Starting with the Great Northern Railway

Montana, which is separated from Canada by a straight border to the north, is bordered by three states: North Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and Idaho to the west. "Centennial History" begins with a general introduction that "It is not clear how Japanese people first came to Montana, but it is said that between 1884 and 1890, as many as 30 Japanese prostitutes came to the mining town of Butte. However, they came in large numbers in 1898, when the Oriental Trading Company signed a contract with the Great Northern Railroad Company to supply Japanese workers and sent a large number of them to the state." The introduction spans 10 pages.

Below, we will summarize some interesting points.

As with Wyoming, which I introduced last time , Japanese workers were sent in large numbers to Montana by Japanese labor agencies to work on the railroad construction that was underway at the time.

As their numbers increased, a community was formed, and in the 1900s, Japanese businesses such as stores were established. In a survey conducted in August 1907, there were 1,920 Japanese in the state, of which 1,630 were railroad workers, making up the majority. There were also only 22 women, making for a skewed composition.

Railroad construction eventually waned, and the demand for railroad workers decreased accordingly. Some workers were forced to leave the railroad and turn to agriculture, just like in Wyoming.

"It all began in 1906 when the Great Western Sugar Company was founded in Billings and, in cooperation with Yusaku Kubosawa, Tsuyoshi Ogoe and others, they signed a contract to supply Japanese workers to radish orchards in the UK, employing over 200 people."

The influx of agricultural laborers continued after that, and some Japanese people who had gained confidence from radish farming began to take out loans from sugar companies and banks to start their own farms. Around 1940, 21 households were engaged in agriculture, and they continued to cultivate vegetables, sugar beets, beans, etc., both during and after the war.

Something like a Wild West

In Montana, anti-Japanese sentiment was intense, and when railroad workers first arrived, clashes arose between them and white workers everywhere. Anti-Japanese land laws were also enacted, and some Issei bought land in the name of Nisei, continued to farm on leased land, or went out of business.

Great Falls, a large city east of the Rocky Mountains and an important railroad crossing point, has long been known for its exclusion of Asians. In 1890, three Chinese men who had started a laundry business were attacked, and two of them were thrown into a waterfall and killed.

Japanese workers who entered later were also attacked.

"A man was attacked by cowboys, taken into the mountains of Wolf Creek, hung from a tree with a thick rope, and when his complexion began to change color, he was let down and tortured."

In Harbor City, fierce fighting broke out.

"In 1903, in the town of Chester, 60 miles west of the city, a major clash occurred between Japanese and cowboys, with hotheaded young Japanese men and rough cowboys engaged in street fighting and shootouts straight out of a Western movie."

Contributions of Dr. Hideyo Noguchi

In Missoula, in the west near Idaho, immediately after the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, "approximately 1,000 people from the central mountain area to the Pacific coastal states who were rounded up as enemy foreign leaders were detained until March of the following year."

Yellow fever broke out in this region, including Mizora, and many Japanese people died of the disease. Because the cause of the disease was unknown, the local medical society invited Dr. Hideyo Noguchi, who was at the Rockefeller Institute in New York, to investigate the disease. He discovered the cause and also invented a vaccine.

However, perhaps due to fears that it was a new drug, no one tried the vaccine at first. However, once the first injection was administered, many others followed suit. As a result, the death rate from yellow fever dropped dramatically, and Dr. Noguchi was praised in the region.

Becoming responsible for prisoner laborers

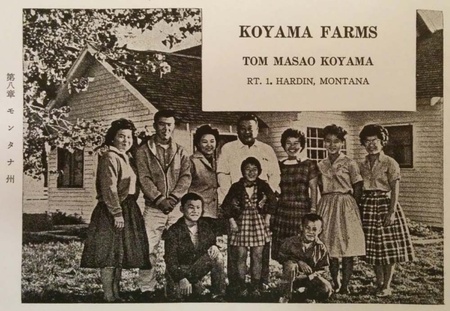

Four people are mentioned in the "Genres of Montana" (personal histories). All of them are engaged in agriculture. Among them, Tom Masao Koyama, a second-generation farmer from Hardin City, has a unique background.

His father was from Wakayama Prefecture and worked for the railroad before moving to farming. Masao moved to Gilmore, California with his parents, and at the age of 19, he was the first to successfully cultivate sugar beets there. In 1937, he went to Japan to attend college, and returned to the United States in 1941 just before the outbreak of war. During the war, he was incarcerated in an internment camp in Arizona.

"(So) he noticed the shortage of farm laborers in Montana, made a sign in both Japanese and English saying that farm laborers were needed in Montana, and collected signatures. About 300 people quickly gathered, so he let the Holly Sugar Company know that he had labor available. With the help of the company, arrangements were soon made for him to go to Montana to work, and he worked hard as the person in charge of the German prisoner of war laborers, just as he had done for the Japanese."

A photograph of the Koyama family published in the Centennial History shows the whole family smiling in front of their American-style home, making them look like a typical American family.

(Note: I have used the original text as much as possible, but have made some edits. In addition, I have based the names of places on the way they are written in the "Centen-nen-shi.")

* Next time we will cover "Japanese Americans in Utah."

© 2015 Ryusuke Kawai