Ozaki was born November 3, 1904 in Kochi-ken, Japan, and came to Hawaiˋi on April 24, 1917. Otokichi married Hawaiˋi-born Hideko Ozaki, and they had four children aged two to eight when World War II broke out. He was one of several hundred Japanese immigrants in the Territory of Hawaiˋi to be arrested, and then was sent to eight different internment camps. His book captures his and his family’s experiences through letters, poetry, and later radio broadcasts that he gave after World War II ended.

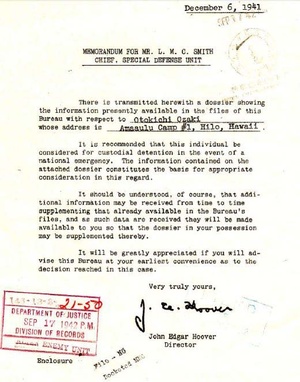

Even before Pearl Harbor, the FBI had compiled a dossier on Ozaki. He was under suspicion because he had formerly assisted the Japanese consul. People were being watched if they had even the smallest connections with the Japanese government. As a Japanese language teacher, Ozaki had been interviewed in April of 1941, where he told agent Dan M. Douglas that he was told by the president of the Hawaiˋian Japanese Central Educational Association that “due to the tense international situation it would be better if Japanese language school teachers were not consular agents to avoid suspicion.” Despite his best efforts, Ozaki was still under suspicion, as this letter (right) from J. Edgar Hoover notes. Note the date—the day before Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Ozaki was arrested on December 7, 1941, and sent to Kilauea Military Camp. His hearing before a board of officers and civilians appointed by the military governor on January 9, 1942 resulted in his being interned for the duration of the war because, the board said, 1) he was a subject of Japan and 2) he is loyal to Japan and that his activities have been pro-Japanese. The board further said, “after the cessation of hostilities we recommend that consideration be given to the subject of deportation of this individual. We do not see how this man can ever become loyal to the United States of America, and we do not believe that his children will ever be brought up as Americans.” In other words, deportation was recommended for someone not allowed by law to become a citizen because he and his children were not properly assimilating as Americans.

The board’s summary noted that he was a Japanese language school teacher and Consular Agent, whose duties consist of “assisting Japanese aliens and dual citizens, file certain notices with the Consulate and also gathering census data concerning Japanese residents and organizations in Hawaiˋi for the Consulate. Evidence to indicate these agents are under control of Consulate or that they are considered as ‘officials’ is very meager (emphasis added). Evidence shows OZAKI is pro-Japanese and has sent money to Japanese armed forces, but no evidence found that he is engaged in espionage, is a potential saboteur, or is disseminating subversive propaganda, except possibly by teaching school children under his direction the Japanese culture and loyalty to ancestral country.”

Ozaki’s file is full of reports from those saying he listened to radio broadcasts, confidential informants, interviews with his neighbors and others who had been watching him. In his testimony, Ozaki said that consular agents assisted Japanese to file notices with the Consulate of birth, death, marriage, registration for military service and others, all of which are required by law in Japan. The report noted, “Nothing was found to indicate he is engaged in espionage or is a potential saboteur, but possibly that he is engaged in verbal propaganda in a small way among his own race.”

Not until June 21, 1943 did the assistant attorney general note in a form letter in Ozaki’s file that consular agents engaged in functions commonly performed by a notary public and “the facts in this case are not sufficient to warrant prosecution particularly in view of the fact that the War Department opposed proceeding against so-called ‘consular agents’ and since the subject is now interned by the military authorities for the duration of the war.”

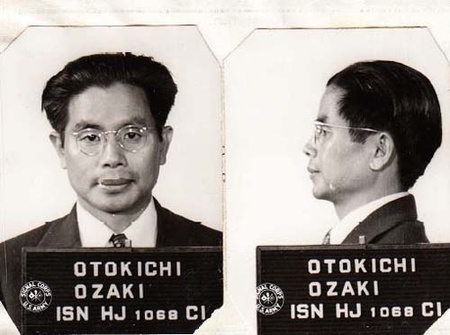

Ozaki left the Kilauea camp on February 19, 1942 and then was at the Honolulu Immigration Station for 11 days and then the Sand Island Detention Camp for 18 days, then was sent to the mainland. After eight days, he arrived at Angel Island. “In addition to the number ‘1068’ [given him in Hawaiˋi], I was assigned another number when we arrived at the Immigration Station on Angel Island in San Francisco. An eight-by-twelve inch denim ID tag with the number ‘346’ was pinned on the back of the collar of my coat. We were warned by the officer-in-charge that without these ID tags, we would not be allowed in the dining hall. For the first few days, it was odd to see these big tags on the backs of the internees. Although I could not see mine, I could clearly see the tag of someone in front of me.

“‘Hey, No. 287, you look good with your ID!’ We teased one another in this way.”

