Read Part 3 >>

Stories Involving Zen Life and Poetry

The stories told here about the life of Zen Buddhists and others in the Heart Mountain Relocation Center revolve around Reverend Nyogen Senzaki. He was well known as a Zen priest, scholar, and translator of writings in various oriental languages into English (see Shimano, Chayat, and Reps). He was also known for his poetry and calligraphy. During Relocation, he was very active in the life of the Buddhists, performing funeral services and such; he also wrote poems about life in the center and commemorative poems for major Buddhist holidays.

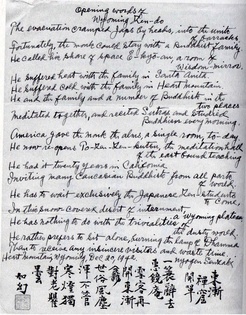

Zen Buddhists did not meet in large halls as did the earlier discussed organized Buddhist Churches. Soon after Senzaki arrived in Heart Mountain, he established a Zen-do1 in a small apartment room he shared with a Block-2 family. There he observed the daily Zen rituals with other Zen Buddhists. Figure 16 shows his “Opening words of Wyoming Zen-do,” a signed and stamped commentary, which he wrote in kanji, and accompanied with his English translation,2 which has been transcribed here.

Opening words of Wyoming Zen-do

The evacuation cramped Japs by heads, into the units of barracks.

Fortunately, the monk could stay with a Buddhist family.

He called his share of space E-kyo-an, a room of wisdom-mirror.

He suffered heat with this family in Santa Anita.

He suffered cold with this family in Heart Mountain.

He and the family and a number of Buddhists in the two places

Meditated together, and recited Sutras and studied Buddhism

every morning.

America gave the monk the alms, a single room, to-day.

He now re-opens To-Zen-Zen-kuten, the meditation hall of

the east bound teaching

He had it twenty years in California

Inviting many Caucasian Buddhists from all parts of the world.

He has to wait exclusively the Japanese Zen-students to come,

In this snow-covered desert of internment, a Wyoming plateau.

He has nothing to do with the trivialities of the dusty world.

He rather prefers to sit alone, burning the lamp of Dharma

Than to receive any insincere visitors and waste time.

Heart Mountain Wyoming, Dec 20, 1942. Nyogen Senzaki

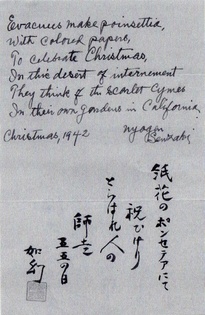

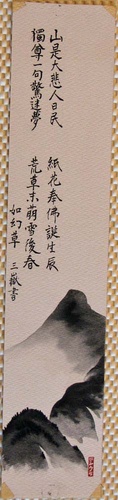

Five days later he wrote, in kanji, a poem3 for Christmas 1942. As shown in Figure 17, the poem is signed and stamped, and includes his English translation (transcribed below). Note that he describes the making of paper flowers for Christmas Day to remember better days.

Evacuees make poinsettias,

With colored papers,

To celebrate Christmas,

In this desert of internment

They think of scarlet cymes

In their own gardens in California.

Christmas 1942 Nyogen Senzaki

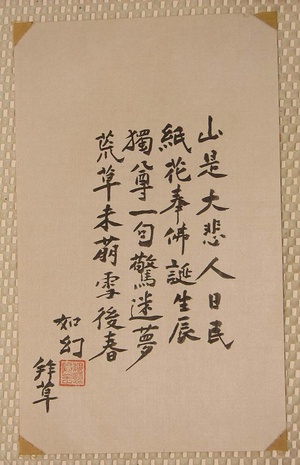

Senzaki was an excellent calligrapher, as can be seen in the Christmas poem, writing his poems with sumi ink. He often gave gifts to friends. For example, he gave his calligraphy of a poem celebrating Buddha’s Birthday on April 13, 1943 – signed and red-stamped by Nyogen Senzaki – to Shingo Nishiura (Figure 18). Shingo and Senzaki lived very near each other and ate in the same mess hall in Block-2, becoming good friends and exchanging many gifts. Interestingly, the date on the poem is a year after the start of his relocation; March 27, 1942, was the official opening date of the Santa Anita Assembly Center mentioned in Figure 16.

Senzaki also translated his poem into English4 on April 13, 1943:

Sons and daughters of the Sun are interned

In a desert plateau, an outskirt of Heart Mountain,

Which they rendered the Mountain of Compassion

or Loving-kindness.

