Kakuro’s life in Hawai`i and arrest

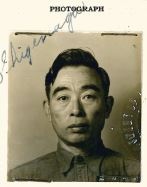

Kakuro Shigenaga was born in the Hibagun district of Hiroshima-ken on August 30, 1896, came to Hawai`i in February of 1913, and settled on Maui. He was a salesman at the Kobayashi General Store in Kahului, Maui and married to Yoshie. They had four children.

Kakuro was arrested on January 7, 1942, one month after Pearl Harbor was attacked, because his diary was found during a search of his brother Shigeo’s house, and the FBI claimed his writings contained anti-American and pro-Japanese sentiments. Grandson Mark Shigenaga said that Kakuro was staying in Honolulu at his brother’s home just as the FBI was making its sweeps. The purpose of this visit was to plan the moving of Kakuro’s family from Maui to Oahu. Once moved, the two brothers were planning on having Kakuro manage a store, a venture financed by Shigeo and his attorney friend.

During his hearing, Kakuro said through a translator that he shouldn’t have written anti-American sentiments, that “it was foolish because you keep things for a while and then you pitch them aside and they are worthless.” When questioned who he would like to see win the war, he replied, “I am earnestly desirous of peace.” He agreed with his questioner that the attack on Pearl Harbor was “a treasonable matter of doing, very pitiful.”

Needless to say after his diary was found, Kakuro’s fate was sealed. He was ordered to be interned on February 17, 1942. The board said that 1) he was a subject of the Japanese empire; 2) he was disloyal to the U.S.; and 3) there was indirect evidence to substantiate a finding that “the internee was involved in subversive activities.” This evidence, if it existed, was not part of his file. Kakuro’s son Winston noted that before the war, a Japanese maritime training ship was visiting Maui and Kakuro hosted several sailors at the family’s home. This could have been interpreted as a subversive activity.

Shigeo’s life in Hawai`i and arrest

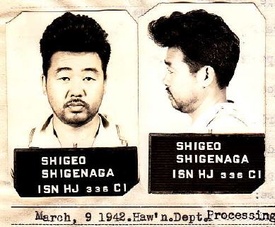

Brother Shigeo Shigenaga was born on March 14, 1901 in Hiroshima-ken. He came to Honolulu in February of 1917 and was the manager of the Venice Café, which his wife Akino owned.

Shigeo’s son Paul was born in 1942 after his father was taken away and his mother did not have his help during her pregnancy and delivery. Shigeo and his wife Akino had four sons and a daughter. Paul says the family recounts the reason for the arrest of both brothers as follows:

“When the family was residing in Nuuanu [a residential area in Honolulu], it just so happened that your grandfather [Kakuro] was at our home when the police came looking for my father [Shigeo] who was involved in various Japanese activities. The police asked who is ‘Mr. Shigenaga’ and your grandfather said, ‘I am’ so they hauled him to Sand Island in Honolulu where they were holding the Japanese Issei [first generation] detainees. Then they found out that they got the wrong Shigenaga, so they came back later to the house to wait for my father and arrested him when he arrived home. Since they already had detained your grandfather and knowing that he was my father’s brother and also an alien like my father, they also decided to retain him in custody.”

According to documents in the files of the National Archives in College Park, MD, the FBI said Shigeo “is prominent in Japanese circles and is pro-Japanese.” The FBI said he had photographs of high Japanese naval officials and was a camera enthusiast.

During questioning on March 7, 1942 by a military-civilian board, Shigeo said he would fight for the United States against Japan, and the Japanese flag he had at his home was a gift. He was questioned about his associations, books in his possession, etc. Shigeo noted, “I cannot understand why I come down here, because I am living 25 years in Hawaii. My father die here. My brother, my sister, all family here. I have got five children all American citizens… This is the place for me. I would die in Hawaii. My home is here. That’s why I buy, just before December 7. I buy a home.”

His attorney, John Gilliland, spoke on his behalf, and said in response to comments by the board that reputable Japanese had said he was “unscrupulous in business, of loose morals, and is pro-Japanese,” that other Japanese were jealous of Shigeo’s business success which is why they may have badmouthed him.

