his artisan hands free.

Intervention, 1987

Km 40 Panamericana Sur

Trilce Gallery, Lima, Peru

Photography: Javier Silva

Some time later, in 1994, while riding waves in Pasamayo, he almost drowned. He found himself thrown back by the sea, surrounded by crabs that were coming towards him, and he thought about his immigrant grandparents (the British and the Japanese) who also ended up stranded on this coast with which he identifies. He then remembered that that same year he had seen in Cerro Azul, 130 kilometers to the south, hundreds of small crabs dissected by the sun at the foot of the obelisk that commemorated Japanese immigration to Peru. In that slow - walking crustacean he found the symbol of time, of movement, of the passage of life, and he took it to his ceramics.

It was then that he made the connection again with Japan, a country that he had visited between 1979 and 1980, looking for an excuse to reconnect with his roots, and where he would receive the foundations that allowed him to make this profession a way of life. His house, museum and workshop is a tribute to that oriental temple. Music is not used here, although Carlos has a piano in his living room, and certain rules of order and discipline are followed. “To those who want to work and study here, the first thing I do is suggest reading some basic books for a ceramist, which many cannot bear…”.

Separated from the room by a garden full of round cacti ( echinocactus grusonii , better known as mother-in-law's seat), three assistants lead a monastery life although they dialogue with the teacher, who asks for opinions and contributions. “You are going to be better than me,” he repeats while showing how each piece has a unique finish, a different grain, a varied combination of colors and shapes. “Without them I could not have made so many ceramic objects… imagine, I would be confined to a wheelchair.”

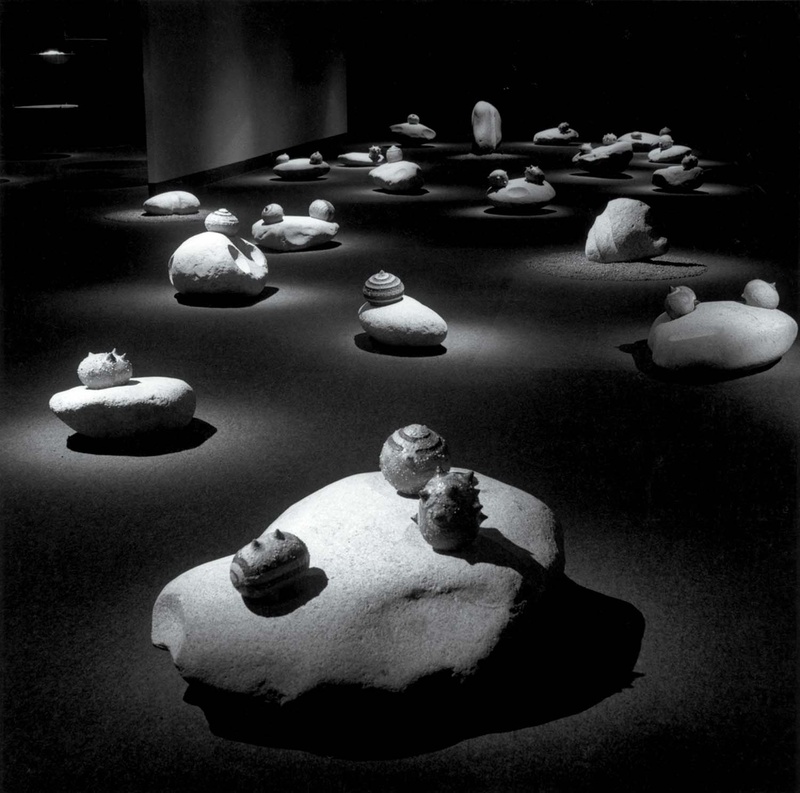

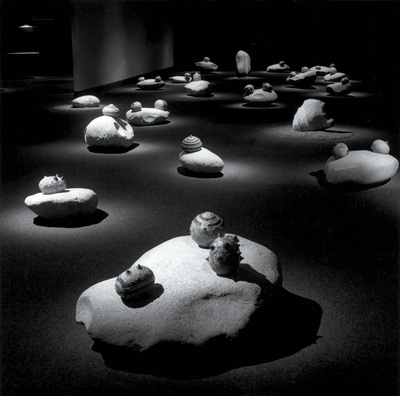

The artist's cry

Tonalli Gallery, Ollín Yoliztli Cultural Complex, Mexico City, Mexico

Photography: Michel Zabé

There is in Carlos Runcie Tanaka's speech a hoarseness of someone who does not raise his voice, but whose art has had to shout to be heard among sculptors and painters. First it was in Mexico, where thanks to a scholarship he was able to work for several months in the workshop of ceramist sculptor Hugo Velásquez in Cuernavaca to mount the installation Ceramics/Paisaje de Tezontle , in 1991, in the Tonalli gallery in Mexico City. “A large space of approximately 1,200 square meters that I filled with 12 tons of red volcanic stone and my pieces resting on stones.”