They made paper flowers to celebrate Vesak, the birthday

of Buddha.

“Above the heavens, beneath the earth, I alone am the World-

Honored One,” said the baby Buddha,

Declaring the spirit of independence and self-respect of each

sentient being of the world.

Hey! You! Stupid sagebrush and timid cactus!

Why don’t you stretch out your green buds to answer the call of

spring?

Note that he again refers to making paper flowers in celebration. Perhaps the winter-time sagebrush and cactus symbolize the internees living the harsh, disorienting life of Relocation, whose springtime greening will come through Buddha.

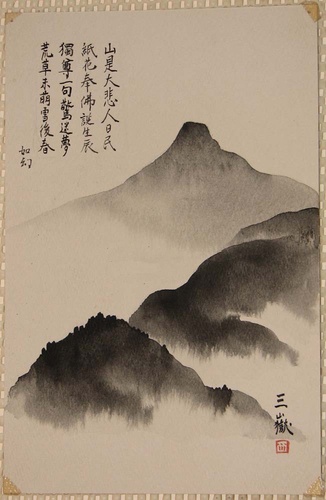

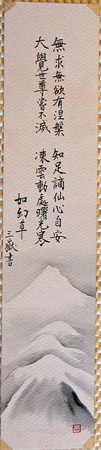

Shingo Nishiura made two sumi drawings – signed with his artist name, Sangaku, and red-stamped – containing Senzaki’s poem (Figures 19a and 19b). There is also in the Shingo Nishiura Portfolio5 a photocopy of a sumi drawing, using the format of Figure 19a, that contains this poem and a view of the Heart Mountain Relocation Center (see Appendix A). The whereabouts of the original of this drawing are not known; perhaps it was given to Nyogen Senzaki.

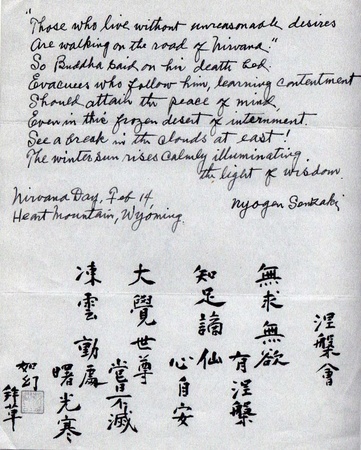

Figure 20 is a sumi drawing by Shingo Nishiura containing another poem by Nyogen Senzaki – written for Nirvana Day, February 14, 1943 – which is also signed Sangaku and red-stamped. A copy of Senzaki’s original of this poem6 is shown in Figure 21. In this poem, Senzaki urges the internees to see the meaning of a rising winter sun. His translation has been transcribed below.

“Those who live without unreasonable desires

Are walking on the road of Nirvana.”

So Buddha said on his death bed.

Evacuees who follow him, learning contentment

Should attain the peace of mind,

Even in this frozen desert of internment.

See a break in the cloud at east!

The winter sun rises calmly illuminating the light of wisdom.

Nirvana Day, Feb 14,

Heart Mountain, Wyoming Nyogen Senzaki

Nyogen Senzaki departed from the Heart Mountain Center in September 1945 to return to the Los Angeles area and re-established his pre-war Zen-do. Shingo Nishiura left the center in August 1945 to manage the WRA-sponsored Mountain View [California] Hostel for returning internees; his family joined him a month later.

The Senzaki calligraphy of his poem and the three Nishiura sumi drawings (Figures 18, 19a, 19b, and 20) are from the Shingo Nishiura Portfolio. The other figures are taken from Shimano and Chayat, where many other images and translations of Senzaki’s works can be found. The images and translations give a feel for the life of Zen Buddhists during Relocation.

As an aside, before Relocation, Shingo had attended the Japanese Methodist Missionary Church in Mountain View, California; his father, uncle, and his father’s aunt were of the Shingon Buddhist sect; his mother and wife were of the Nishi Honganji Buddhist sect; and his brother married into a Japanese-speaking Catholic family in Los Angeles – all of them were immigrants relocated to the Heart Mountain Center. Senzaki was the same age as Shingo’s father and could read, write, and speak English; Shingo and his brother also learned to read, write, and speak Engish, as many young immigrants did.

70 Years Later

Many changes occurred after the war with Japan ended with a bang. “No-No” Japanese immigrants and their minor children, “declared disloyal,” were deported to Japan. The eastward relocation was reversed. The McCarran-Walter Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1952 became law; many surviving Japanese immigrants of the Relocation became U.S. citizens; immigration resumed after decades of denial.

Those born in the Relocation centers are now in their 70s. Only a few young adults of the Relocation are still alive – and the passing of the teenagers and young children of the Relocation is just beginning. All the Japanese immigrants named in this article have passed away. Indeed, all relocated adult Japanese immigrants, about 40,000 of the 120,000 internees, are at least 90 years old, or have passed away. Many life-experiences during Relocation of these Japanese immigrants will never be told. By themselves, altars and calligraphies in museums or preserved as photographic images will not tell the context of how immigrants made them, how immigrants reacted to them, or how they met religious needs of internees during Relocation. With a little bit of imagination, the stories told here can help. Put in the spirit of Zen calligraphy: Hey! You! Silent beautiful objects! Why don’t you stir imaginations to bring life back as Relocation is more than 70 years old?

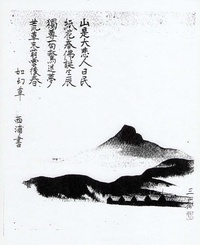

Appendix A: The Lost Shingo Nishiura Drawing

Figure 22 is a photocopy of a sumi drawing of the Heart Mountain peak and a row of barracks in the foreground. The poem is the one by Senzaki in the calligraphy (Figure 18) gifted to Shingo Nishiura. In the drawing, the column to the left of the poem translates as “Senzaki author,” “Nishiura writer.” On the bottom right is Sangaku (written in kanji), Shingo’s artist name, and his stamp with the first kanji character of his two-character surname nishi and ura. The signature Sangaku indicates that Shingo was very satisfied with the drawing. The message of the poem as translated by Senzaki is beautifully conveyed in the drawing – Heart Mountain’s peak floating in the background, the plateau with the dark unforgiving barracks of the Center, and the unseen sagebrush and cactus asleep. The friendship between Senzaki and Shingo can be discerned from this drawing.

Appendix B: Altars From Other Relocation Centers

Buddhist altars were also built in other Relocation centers. Two were discussed in the 2005 book The Art of Gaman: Arts and Craft from the Japanese American Internment Camps, 1942-1946, by Delphine Hirasuna. These altars, along with two others, were included in the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Renwick Gallery Exhibit of 2010 with the same title – Hirasuna was the guest curator for the 2010 exhibit. The exhibit subsequently toured the United States and went to Tokyo, Japan. One of the four altars in the exhibit was the already-discussed Bishop Obutsudan. A brief discussion of the other three altars is next.

The Rowher Relocation Center Altar

This altar (Figure 23) appeared in Hirasuna’s book.7 As stated in the book, it was made by Shintaro Onishi, a farmer from Lodi, Califonia, while he was in the Rowher Relocation Center, and its dimensions are 16 by 18 ¾ by 7 inches. Unlike all of the altars discussed earlier in this article, this altar was made from a firewood log. Onishi hollowed out the log, attached hinged doors, and roofed it with the bark of the log. The resulting altar is a work of art. Onishi did not use cured wood as in the earlier discussed altars, and during the 70 years after Relocation it slowly dried out and began showing cracks; it was withdrawn from the traveling exhibit to avoid damage.

The Santa Fe Internment Camp Altar

This altar (Figure 24) also appeared in Hirasuna’s book.8 The maker is Mineo Matoba. On December 7, 1941, he was forcibly relocated to the Santa Fe Justice Department Internment Camp (essentially a prisoner of war camp), in New Mexico.9 The altar consists of six pieces of carved wood for easy assembly and dismantling. Its dimensions are 9 by 12 ½ by 9 inches. There is no information about the tools that Matoba used. According to Hirasuna [p. 105], the altar was shipped to Matoba’s wife, who was relocated with her family to the Gila River Relocation Center in Arizona. He was eventually released from the Santa Fe Camp and relocated to Gila River Center.

The Granada [Amache] Relocation Center Butsudan

This butsudan was in the Smithsonian Exhibit but did not appear in Hirasuna’s book. The slideshow for the exhibit included two views of the butsudan, which have not been reproduced here. According to the slideshow, the altar was made by Kichitaro Kawase in the Granada [Amache] Relocation Center in Colorado, and the exhibit description says that the butsudan is made from scrap wood that has been painted and includes metal parts.10 The butsudan, in the slideshow images, appears to be about 30 inches tall and 24 inches wide; the depth cannot be estimated from the images. Archival records11 show that Kawase was a farmer, not an artisan.

Notes:

- Zen-do is a place for Zen meditation (Shimano, page 197).

- See Chayat, page 328.

- See Chayat, page 329.

- See Shimano, page 21, for the April 13, 1943, poem.

- The Shingo Nishiura Portfolio is in the Nishiura Archives.

- See Chayat, page 334.

- See Hirasuna, page 105, for the image and the information about the altar.

- The image is from Iowa State U. See Hirasuna, page 105, for another image and the information about the butsudan.

- For information on this camp and other such camps see NJAHS, page 27.

- This is taken from information provided in the slideshow.

- See AR1 and AR2, search for Kawase.

References

[AR1] Archival Records: WW2 Japanese Relocation Camp Internee Records. www.JapaneseRelocation.org

[AR2] US Archival Records: The National Archives. http://aad.archives.gov/aad/series-description.jsp?s=623&cat=WR26&bc

[AR3] Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation Archives. www.heartmountain.org

[BCA] Buddhist Churches of America, Volume 1, 75 Year History 1899-1974. Chicago. Norton Inc., 1974.

[Chayat] Chayat, Roko Sherry, editor. Eloquent Silence: Nyogen Senzaki’s Gateless Gate and Other Previously Unpublished Teachings and Letters. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2008.

[GR] Gesensway, Deborah and Mindy Roseman. Beyond Words: Images from America’s Concentration Camps. Ithaca NY: Cornel University Press, 1988.

[Hearn] Hearn, Lafcadio. Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan. Tokyo: Tuttle Company, 1990.

[Hirahara] Hirahara, Naomi. “Japanese American National Museum, Master Artisans of San Jose: The Nishiura Brothers,” Discover Nikkei, April 28, 2014. www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2014/4/28/maser-artisans-san-jose (originally appeared in Japanese American National Museum Member Magazine, Winter 2000).

[Hirasuna] Hirasuna, Delphine. The Art of Gaman: Arts and Crafts from the Japanese American Internment Camps 1942-1946. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press, 2005.

[HMCC] Heart Mountain Carpenters Club Directory. Washington State University, WSU Libraries, Digital Collections.

[Iowa State U] Online Center for the Study of Japanese American Concentration Camp Art, Iowa State University. www.lib.iastate.edu/internart-main/2023/3007 .

[Ishigo] Ishigo, Estelle. Lone Heart Mountain. Los Angeles: Ishigo, 1972.

[Kashihara] Kashihara, Kazuo, editor. A History of Japanese Religion, translated by Paul McCarthy and Gaynor Sekimori. Tokyo: Kosei Publishing Company, 2002.

[Masuyama] Masuyama, Eiko Irene. Memories: The Buddhist Church Experience in the Camps, 1942 – 1945. Revised edition. 2004.

Masuyama, Eiko Irene. Memories: The Buddhist Church Experience in the Camps, 1942 – 1945. Second revised edition. 2007.

[NJAHS] Americans of Japanese Ancestry and the United States Constitution, 1787 – 1987. San Francisco: National Japanese American Historical Society, 1987.

[PMCA] South, Will, Marian Toshiki-Kovinick, and Julia Armstrong-Totten. A Seed of Modernism: The Art Students League of Los Angeles, 1906-1953. Pasadena Museum of California Art. Berkeley, California: Heyday Books, 2008.

[Reps] Reps, Paul, compiler. Zen Flesh, Zen Bones: A Collection of Zen & Pre-Zen Writings [transcribed by Nyogen Senzaki]. Rutland, Vermont: Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1958.

[Sakauye] Sakauye, Eiichi Edward. Heart Mountain: A Photo Essay. San Mateo, California: AACP, Inc., 2000.

[Shimano] Shimano, Eido, editor. Like a Dream / Like a Fantasy: The Zen Teachings and Translations of Nyogen Senzaki. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2005.

[SH] Spahn, Mark, Wolfgang Hamaitzky, and Kimiko Fujie-Winter. Japanese Character Dictionary with Compound Lookup via Any Kanji. Boston: Cheng & Tsui Company, 1989.

[SJSCB]San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin. 1902-2002, Our First Hundred Years: San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, San Jose, California. San Jose, California: Centennial Yearbook Committee, 2003.

[WRA] War Relocation Authority, Heart Mountain Center, Cody, Wyoming. TecCom Productions, 1990.

© 2015 Togo Nishiura