After the war, the area was scattered and reduced in size.

The number of pages that "Centennial History" devotes to introducing each state does not seem to be related to the number of Japanese living in that state or the number of Japanese immigrants at the time. The Japanese people of Utah, which was introduced in the previous chapter, are introduced over 44 pages, but the neighboring state of Nevada (Chapter 10) is only five pages long.

In 1910, the number of Japanese in Utah was 2,110, and in Nevada, there were 864. Given this ratio, there is little information on Japanese people in Nevada. The reason for this seems to be that while a large Japanese community continued to exist in Utah even after the war, the situation was different in Nevada.

"With the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, people in the copper mining areas were forced to leave, and after the war only a few people working in commerce returned. The numbers in other areas also decreased, and the Japanese people in Nevada are scattered all over the state, and are currently in a worse position than before the war."

In Utah, there were 4,452 Japanese Americans in 1950, after the war, while in Nevada there were just 382.

As a miner and railroad worker

Nevada, which is now home to entertainment hubs such as casinos in Las Vegas and Reno, borders California to the west and south and is mostly made up of desert and mountains, and before the war there was nothing to see there other than mining.

Japanese people first came to this area in the early 1900s, working as railroad laborers and domestic laborers. The San Francisco-based Japan Industrial Association, which provided labor and employment, established a branch in Reno and sent railroad laborers there. Around 1940, there were about 30 to 40 Japanese people living in the Reno area, and there was one Japanese-owned nursery, one hotel, one Western-style restaurant, and one laundry in the city.

Around 1905, over 200 people from the Japan Industrial Association were sent to eastern Nevada to work on the construction of a new railroad in conjunction with the development of the mines. After the development of the Nevada copper mines, Asians were initially unable to work there due to resistance from the labor union, but in 1912, Toyoda Seitaro, a native of Hiroshima Prefecture, sent workers there.

In 1942, after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, anti-Japanese sentiment in this area suddenly increased, and Issei were arrested and put in a detention center in Salt Lake City, Utah, and some even committed suicide.

Many Japanese people fell ill in the Ely region, which "had the feeling of being a den of rough men." By the time war broke out between Japan and the United States, there were gravestones for approximately 50 Japanese people.

Becoming a pioneer in the desert of Las Vegas

Japanese people first came to the Las Vegas area in 1904 and 1905, when they came to build the railroad there. At one time there were several hundred people living there, but by 1925 there were only a few Japanese working there.

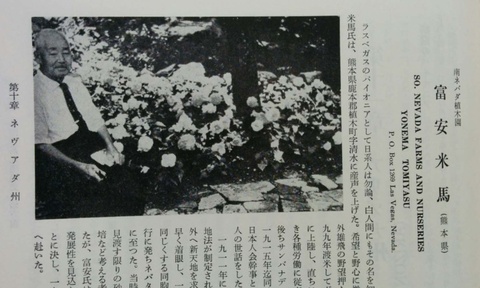

It was in 1913 that Tomiyasu Beima, who would later become a local pioneer and a well-known figure among Japanese people, arrived in this area.

The "Centennial History" provides a detailed account of Tomiyasu's life as the manager of the Southern Nevada Botanical Garden, from his childhood to around 1960.

"Mr. Tomiyasu was born in Shimizu, Ueki-cho, Kamoto-gun, Kumamoto Prefecture. Burning with hope and ambition, he had an uncontrollable desire to go abroad, and in 1899 he traveled to the United States, landing in Victoria. He immediately went to Northern California, where he worked in various labor jobs, and later came to San Bernardino, where he stayed until 1915, looking after the Japanese residents there as a Japanese secretary.

When the Exclusionary Land Law was enacted in California in 1911, Tomiyasu quickly decided to seek new territory outside the state, and in 1913 he set off on a study trip with several like-minded compatriots, arriving in Las Vegas, Nevada. At the time, Las Vegas was a desert as far as the eye could see, and no one even thought about growing plants, but Tomiyasu saw the area's future development potential and decided to emigrate, arriving at his current location in 1915.

Located in the middle of the desert and with no irrigation facilities, the development of Las Vegas progressed slowly and was fraught with hardship, but the tireless efforts of the entire family paid off, and the plain was finally successfully developed, a process that continues to this day.

The desert city of Las Vegas was thought to have no water sources, but Tomiyasu finally found a water source on the outskirts of Las Vegas and acquired 160 acres of land there. Before the war he cultivated vegetables, and during the war he raised chickens and ran the Southern Nevada Nursery.

The land that Tomiyasu purchased had a large amount of water gushing out, and the area was developed into residential areas. As a pioneer in the area, a road was named "Tomiyasu Lane." Even after settling in Las Vegas, he continued to serve his fellow Korean residents and make a great contribution.

(Note: I have used the quotations as faithfully as possible to the original text, but have made some edits. In the previous announcement, I said that this time I would be introducing "Japanese Americans in Utah, Part 2," but due to circumstances, I have changed it to "Japanese Americans in Nevada." Thank you for your understanding.)

*Next time we will introduce "Japanese Americans in Arizona and Colorado."

© 2015 Ryusuke Kawai