Ozaki was held on Angel Island from March 30 to about April 7, 1942. He described his arrival in an undated radio script. “When we reported to the [Angel Island] Immigration Station in San Francisco, soldiers ordered us to remove our clothing, searched our belongings, and took them all away. A week later, when we were about to be transferred and our belongings returned to us, three watches were found to be missing. All of them were expensive (more than $100) gold-plated watches. We had our representative file a complaint right away. We were asked, ‘Do you remember the faces of the soldiers who conducted the search?’ and ‘When did this take place?’ The result was that we were body-searched, then hustled out into the backyard while our government-issued duffle bags—our entire fortunes—were inspected. Even the mattresses on our beds were turned over in the thorough search for the watches.

“Our belongings had been taken away, yet we were treated as though we were the thieves. There was no reason at all for us to have been suspected of stealing. Things were going the wrong way. It should have been the other way around. Shocked by the turn of events, the owners of the watches bowed and apologized to the rest of us for the problem they had caused. For me the incident was more comical than infuriating. With tongue-in-cheek, I said to my friend Mr. K, ‘The watches probably turned into drinking money, and by now the thieving soldiers are having a good time. I’ve heard of Chinese soldiers stealing from prisoners, but I guess they’re not the only ones.’ In the end, the watches never turned up among our belongings (Honda, page 51).”

Ozaki also noted that many of their belongings were missing from suitcases they had checked in at the Kilauea Camp when they arrived at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. Despite submitting a 23-page list of his belongings valued at a few thousand dollars, he never received any compensation.

“The day came when we were taken by boat to an inland location, crossing San Francisco Bay and passing under the Oakland Bay Bridge. We disembarked at a pier with a sign that read, ‘Oakland.’ It was the night of April 6, 1942, when 167 of us boarded a Southern Pacific Line train that had been waiting for us. We had on the same shirts with our ID tag numbers pinned on our backs. On the afternoon of April 9, after traveling 2,000 miles, we reached a station in Lawton, near Fort Sill, Oklahoma. I wrote a poem at the time.”

Closer and closer

ID tag removed from my back

How light I feel! (Honda, p.47)

Ozaki describes his arrival at Fort Sill. After several hours waiting in the sun for his medical check, he went to a makeshift clinic, “where we were stripped naked. When told to hold out my chest, I thought I was to be inoculated. Instead, the number ‘111’ was written in red ink across my entire chest. An overwhelming sense of anger came over me. Large numerals written directly on my skin in red as though I am an animal—how can a civilized country like America do such a thing? It made me feel very sad.

“That night I took a shower and tried to scrub off the numbers with soap, but they did not come off easily. I still recall that one of my fellow internees complained about [the Americans’] uncivilized acts, saying they had treated us like cattle or horses.”

According to Honda, Ozaki spent 51 days at Fort Sill, and then was transferred to the Livingston Internment Camp in Louisiana from May 30, 1942 to June 2, 1943. Halfway through that stay in January of 1943, his wife Hideko and children arrived at the Jerome Incarceration Center in Arkansas, but Ozaki was not allowed to join them until over a year later; after Livingston, he was sent to the Santa Fe Internment Camp in New Mexico. He finally joined Hideko and his four children at Jerome in May of 1944, 28 months after he was taken away from them. Then they went together to the Tule Lake center near the California-Oregon border from May 1944 to December 2, 1945, and then finally allowed to go home and arrived in Honolulu on December 10, 1945, 1,460 days after Ozaki was arrested.

After release, Ozaki managed his father-in-law’s Blue Ocean Inn before working for the Hawaiˋi Times newspaper from 1947 to 1977. He wrote under his pen name, Muin Ozaki and joined the Cho-on Shisha (Sound of the Sea) tanka club and helped edit two tanka anthologies. He also appeared on several radio stations on Oˋahu, from whose scripts the accounts in this story are taken. In the late 1970s he received the Sixth Class Order of the Sacred Treasure from the emperor of Japan. Ozaki died on December 3, 1983 at the age of seventy-nine (Honda, page 244).

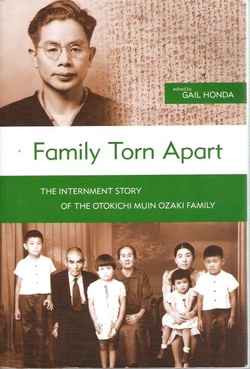

Family Torn Apart allows the reader to experience Ozaki’s ordeal as he travels about very hot and very cold, desolate areas of the United States, waiting to be reunited with his family and dealing with bureaucracy and apathy about his situation. Angel Island was one of many stops during his four-year ordeal.

Resources

Honda, Gail (ed.). Family Torn Apart. Honolulu, Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiˋi, 2012.

National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD. Record Groups 60 and 389. Special thanks to researchers Adriana Marroquin and Gem Daus for their assistance in accessing these records.

For more information on Family Torn Apart, visit the website of the Japanese Cultural Center of Hawaiˋi.

*This article was originally published by the Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation.

© 2015 Angel Island Immigration Station Foundation