Read Chapter 1 (1) >>

2. Premonitions <1939 – Until the attack on Pearl Harbor>

Henry Miyatake is a lively middle school boy who lives in Seattle's Japantown. His family consists of five people: his parents, his older sister, and his older brother. When his father first came to the United States, he grew lettuce in Huntington Beach, California, together with other Japanese immigrants. However, the lettuce would often get black, sloppy bits on it, and Henry's father thought it would be inedible for the two of them, so he sold the lease on the farm to his partner and moved to Washington State. After working on railroad construction, he now runs a grocery store in Seattle's Japantown. Thanks to his parents' subtle consideration and living in Japantown, he spent his childhood without feeling much discrimination.

After World War I, the number of immigrants from Europe increased dramatically, and to help them quickly become accustomed to the American lifestyle, classes to learn English and American culture were held in chambers of commerce, churches, workplaces, libraries, and other places across the United States. Bailey Gazert Elementary School in Henry, where many immigrant children attended, also ran this Americanization program. Henry spoke about this in an interview for Densho: Japanese American Legacy Project 1 :

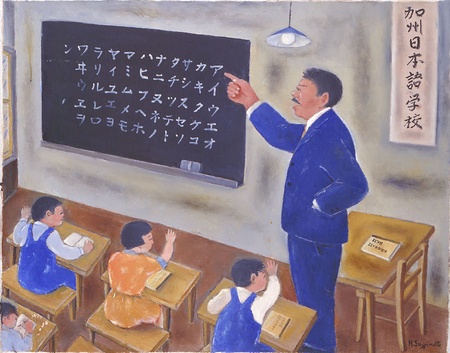

I went to Japanese school. Every day, after the local elementary and junior high school classes were over, I think it was from 4pm to maybe 5:30pm. I was between 6 and 12 years old, so I went there for 6 years. I wish I could have improved my Japanese a little more. I was messing around at Japanese school. Our teacher was Mr. Hashiguchi, and he was a really good teacher. He tried really hard. We knew we weren't bad at studying.

We just didn't do what the teachers told us to do and acted like we couldn't study. So when I brought home essays and tests from my Japanese school and showed them to my mother, she would say, "Oh," and then mutter something to herself. But I had done well at the local school, Bailey Gazert Primary School, so I guess she had no idea why I wasn't studying harder at my Japanese school.

"Why didn't you do it properly?" he asked.

We were so much propagandized by the Bailey Gazzart. I can say this now, but at the time I didn't even realize what was going on inside me. I didn't realize that deep inside of me, I was prejudiced against anything Japanese or Japanese behavior, as if I was a pure American. I was too naive to understand such things .

Madeleine Sugimoto, gift of Naomi Tagawa, Japanese American National Museum [92.97.116]

Many Japanese children went to Japanese schools to study Japanese language, but Yoshiko and her sister Keiko did not. Perhaps their parents had a view on education that they did not want to be forced to do so. When Yoshiko was in middle or high school, she wrote about her strong feelings of rejection of Japanese culture.

Despite the full intermingling of Japanese qualities and values in our lives, my sister and I never thought of ourselves as anything other than American as children. In school we learned to salute the American flag and to be good citizens. All our teachers were white, as were many of our friends. Everything we read was in English, which, of course, was our native language. ...

Society made us feel ashamed of the things we should have been proud of. Instead of directing our anger at the society that had ostracized and hurt us, the atmosphere of the time made many Nisei people try to cast aside their own Japaneseness and the Japanese attitudes of their parents, and our self-esteem was so low. We often felt ashamed of the Issei because of their shabby clothes, their worn-out trucks and cars, their tanned skin from years of working in the sun-dried fields, their inability to speak English, their habits, and the foods they preferred.

I was perplexed when my mother behaved in ways that seemed to me un-American, and I cringed when, together with my mother, we met a Japanese acquaintance on the street and he initiated a lengthy bow while speaking the whole time in Japanese.

"Come on, let's go, Mom," I said, tugging at her sleeve and interrupting her .

In October 1941, a freshman sat next to Henry at Washington Middle School. The war had already started in Europe. One day, Henry was assigned to write his autobiography and was to present it to the class. The freshman's family was Polish and Jewish, and he frankly told Henry about the persecution that had been caused by the German army, his own family, and how he had escaped to America through England. He made a strong impression on Henry.

In early 1941, when relations between Japan and the United States began to deteriorate, President Roosevelt asked journalist John Franklin Carter to investigate the loyalty of Japanese Americans living on the West Coast to the United States. One of several investigators Carter hired was Detroit businessman Curtis B. Munson. Munson actually traveled to the West Coast from October to November, and in addition to obtaining information from the Federal Bureau of Investigation and Naval Intelligence, he interviewed Japanese Americans and people who knew Japanese Americans, and compiled his report. This was just one month before the attack on Pearl Harbor. His conclusion was that "Japanese Americans were loyal to the United States and did not pose a threat." 5

Note

1. Densho (Traditional Japanese Legacy Project): The Japanese American Legacy Project is a non-profit organization founded in 1996 by Tom Ikeda, a third-generation Japanese American. It preserves the testimonies of Japanese Americans who were unjustly sent to internment camps during World War II before their memories fade, and makes them available online along with historical photographs, documents, and teacher's materials. Densho's interviews are fascinating because you can see the facial expressions of the speakers, making it feel like you are actually listening to them. http://www.densho.org

2. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

Henry was propagandized because he blindly accepted the Americanization education that taught immigrants English and American culture so that they could quickly get used to life in America. The more successful the school programs were, the more the children had to abandon their Japanese culture. Realizing the harm of this, education has now shifted from a monocultural American culture to one that values multiple cultures.

3. Yoshiko Uchida, translated by Kazuo Hatano, "People Driven to the Wilderness: Records of a Japanese-American Family During the War," Iwanami Shoten, 1985

4. Henry Miyatake, interview by Tom Ikeda, March 26, 1998, Densho Visual History Collection, Densho.

5. http://encyclopedia.densho.org/Munson_Report/

*Reprinted from the 133rd issue (April 2013) of the quarterly magazine "Children and Books" published by the Children's Library Association.

© 2013 Yuri Brockett