The lights flicker once, and people begin to move from the lobby into a long line.

“Why all this drama?” the White woman behind me is asking. “They’ve never done this before, why are they going through our bags now? We have had enough of going through security.”

The Seattle Opera staff member, dressed in a sober maroon jacket, answers her. “It’s part of the pre-show experience,” she says. I look ahead to the long table, the security guards in black uniforms, the whitewashed picket fence, the barbed wire in front of the exhibits, and suddenly I know.

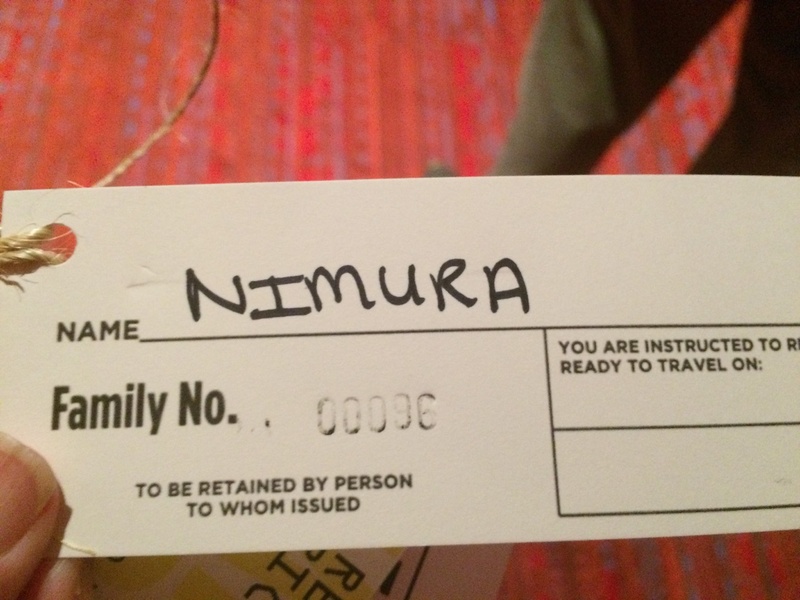

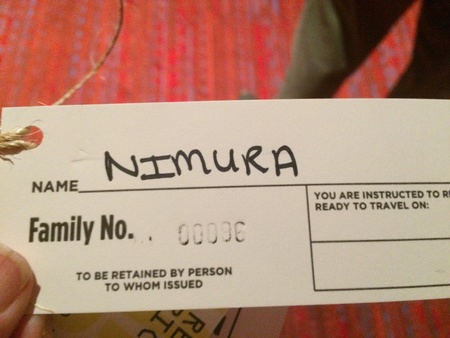

“Oh, no,” I say. “We’re getting tags, aren’t we?”

The staff member opens and closes her mouth, raises her eyebrows, says nothing. Nods, grimly.

Ahead of me, I see an older Japanese couple writing their names on tags, and obediently slipping the twine on around their necks. My heart breaks, a little. My hands are shaking a bit as I pick up the black Sharpie and write NIMURA on the tag. The guard inspects my tag, asks me a couple of questions, tells me I can go in.

This is how I’m herded—deliberately—into the “pre-show immersive experience” of Seattle Opera’s recently commissioned chamber opera, An American Dream.

* * * * *

An American Dream is a story of two families, one Japanese American and one Jewish American, during World War II. When the Japanese American family is forced to leave their farm for “evacuation,” the Jewish American family buys it. Both families have secrets that bind them to each other and are eventually revealed.

The score was written by California composer Jack Perla and the libretto by one of Seattle Opera’s communications staff, Jessica Murphy-Moo. The opera was commissioned as part of the Opera’s “Belongings” project, where audience participants were asked, “If you had to leave today and could not return, what would you take with you?”

According to the International Examiner, Murphy-Moo worked partly with Gabrielle Kazuko Gainor, a member of the Opera’s communications staff (and active JACL member), as well as Mary Matsuda Gruenewald, a local Nikkei resident from Vashon Island, in order to provide as much cultural and historical authenticity as possible. Notably, the opera gave several community previews and from several accounts demonstrated outstanding community engagement, both in outreach and attendance.

* * * * *

As for the opera itself, there are some striking aspects. The vocal performances were all strong and I hope to see more of each actor. The projected computer animation that serves as visual accompaniment to the prelude is beautiful and I would have loved to see more of it towards the end. The staging is effective, using the farmhouse table as the main source of connection between the two families and the two stories. I missed more familiar musical elements of classical opera, such as melodic motifs that reappear or are keyed to a character.

