Takashi and Shizuko (nee: Mori) Kato and their two children, Roy Shigehisa and Ikuko, moved from Inglewood to West Los Angeles just prior to evacuation to Manzanar. They left everything behind with their lost nursery business; the property had been taken over by the U.S. Army apparently because of its proximity to LAX and used to encamp soldiers. That was their first experience with camouflage nets and guns surrounding them—and earned them a picture of their invasion of privacy in Life magazine.

In 1945, before the family left Manzanar, Takashi left camp to bring a truck from Los Angeles. (Note: Initially, Iku thought Takashi had gone to purchase it, but during a clean up after her mother’s house was sold, she came upon photos of the truck and a receipt for repair work. The receipt was dated prior to the evacuation. Iku thinks the truck must have been left with a hakujin1 couple, the Thorntons. Mr. Thornton had visited at Manzanar, at least once that Iku recalls.)

There was much excitement when he returned with the GMC truck. People milled about the truck as Iku, then 5, ordered the other children not to touch the truck. Roy had collected his precious supply of round, green “balls” (which when emptied of their white seeds you could stick in your mouth and blow up), only to have it confiscated by an adult who gave it to his child.

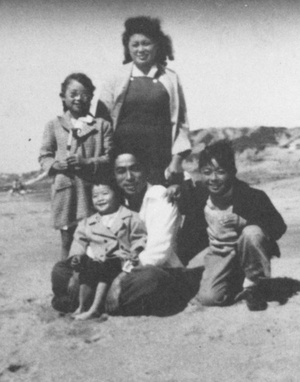

The family of five (sister Aiko was born in camp) crammed into the cab of the truck and made the long drive back to Los Angeles.

With nowhere to go, the Kato family stayed with another family in one room at the Truman Board Housing Project in Long Beach. Takashi looked every day for work and for another place to stay, finding a rental in Torrance after 3 months.

The house was on Meyler Street near Harbor General Hospital on a dirt road with few houses around. The property seemed large (at least in Iku’s eyes as a child). The house had basically one room. Divided in half, the family slept on two beds in the larger half with a sheet or bedspread draped across the opening to separate it from the kitchen.

There was no bathroom. An outhouse was in the middle of the field behind the house, and to bathe, Shizuko boiled water and filled a round galvanized tub—the size people now use to fill with ice and put in cans of soda or watermelon. They each took turns bathing in the same water. Takashi could barely sit in the tub with his knees raised clear to his chin.

An Italian American family, the Busches, lived across the street. Roy and Ronnie went to Meyler Street Elementary School together for a short time. Later, the children went to Torrance Elementary School. Iku’s English was still not fluent and she had difficulty reading. Her first and second grade teachers, Miss Cole and Mrs. Saunders, gave her extra help during the recesses.

Iku doesn’t recall any abuse, but Shizuko told her many years later that both she and Roy had been beat up at school. Iku does recall Aiko being taunted by a boy when she was in the fifth grade at Crenshaw Elementary School (long since closed) on Crenshaw Blvd. between 182nd and 190th Streets.

Surprisingly, the worst treatment the Kato family encountered in the early years of resettlement was at the hands of another Nikkei. A Kibei Nisei was the landlord of the house on Meyler. When he was offered money for the house—or, it may have been the property itself—he began harassing the family to force them to move. He would contaminate the gas tank and destroy other property. Shizuko nagged Takashi daily to find another place, but times were hard and Takashi was still supporting the family by gardening.

Finally, in 1947, Takashi found a five-acre piece for rent on Crenshaw Blvd. in North Torrance. A kindly white widow, Mrs. Wing, was the landlady. She and her family treated the Katos well, bringing home-baked cookies and other goodies. To this day, the sight of the white snowball cookies at Christmas evoke memories of the first cookie brought by Mrs. Wing.

The house on Crenshaw was like a mansion to the children. It had a kitchen, a living room, 2 bedrooms (actually 1 bedroom and a small area where Takashi slept)—and—a bathroom. What luxury!

Mrs. Wing’s father had built the house. The kitchen was added on later—literally. It sat on the ground and was slightly separated from the main house. Slugs would come in during the night and settle on the wood surrounding the sink. Yech!

Besides the house, the property had a huge barn and a windmill. Art students from El Camino Junior College would sit across the street and sketch the buildings.

The closest neighbor was San Lorenzo Nursery on the east side of Crenshaw to the south. From the Kato property clear to 190th Street was only a lima bean field. You could see General Petroleum (now Mobil Oil) from the ground up. A Mexican American family, the Yniguezes, farmed corn on what must have been 10 acres, north of 182nd Street. Across from them was Verburg Dairy, a Dutch family. Iku would walk there every day to buy milk in glass bottles. Tract homes started being built around 1950, 1951. The days of gleaning fields for lima bean were over.

The Katos could not afford a refrigerator for a year or two and used a wooden apple box set on one end as an icebox outside the kitchen window. A cloth was draped in front. Food was placed on the top “shelf,” and a block of ice was on the bottom. They later bought their first refrigerator—a Philco. A television was not to be afforded until 1953.