Shigeo continued, “President Roosevelt…said that all people should be allowed to go about their work and have freedom as long as they were law abiding citizens. I did nothing wrong…and I truthfully can say that I pay my allegiance to America.”

The board ultimately decided to intern Shigeo for the duration of the war because they said he was loyal to Japan, was a photographer, and friendly with a Shinto priest in Honolulu. During his internment, his wife Akino ran the Venice Café in his absence.

Journey to Angel Island

Hawaiian detainees were usually first briefly detained at the Immigration Station in Honolulu, then Sand Island. From there, many of them boarded ships for the mainland. Kakuro was detained on Sand Island in the Honolulu harbor and, according to his documents in the National Archives, boarded a ship for the United States with the first group of Hawaiian detainees on February 20, 1942. He was detained on Angel Island from March 1 to 9, 1942. Shigeo was also detained on Sand Island, then Angel Island from June 1 to 4, 1942.

Shigeo was interviewed by Patsy Sumie Saiki and his account of his journey to Angel Island on the U.S.S. Ulysses S. Grant was documented in her book Ganbare! An Example of Japanese Spirit. Saiki noted that boarding the ship, “Young men like Shigeo Shigenaga and Rev. Kenjitsu Tsuha helped the older and weaker by tying two duffel bags and swinging one pair over each shoulder.”

Saiki noted that what made the internees miserable on the ship was that “they were locked, eight or ten in a room, for three hours at a time. At the end of three hours, the door was unlocked and a guard escorted the men to a makeshift oil barrel latrine. Then it was back to the locked room. It was continued days of humiliation and suffering, especially for those with bladder problems.” The U.S.S. Ulysses S. Grant snaked its way across the Pacific, avoiding Japanese submarines, and after ten days finally reached San Francisco Bay on March 1, 1942.

Saiki wrote that the detainees were transferred into small tugboats and “did not mind being photographed, fingerprinted, and examined in the nude for ‘infectious diseases.’ This took from 9 p.m. to 6 a.m. and it was cold, a damp clinging cold. After their clothes and duffel bags had been examined, they were each given two blankets and told to go upstairs to rest. It seemed like they were back at the Immigration Station in Honolulu, but now when they took a hot shower, used the toilet, or did their laundry, these simple acts were indeed luxuries.”

“Like the Immigration Station in Honolulu, this one had three-tiered bed-shelves lining the walls. Men also slept on their blankets on the floor. They were so crowded, 140 to a room, that they could hardly move.” Detainees brought their concerns about the overcrowded conditions to an official, who explained that the Army had sent too many internees at one time and there was nowhere else to house them. The detainees were to stay on Angel Island for only a few days, anyway.

After Angel Island

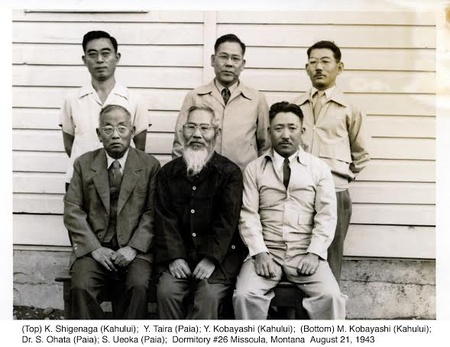

After Angel Island, Kakuro went on an odyssey which took him to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin in March of 1942; Camp Forest, Tennessee in May 1942; Camp Livingston, Louisiana in June of 1942; Fort Missoula, Montana in June of 1943; Santa Fe, New Mexico in April of 1944; and finally back to Hawai`i via Seattle in November of 1945. While at Fort Missoula, he petitioned to not have his family join him (at that time, Mark’s father, Winston, Kakuro’s eldest son, remembered his mother talking about it, and that she couldn’t travel due to her poor health).

Grandson Mark Shigenaga told a story related by Winston. “Apparently, Kakuro was very friendly and close to the head of the Fort Missoula Detention Camp. He was invited on several occasions to have dinner with this Caucasian man and his family. Who would have ever thought that that would be possible during wartime!” After the war, Kakuro kept in touch with this family and would send them Christmas gifts.

