Fans of best-selling author Lisa See will not be surprised by her diverse background, the source of the unique perspective readers inevitably find in each of her novels.

Born in Paris but raised and residing in Los Angeles for most of her life, she is part Chinese. Her great-great-grandfather came to the United States to work on the building of the transcontinental railroad, and her great-grandfather was the “godfather” or “patriarch” of Los Angeles’ Chinatown. About 400 members of her large Chinese American family currently live in the Los Angeles area.

Despite her appearance—red-haired and freckled—Lisa See has always been strongly influenced by her Chinese identity. In a recent interview, the author explained, “I don’t look at all Chinese, but I grew up in a very large Chinese-American family. My Chinese background influences everything in my life. It’s in how I raise my children, in what I eat, in how I remember the people in my family who’ve died. It’s in what I plant in my garden and how I decorate my house. I have a western doctor, but my main doctor is from China and practices traditional Chinese medicine.” Of course, her Chinese heritage is also an integral part of her writing.

See does not set out to educate her readers about Chinese culture; instead, she views her books as a reflection of her own personal journey, a journey in which her culture has played a significant role. “All writers are told to write what they know, and this is what I know. In many ways I straddle two cultures. I try to bring what I know from both cultures into my work. I have no way of knowing if this is true or not, but perhaps the American side of me is able to open a window into China and things Chinese for non-Chinese, while the Chinese side of me makes sure that what I’m writing is true to the Chinese culture without making it seem too ‘exotic’ or ‘foreign.’ In other words, what I really want people to get from my books is that all people on the planet share common life experiences—falling in love, getting married, having children, dying—and share common emotions—love, hate, greed, jealousy. These are the universals; the differences are in the particulars of customs and culture.”

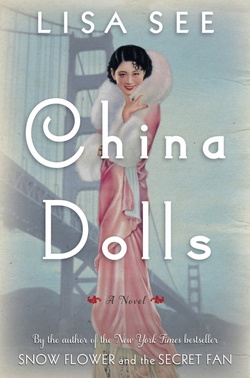

Through these reflections about her writing, Lisa See captures the essence of her latest novel, China Dolls. Within the narrative, the author provides readers with a glimpse into the history of both her own Chinese American heritage as well as the Japanese American experience during World War II. The novel revolves around three Asian American women who meet at an audition at The Forbidden City, a nightclub and cabaret in San Francisco that featured Asian performers from the late 1930s to the 1950s. The three women—Grace Lee, Helen Fong, and Ruby Tom—share the role of narrators, creating a kind of symmetry within the novel which is itself divided into three sections—the Sun, the Moon, and the Truth.

What seems like an impossible feat in narration is masterfully achieved by the author. Embodying the mind of one female protagonist is daunting, yet Lisa See takes on the ambitious task of narrating the story from the points of view of all three distinctly different—and incredibly complicated—women. First, there is Grace Lee, who has come from Plain City, Ohio to California with the small savings she has collected from working at her family’s laundry business. Leaving her mother and her beloved dance teacher behind, she sets out alone to find a new life far away from the physical abuse of her father. Next, there is Helen Fong, the eighth child and only daughter from a patriarchal, traditional Chinese family. Feeling unloved by her father who openly wished for an eighth son rather than a daughter, Helen yearns to do more than simply contribute to her brother’s tuition and live chained to the boredom of her job at the Chinese Telephone Exchange. Last, there is Ruby Tom, whose desire to become famous and whose love of “glitter” bring her to the auditions for The Forbidden City, where she meets Helen and Grace. The narrative chronicles the lives of the three women and their unique struggles as they seek independence, success, and love on their own terms.

According to Lisa See, the idea for China Dolls began with the characters and with the history of nightclubs like The Forbidden City. Elaborating on her inspiration for the novel, she said, “I started with the idea that I wanted to write about three friends. That triangle is so complicated—for men and women! But I’d also been thinking about writing about the Chinese-American nightclub scene of the 1930s and 1940s for years. I have fans who have sent me photos of their mothers, aunts, fathers, and uncles who performed. There were so many great stories. I also felt that if I didn’t do this now, then I might not have a chance to interview some of the earliest performers. I interviewed Dorothy Toy and Mary Ong Tom when they were 93; I interviewed Mai Tai Sing and Trudi Long when they were 88. I count myself very fortunate to have captured their stories and had a chance to experience their humor, courage, and persistence firsthand. Those four women were my greatest inspiration for China Dolls.”

The central characters evolved from those interviews and additional research. “Grace is probably the truest to the performers of those days. She grew up in a small town in Middle America, longing to sing and dance. With Helen I wanted to write about someone who grew up in a very traditional family in Chinatown. What could she have done or what could have been done to her that would allow her family to permit her to dance in a nightclub? With Ruby, I was inspired by Trudi Long and Dorothy Toy, who both had Japanese backgrounds. Their stories really informed what happened to the character of Ruby.”

Like their real-life counterparts, Grace, Helen, and Ruby find their lives fractured by the effects of World War II and particularly by the bombing of Pearl Harbor. What is both unique and compelling about China Dolls is the way in which Lisa See eloquently captures the painful and conflicted experiences of both Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans within her narrative. “Because I grew up in a Chinese-American family, I know a lot more about that experience. But I don’t think the two experiences were all that separate in the sense that Los Angeles was a relatively small city back then, Chinatown and Little Tokyo were geographically closer than they are today so people knew each other, and both groups were minorities that faced different and differing levels of racism, bigotry, and discrimination in the years leading up to the war, certainly during the war, and after the war. With China Dolls, I wanted to write about performers who were Japanese American, who changed their names and basically masqueraded as Chinese Americans so they could perform. These were Chinese-American nightclubs, after all, and what other choices were out there? If you were from a Japanese, Hawaiian, or Filipino background, where could you perform? Not on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Not on the Borsch Belt. And certainly not in a white club. Later, when the war came, the fact that some of these performers had changed their identities protected them.”

Rather than viewing these experiences as disparate and Chinese and Japanese Americans as antagonistic, the author conveys “universals” and “common life experiences” through her characters. While capturing more than one cultural viewpoint in China Dolls was certainly not an easy task, Lisa See brings to light important connections between Chinese American and Japanese American experiences. She observed that, during World War II, “all the negatives that had been out there about the Chinese shifted to the Japanese. Since China and the U.S. were suddenly allies, the Chinese Exclusion Act could no longer stand and it was finally overturned. But that doesn’t mean discrimination against the Chinese disappeared overnight. Chinese in Los Angeles and all along the West Coast—including people in my family—wore buttons saying that they were Chinese, and put signs in the windows of their houses, cars, and businesses to say they were Chinese. This goes to the age-old stereotype about how all Asians look alike. Magazines like Time and Life ran articles pointing out the differences between Chinese and Japanese. So even though the experiences for Chinese Americans and Japanese Americans during the war were completely different, they are also linked by a deeper and older history that goes back centuries, by the ignorance and bigotry they faced, and by the new fear and paranoia brought about by the bombing of Pearl Harbor.”

For further inspiration for her novel, the author drew from her family history as well. “I was also inspired by my grandparents, who took care of the home of the Oki family when they were sent to camp. Most families lost everything—their homes, farms, businesses, cars, personal belongings. But because my grandparents stayed in the Okis’ house, they were able to return to their home once the war was over. I asked my father about this when I was writing the book. Was it dangerous? Were they afraid? My father, who can be a bit flip, answered, ‘The rent was cheap.’ This was important, because my grandparents were going through some tough financial times. But I think it was much more than that. The FBI came to the house on my father’s birthday, because the neighbors thought my grandparents were using the party decorations to signal to Japanese submarines.”

While each reader will most likely take away something different after reading China Dolls, the novel offers a subject of interest for everyone—history, culture, friendship, romance, and even dancing. Ultimately, however, the power of Lisa See’s novel is in the universal truths it conveys. The novel reflects the very real way in which our basic humanity unites us, often transcending the cultural, political, historical, and religious issues that may initially divide us.

Lisa See has written nine books, including six New York Times bestsellers: On Gold Mountain, Snow Flower and the Secret Fan, Peony in Love, Shanghai Girls, Dreams of Joy, and now China Dolls. She is currently working on a new novel, tentatively titled, The Tea Girl of Hummingbird Lane, about mother-daughter relationships, tea and its history, and the Akha ethnic minority of Yunnan province.

On Saturday, January 31, 2015 at 2 p.m., Lisa See will be speaking at the Japanese American National Museum as part of the Books and Conversations series. Free with general museum admission.

© 2015 Japanese American National Museum