The children’s entertainment was radio. The programs came alive in their imaginations: The Green Hornet, The Fat Man, The Thin Man, Batman, The Cisco Kid, I Love a Mystery, Superman, Amos & Andy, etc., etc. Whenever Takashi had a kenjinkai meeting, Shizuko would ask the children, “Do you want to eat in front of the radio?” To which they would happily say, “Yes!” and scamper to clean off the small table in the bedroom. There, they would eat the “Papa’s at a meeting” special treat, homemade tortillas and beans, and listen to their favorite programs with rapt attention.

Takashi believed in community involvement and was a founder of the kenjinkai of his prefectural village in Kagoshima, Kaseda-kai. Kaseda is probably the only village to have its own association. They were also members of the prefectural Kagoshima Kenjinkai. Kaseda-kai had a “tanomoshi” club, annual picnics, and annual dinners. Because of lack of interest from the “younger” generation, Kaseda-kai has dropped its activities to its lone annual “shinnen-kai” New Year luncheon—with even that doomed to extinction as of 1999. Takeshi served as its president and also held office with the prefectural group. Among the big families of Kaseda-kai were the Nishis, the Yamashitas, and the Seinos.

Takashi brought home slips of plants from his gardening route, and Shizuko planted them. Slowly, by being very frugal and working long hours, Takashi and Shizuko were able to start their own nursery business again.

Like most family-owned businesses, the Kato family never had a regular day off. New Year’s Day was the only planned full day off. Roy and Iku had to work every day after school, weekends and summers from elementary school until they graduated from high school. Iku remembers only one trip—to San Diego for a day. Otherwise, family “outings” were Kaseda-kai related, funerals, and weddings (eaten at San Kwo Low!), and occasionally to the “rocky” beaches to gather “mina” (sea snails).

They planted acres of pansies and sold mostly wholesale and some retail. After their first year, they decided to gift all the teachers at Perry Elementary School with baskets of pansies. They wanted to show their appreciation to the teachers; however, this gift came to an abrupt end in its third year. Iku remembers standing in the foyer early one morning while her father brought out the pansies. One female teacher came stalking up, red in the face, and yelled at her father, “I didn’t get my pansies!” and took it from him without so much as a thank you and left. Takashi didn’t say anything. The next year there were no pansies in the foyer. The gift of pansies was a financial sacrifice for the Katos who could afford only one outfit and one pair of shoes per child per year. It was normal and natural for the children to grow into the oversized clothing and shoes. The shoes wore out before their feet grew into them. Iku thought all children put pieces of cardboard in their shoes when the soles wore thin and showed gaping holes.

Iku remembers, at about age 8, standing on the roadside, selling pansies. She didn’t know how to handle change, and, one day, an elderly white gentleman taught her how. He told her she needed to know how to count change back and patiently had her do it over and over.

The Katos soon added chrysanthemums to their stock. Every morning during the summer, Roy and Iku would wake up while it was still dark and help their parents fill the cans and load them onto the turn-table while Takashi and Shizuko would make holes and put in the mum cuttings. They would finish by the time the hot summer sun blazed down.

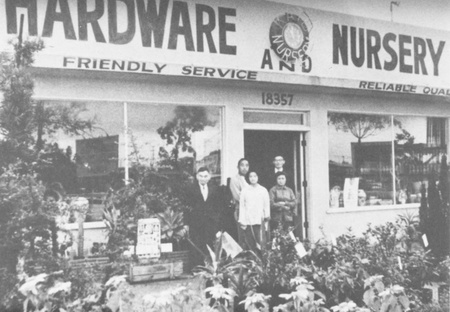

Around 1954, Kato nursery had a grand opening of their new store. By the end of the fifties, the state made plans to extend the San Diego Freeway with an off-ramp at Crenshaw Blvd. They claimed eminent domain and the Katos were forced to relocate their business after having been established there for thirteen years. Takashi and Shizuko had filled in probably 2 or 3 or more cubic acres of dirt; the property dropped down about 3 or 4 feet from the road. The state assessed the value at the original unfilled condition when the Katos had purchased the land from Mrs. Wing. The new store, a new home, and the established business were not taken into consideration. Takashi was so angry, he said he didn’t want to keep anything, including the new house. He later regretted it and wanted to keep the house, but the state said it was too late and auctioned it off. They said he could bid for it and pay the state, but he couldn’t afford it. He looked so defeated.

They had just enough to relocate to Artesia Blvd. near Western Ave. in Gardena (the property now just east of Marukai). For two years, they lived in an apartment across the street and ran across Artesia Blvd. several times a day for two years.

In the late sixties, there was talk of possibly connecting the San Diego and Harbor Freeways, using Artesia Blvd. When they were told they might have to move again, Takashi exploded. He emotionally complained that this democratic U.S. government was so unjust. First, they threw him into a concentration camp; then, they kicked him out of his hard-earned business on Crenshaw; and now, they were going to shaft him again. How could he start another business in his seventies? Each move had been a costly setback in years and money lost.

It was the first time Iku remembered hearing her father say anything bitter about the war-time incarceration. And the last.

Note:

1. Literally “white person,” the term most Japanese Americans used to refer to European Americans.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices, Resettlement Years 1945-1955 in 1998. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 1998 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California