Three years later, in Lima and with a Pedro Infante mustache, a thin ribbon over his upper lip, he would fill a 1,500 square meter room of the Museum of the Nation (the individual Displacements ): obelisks, vessels with turquoise interiors resembling water , pierced stones, and other pieces that constituted “an act of defiance to the oscillations of art,” as Silvio de Ferrari Lercari wrote for the newspaper Expreso.

“I came with the experience of presenting works in several biennials, I had already grown up…” says the craftsman and installer who believes that today artists are like athletes prepared for great demands. Constant exhibitions, international art fairs and scholarships to compete with talents from all over the world. “In the eighties and nineties, few Peruvians had the opportunity to exhibit outside the country and among them, I remember Moico Yaker and I were. At the end of the nineties and from the year 2000 another generation began.”

The last shout of those decades came with the kidnapping at the Residence of the Japanese Ambassador, in 1997, from which Runcie Tanaka left after 10 days, only to contemplate the ceramic pieces (among them, the hands that he had begun to turn) that he had hostages in his workshop, just as he was. This is how The Wait was born and then Stopped Time and a phrase that he wrote when he returned home and that was going to become his personal prayer: “It's not what you think, it's not what you see, not what you feel, not what you don't see.” , it's not what you say, it's not what you play, it's not what you hear...".

The broken pieces

“The words come back to me,” Runcie Tanaka says as I drink water from a three-legged glass. He writes in the spheres and on the clay the texts of poets and friends (Eielson and Blanca Varela) and the prayer that in 2001 becomes The same prayer , an installation of dark spheres, which would be followed by a period in which he participated in various group exhibitions and a couple more individual exhibitions in which he explored with photography, ashlar, origami, sounds, feathers, videos.

The parenthesis closes with Sumballein . Exhibited at the San Marcos Museum of Art in 2006, Carlos, still with a mustache but with a shaved head, presented more than 2,000 broken pieces that he had reintegrated using the same ceramics and successive firings in the gas oven, leaving seams on the surface in what curator Gustavo Buntinx 3 defined as “a work linked to the breaks and reconstructions of our country.”

The broken anthology started from an idea that he now summarizes as “not letting the object die.” Those same pieces surround us in the house museum. He didn't want to get rid of them. Vessels with war wounds, reintegrated trays that look like prehistoric turtles, chocolate boxes with scars like the one on his left arm, from which three arteries were removed when his heart also broke.

With Sumballein, he seemed to have reached the top, but he discovered that it was not full of roses. “Ceramics are a kind of poor relative of sculpture,” he says, without the anger that in those years led him to fight to value the work of those, like him, who dedicate themselves to an art that has been practiced since its origins. From Peru. “You crash into reality,” says Carlos without a mustache, still accelerated but who has learned to take things calmly.

The reinstated artist

He almost drowned, escaped from a kidnapping and in 2008 underwent two heart operations. A year before, 10 days after presenting the individual Solo Nubes , composed of glass spheres that, unlike ceramic, allowed him to pass through the volume through transparency, his father died. “My dad loved these spheres because of the light, the exhibition was dedicated to him. I almost canceled the project but in the end I decided to pay tribute to him and put up a video with photographs of clouds that his father, the photographer Walter O. Runcie, took.”

And singing. “ Both sides now ”, by Joni Mitchell, whose lyrics say “now I see the clouds from both sides.” It was a very hard mourning, which was followed by her last single, Into White , in 2010, where there was almost no ceramics; Everything was dominated by the transparency and brilliance of the glass crabs. Art is made of life, that is why Carlos continues to create, showing his work abroad, participating in exhibition halls such as the one offered to him by the Enlace 4 gallery on a permanent basis.

“We are working on several interesting projects that are no longer large exhibitions, but for which I am very fond.” One of the last was called Vínculos , and was exhibited at the first edition of the Perú Arte Contemporáneo (PArC) fair in 2013. Colored ribbons surrounded a tree and rose to form a festive wreath that linked the Museum of Contemporary Art. A “very rare, radiant, playful” Carlos Runcie, with a graying mustache and a fresh smile.

Installation, 2013

PArC 2013 / Museum of Contemporary Art - MAC, Lima, Peru

Photography: Juan Pablo Murrugarra

As I piece together the last fragments of the conversation with the craftsman, the artist, the installer, the survivor, the art warrior; I remember his last battle, the missing piece of a work that will continue to be fired in the high-temperature ovens of his house museum: the idea of supporting colleagues and achieving the creation of a school dedicated to learning ceramics in Peru , this is a mission and a debt with the country that wants to promote; a way to give back to art what it gave to his life.

Grades:

1. His biography ( Spanish / English )

2. Interview with the Nikkei in Descubura

3. SUMBALLEIN: BROKEN ANTHOLOGY BY CARLOS RUNCIE TANAKA (1978 – 1996)

4. Catalog

© 2015 Javier Garcia Wong-Kit