Satsuki Ina (70), professor emeritus at California State University, Sacramento, was born in May 1944 in the Tule Lake internment camp in California. She is a counseling professional who has worked to provide mental care to Japanese Americans who experienced life in the internment camps.

In my previous essay , I mentioned that Ina was involved as a producer in two films on the theme of concentration camps, and introduced the content of one of them, "From Cocoon of Silk," which centers on the experiences of Ina's parents.

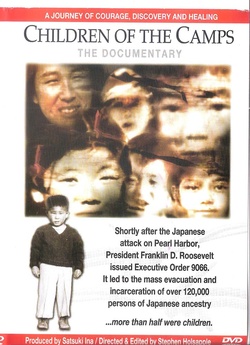

This time we will look at another film, "Children of the Camps" (1999).

As I watched "Camp Children" many times in preparation for writing this article, I came to feel that this film must be preserved for future generations as a documentary about Japanese Americans.

"From the Silk Cocoon" is a dramatization that depicts the emotional reactions of Japanese Americans who experienced wartime internment, but "Children of the Camp" is 100% documentary, with no actors playing any of the characters. Moreover, there is no acting or script in the footage, just the emotional reactions of the participants recorded as they were.

And thankfully for Japanese audiences, the film "Kids at Camp" is available in Japanese, and the translation is very easy to understand.

"Encounter Group" is the name of group counseling that became popular in the United States in the 1960s. In the early 1970s, I experienced an experimental "Encounter Group" that was very rare in Japan at the time, and was led by Yuzuru Katagiri, a professor at Kyoto Seika University who introduced American culture.

In fact, the film "Kids at Camp" is a record of an "encounter group" in which counselor Ina acts as a facilitator (a term used in encounter groups, referring to a person who acts like a moderator and creates an environment where participants can easily speak up) to capture the emotional movements of six people, three Japanese men and three women who spent their childhood in internment camps.

In the "Encounter Group" I participated in in Japan, I was surprised and moved by the rapid changes in my own heart and the hearts of the other participants. It seemed impossible to reproduce that experience in words or on paper, and I never imagined I would record it on film and release it as a movie.

The records of group counseling sessions, which contain many very personal aspects and are difficult to turn into a film, still move people who watch them today. This is because as many as 120,000 people experienced wartime internment camps, and even now, 70 years after the end of the war, there are still many people who bear emotional scars. In other words, there is a common understanding between the viewers and the characters in the film.

The narrator of the film "Kids at Camp" explains only that "This footage is a record of a workshop held in the early 1990s," without revealing the location or date of filming. What appears to be the Pacific coast of northern California is shown. As one watches the footage, it becomes clear that the workshop took place over a three-day weekend. Furthermore, several interviews with participants filmed after the workshop are inserted into the scenes of the workshop in progress, effectively conveying to the viewer the changes in the participants' hearts.

The film does not provide any details about when or where it was filmed, and the privacy of the participants is kept to a minimum.

Even Ina, the producer of this film and the facilitator of the workshop, is only mentioned in the film as having been born in the Tule Lake Internment Camp. The fact that the participants' privacy is not made public and the focus is solely on the movements of people's hearts is in fact the very method of the "Encounter Group."

In the "Encounter Group," participants can introduce themselves by their name, which does not have to be their real name. They can also create a nickname that they would like to be called on the spot, rather than the nickname they normally use.

Without giving away any spoilers, but to get you interested in the characters in the film, here are the six workshop participants, all of whose names are their real names:

Toru Saito: At the age of four, he was sent to the Topaz Internment Camp in Utah. His mother could only speak Japanese. He felt his mother's suffering in the camp as his own. After the war, when he left the camp and went to school, he was always bullied, told "You're a dirty Jap," but his teachers didn't help him at all. In the film, he repeatedly makes the most aggressive remarks to others, but in the second half of the film, Toru himself reveals the reason why.

Howard Ikemoto: When I was two years old, I was put in the Tule Lake Internment Camp in California. I have no doubts about whether I am American or Japanese, and I have always been certain that I am American. That is why I feel that I was pushed away from my homeland, America, by the internment.

Ruth Yoshiko Okimoto (PhD) was sent to the Poston Internment Camp in Arizona when she was four years old. She often dreams of a rifle with a sharp sword attached. She has no memory of ever seeing such a rifle, so she is always frightened as to why she has such dreams. After the war, she lived in San Diego. At school, she was always bullied for being Japanese, but when she was in the fourth grade of elementary school, a black girl used her body as a shield to protect her.

Richard Tatsuo Nagaoka was born in the Lower Internment Camp in Arkansas. After the war, he lived in Lodi, California, where his family was the only Japanese people in the town. He always wished he didn't look Japanese. His father cultivated a 40-acre vineyard by himself. He wanted him to take over the business, but his expectations were painful for him.

Bessie Masuda: At the age of 11, she was sent to the Lower Concentration Camp in Arkansas. She cannot forget the fear she felt when her father was taken away by the FBI in the camp. She has always had the feeling that she was a child who had been abandoned by someone, and that there was something missing in her.

Marion Kanemoto was in the Minedoka internment camp in Idaho, but her family volunteered to return to Japan, and when she was 14 years old, they were sent to Japan on a prisoner exchange ship. The Kanemoto family was used as an exchange for Americans who had been captured in Japan. For Marion, who grew up in the United States, Japan was a completely foreign country, and she never felt accepted by the Japanese people.

As Ina explains at the beginning of the film, the parent generation (Issei and Nisei) never told their children (Nisei and Sansei) about the wartime internment. That is why, like Okimoto, they have experiences where they dream about a rifle with a sword attached, but don't know why. In reality, they saw the same scene in the internment camp, but it was erased from their memory.

"Camp Kids" is not a film that blames the parents for not telling them the truth. On the contrary, it is a film that uses group counseling to awaken erased memories and understand the experiences of the "children," thereby empathizing with the "parents'" pain and trying to ease their suffering. Many of the "parents" have already passed away. However, the subtitles at the end of the film read, "This film is dedicated to our fathers and mothers."

© 2015 Shigeharu Higashi