Given the evening’s pre-show (and marketing) emphasis on Japanese American history, it struck me as a little strange that the high dramatic point of the opera was the main Jewish character’s discovery of her parents’ fate, rather than the fate of the Japanese mother in camp. I also wondered a bit at the main Japanese character’s treatment of the Empress doll, which struck me as more of a plaything (as in Western doll culture) rather than a ceremonial doll—it didn’t seem to fit what I’d been taught about the purpose of matsuri dolls.

Nevertheless, it’s laudable that the Opera and its staff used research and community engagement to showcase these important local histories and to think about the possible intersections of wartime narratives.

After the opera, though, I’m still thinking back to the pre-show experience.

* * * * *

We walk ahead to a darkened hallway, this time with a highlighted timeline of social justice events in Seattle. There’s another long line of people, and another set of guards there. “Keep moving,” he keeps telling us. Off to the left, I can see the gift shop, an odd contrast with the television screen nearby showing a documentary about Japanese American incarceration.

Farther down the hall, near the elevator, the signs warn us that the next exhibit is filled with racist imagery. Those who wish to skip this portion of the exhibit, the sign informs us, can take the elevator.

The next exhibit has dramatic uplighting, and it shows newspaper ads and racist signage and propaganda from the time. A few people are staying to read the literature. I’ve seen much of it before, however, and I walk upstairs to the lounge.

Inside there’s already a hundred people or so walking around. It, too, has been transformed. There are familiar green velvet lounges, and people buying cocktails and coffee from the bar. But there are more exhibits and more television screens with documentaries. And there’s a whitewashed barrack, with cots and more armed guards. People are sitting around on the velvet couches, but some of them go over to the cots. The guards are still brusque. “Don’t touch anything, it’s for your own safety,” they tell these people. “The walls are whitewashed.”

I’m reeling as I walk around and look at the exhibits. Some are from Jewish American historical groups, such as the Holocaust Center for Humanity.

I see the older Japanese woman from the couple ahead of me in line. I walk up and introduce myself. Her name is Naomi Minegishi, and she tells me that she and her husband moved to the United States from Japan in 2000. “May I ask you why you are wearing the tag?,” I say gently. She pauses. “We are trying to experience what they went through,” she explains. Her husband was involved in conveying camp history to people in Japan, she tells me. “Not many Japanese knew about the history here.” I thank her, and try to explain why I’m so shaken. “My father and his family were in camp. All of this is”—my hands gesture around the room, helplessly—“difficult for me.”

Eventually, the house lights flicker to signal that it’s time for everyone to take their seats. Because this is the dress rehearsal, there’s a large bank of computers in the middle of the theater. I see faces of people that I know; Lori Matsukawa, the local television journalist; I see Tom Ikeda, director of Densho, who offered me a ticket to this performance. I see Frank Abe, journalist and documentarian, and he introduces me to his daughter. And I see Lilly Kitamoto Kodama from Bainbridge Island, who I’d met last year. As I look around, there are so many Japanese Americans in the house and so many community members. It’s a wonderful sight to see at McCaw Hall, Seattle’s opera house.

The lights dim, and there are three empty chairs at stage right. Three people are escorted to the seats. They introduce themselves as Lilly Kitamoto Kodama, Felix Narte, and Kay Nakao, all from Bainbridge Island. Because they are important members of local history, it’s moving to hear them tell their stories, even briefly. Kay makes the audience laugh as she tells us when she was born, “a long time ago.” She tells us about her father’s restaurant, that “heart and soul, he was really an American.” Felix is Filipino (like me), and his father took care of one of the Japanese American farms while the owners were in camp. When the owners returned, they gave him—and his voice chokes up in retelling this part of the story—part of the farm in thanks for his service. Lilly’s voice is strong and clear. “I have never met with any racial discrimination on Bainbridge Island,” she says, and applause follows her statement. I wish there was more time and space to hear them talk, but I appreciate that they’re there at all. I wish I could listen to them more.

After the show I walk over to the edge of the balcony. I’d expected documentaries, perhaps, or lectures before the show, but not an experience this immersive. It’s effective, if shattering. And yet, when it comes to camp, perhaps I still find the realities—and the real people—more compelling than the fiction.

I know I’m supposed to put on the tag, but I don’t.

© 2015 Tamiko Nimura