When he was detained at Santa Fe, Shigeo was the signer of a letter to the Provost Marshal General as the spokesperson for 270 Hawaiian internees who wished to be transferred to the internment camp in Hawai`i. In the letter, he describes several groups, including fathers of U.S. soldiers or those about to be called into the service, and those who wish to be reunited with their families on the mainland, as well as a group who wished to be repatriated to Japan. Although the authorities did not take immediate action, Stephen Fahrand of the Provost Marshal General’s Office stated that the office was considering such actions for those with sons in the armed forces. Both Shigeo and Kakuro’s children were too young to be affected by such actions.

After several days on Angel Island, Shigeo was sent to Fort Sam Houston, Texas at an unknown date, then Lordsburg and Santa Fe, New Mexico, both in June of 1943. He, too, returned to Hawai`i via Seattle in November of 1945 and likely traveled with his brother Kakuro.

After the War

Upon his return from internment, Kakuro pumped gas at a service station until he opened up a small family-operated grocery store. From his experience with Kobayashi General Store, he resumed his sales route in Wailuku, while his wife Yoshie worked in the store and four children took care of wholesale deliveries. He expanded his business by becoming the island of Maui wholesale distributor for many food items from neighboring islands (e.g. kimchee from Kohala, gobo (burdock roots) from Kamuela, Maebo saimin (noodles) and wonton chips from Hilo, kamaboko (fish cakes) from Hilo and Honolulu).

He encouraged his children to live on the mainland. All four of his children left Maui about ten years after the end of the war and settled in the Los Angeles area. Kakuro passed away in 1968 at the age of 71 and Yoshie in 1991 at the age of 87.

According to an article in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser, “Opening beachfront hotel was ‘man’s biggest dream,’” after Shigeo returned to Honolulu from the camps, he resumed running the Venice Café until the early 1950s. He then moved the family to the beach and, in 1954, opened the Hotel Kaimana.

One of Shigeo’s favorite pastimes was cooking, and he decided to open an authentic Japanese teahouse and garden on the property. “The teahouse was built by Japanese carpenters with tatami floors and was named Miyako,” his son Paul noted. “Many celebrities such as Frank Sinatra and Rita Hayworth enjoyed the atmosphere and fine Japanese cuisine cooked by a chef from Japan with our father and mother assisting.” When the hotel’s nine-story tower opened in 1964, more than 1,000 guests attended the grand opening, son Fred told reporter Bob Sigall.

“This is the happiest moment in my life,” said Shigeo. “My biggest dream has been completed. This magnificent hotel will be the central meeting place of the East and West and will play a big role in the furtherance of goodwill between the U.S. and Japan,” the Hawaii Hochi quoted Shigeo in its coverage.

“In September 1947, when trade was reopened between the U.S. and Japan, Shigeo was invited to Japan with the first group of buyers from Hawaii,” his son Paul said. During this trip he became the first foreign resident after World War II to receive the honor of a personal meeting with Emperor Hirohito at the Imperial Palace.

“In 1954 he was the first foreign resident to receive the Distinguished Black Ribbon Medal (from) the Japanese government after World War II. He was nominated by his Hawaii colleagues to receive the Emperor’s Order of the Rising Sun award, but he turned it down because he always felt that the person receiving the award should be highly educated and he was not,” according to Sigall. Businessman and philanthropist Charles Reed Bishop and Senator Daniel Inouye were both given this award.

Shigeo Shigenaga died in 1984 and Akino in 1996.

Sources:

Internment files on Kakuro Shigenaga and Shigeo Shigenaga, Record Groups 60 and 389, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland. Special thanks to Adriana Marroquin for research assistance.

Saiki, Patsy Sumie. Ganbare! An Example of Japanese Spirit. Honolulu, Kisaku, Inc., 1982.

Emails and conversations with members of the Shigenaga family (special thanks to all)

Sigall, Bob. “Opening beachfront hotel was man’s ‘biggest dream,’” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, Oct 03, 2014.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation