“I am constantly struck by how incredibly brave and committed Laura Kina and Emily Hanako Momohara were to this project and for creating work that comes from such a personal space for which the public can experience,” says curator Krystal Hauseur.

Hauseur is reflecting upon Sugar/Islands: Finding Okinawa in Hawai‘i—The Art of Laura Kina and Emily Hanako Momohara, a new exhibition that juxtaposes the work of the two artists. Both artists are fourth-generation American, mixed-heritage women from families with roots in Okinawa and Hawai‘i.

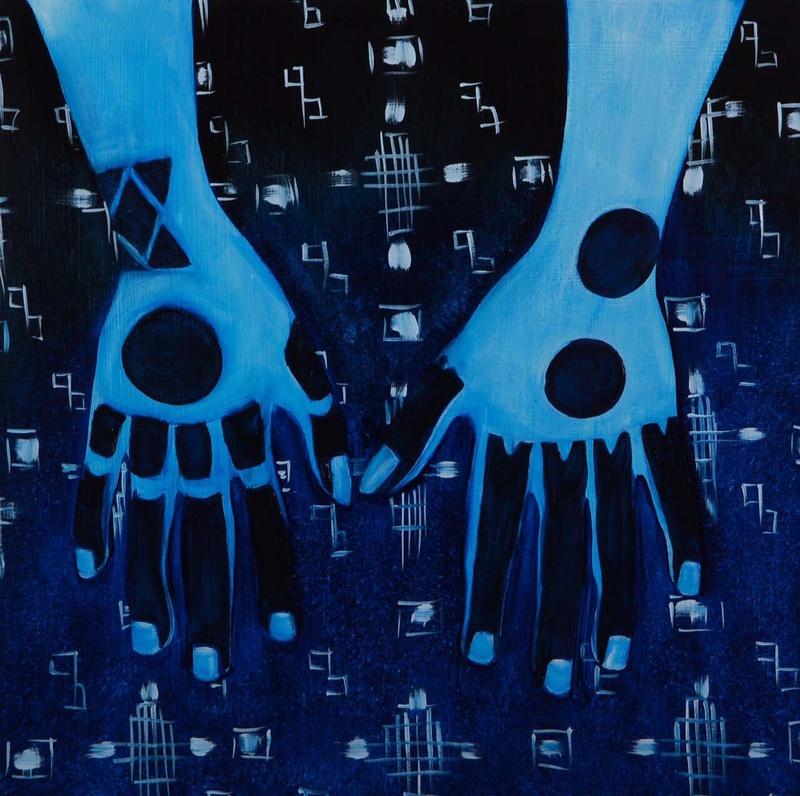

Through different approaches—painting and photography, respectively—Kina and Momohara explore aspects of Asian American history in Hawai‘i through imagery that is at times both beautiful and haunting. Kina’s paintings have a ghostly quality as they feature Japanese and Okinawan immigrant women working as sugar cane plantation field laborers. Momohara’s somewhat darkly toned photographic works depict settings and cultural items that serve as metaphors for immigrants’ life on Hawai‘i’s islands.

“Sugar/Islands began while I participating in the National Endowment for the Humanities Summer Institute, which was where I met Laura Kina for the first time,” Hauseur recalls. “Kina was already working on her Sugar project and was in communication with Emily Hanako Momohara, who also already began her Islands series. I had met Momohara in 2005 while on fellowship at the Smithsonian Institution through Roger Shimomura, a Sansei artist, about whom I was writing my master’s thesis.”

Hauseur credits Shimomura for introducing Momohara and Kina and spotting the parallels between their bodies of work. “The whole process of introduction to this show demonstrates that this incredibly vast world can at times be small,” says Hauseur.

She praises the artists’ work, which she says “must be seen in person to appreciate all the subtle details.”

The exhibition’s conception, Hauseur says, originated by comparing and analyzing the way that the artists present their subject matter, and their nuanced styles, which evoke melancholic feelings.

“Immediately, I saw an important historical discussion of women’s migrant labor,” Hauseur says. “And that grew into an exploration of the artist’s identity through a non-lineal, imperfect understanding of what comprises one’s history.”

Varying interpretations of history, Momohara notes, can be rich material for art. “For myself, truth is subjective. No one person has the same experience making the concrete impossible. In my work, I’m just as interested in the myths we create as I am the ‘facts.’”

Integral to those myths and histories in Momohara’s art are emotions that give them context and color. “Desire plays a large role. Desire to learn, desire to share and be known, desire to create a space for one’s self. With that comes mystery/discovery, myth/truth, and questions/answers. The Yin and the Yang describe one only existing with the friction of the opposite: Okinawa/Hawai‘i, Japan/America, History/Folklore, etc. Maria Seeda-Reeder wrote about my work in Aeqai saying that it was a ‘love song’ to my ancestors. Love and desire go hand in hand.”

Similarly, Kina concurs, explaining that illuminating the human aspects of Hawai‘i’s history is compelling to her as an artist. “I’m not interested in mere illustrations of history or telling people in a didactic way what my politics are. I want to reanimate the past, to feel it, so that it matters for our present moment.”

But while both artists are subtle in incorporating social issues into their art, the immigrant generation of their families remains a powerful influence. “The sociopolitical is at the heart of my work,” Kina says. “These are works about women’s history, about labor and migration, about World War II, about being Uchinanchu (part of the Okinawan diaspora), and about transnational connections between Hawai‘i and Okinawa. That content matters an awful lot to me.”

“I was fortunate to spend a significant amount of time with my great-grandmother, Hanako Doi,” says Momohara. “However, I was not old enough to think critically about her immigration to America. Although she definitely influenced my creative practice, she taught me how to mix cultures beautifully. Bachan’s Buddhist-style altar in homage to Jesus was the norm for me. In a way, my work is a mirror of her way of life. I look at the similarities and contrasts of mixed-race life and make imagery to address these ideas and emotions.”

“By looking at Kina’s and Momohara’s work, I want viewers to learn about women’s migrant laborer history from Okinawa to Hawai‘i, and the importance of your personal history, your ancestors’ journey, and how that has influenced who you are today,” says Hauseur. “I hope that there is not just a solo, contemplative engagement but multi-person, active dialogues that are generated from the show.”

Some of those dialogues have already begun, among audience members who have seen some of the works that will be incorporated into the exhibition. Ironically, Momohara has found that Americans sometimes are the ones who have the most difficulty recognizing the American influences in her work. “I think the most exciting reaction is from Japanese and Chinese nationals,” she says. “They understand how utterly un-Japanese my work is. This is something that is lost on American audiences. My faux constructions are seen as myths and personal interpretations of an American of Japanese descent. No matter how I struggle to learn and find myself in my ancestors, I grew up in America. Japan is foreign to me. It’s an additional layer that is really exciting [to] have explored with an audience.”

In considering the exhibition, Hauseur comments that she is always surprised by how much she regrets not pausing to spend more time to talk with her relatives to learn more about her own family’s past. “This is something I encourage all people to do with their parents, children, grandparents, and grandchildren, as your history is something sacred and unique to each individual.”

“Art is the best way to inspire learning,” Hauseur adds. “It encourages you to pose questions and problem solve through your over creative means. Beyond the historical significance, this show simply asks the audience to think about his/her ancestors and what makes you, you.”

* * * * *

Sugar/Islands: Finding Okinawa in Hawai‘i is on view from July 11 – September 6, 2015, at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

© 2015 Japanese American National Museum