I spent my childhood years during the 1950s in the San Fernando Valley. My parents, like a number of other Nikkei families, were flower growers and we had a farm on which we grew carnations, chrysanthemums, anemones, asters, and other flowers. During the summers, I spent many hours working under the hot Valley sun, and I always became dark and tanned, just like my parents, my brothers, and all the hired help we had on the farm.

The elementary schools I attended were a mixture of predominantly white kids with a strong Hispanic representation. In 1955, I started attending Northridge Junior High School and found myself one of only three non-whites in the entire school—the other being Japanese Americans—one of whom was the student body president. This school was absolutely WHITE—there weren’t even any Italians. Everyone was a non-Hispanic Caucasian, and many were Jewish. I actually had a great time during my year there; I was treated like a foreign-exchange student and most of the people on campus wanted to know me because I was “different,” and I admit it—it was nice to be treated as someone a little “special.” On the down side, however, I also knew I wasn’t “one of them,” and I was self-conscious about my being different, each day, every day, all day.

After one year at Northridge Junior, I transferred to Pacoima Junior High, which was, at the time, the only racially integrated middle school in the Valley. We had Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, and Asians (by Asian, I mean mostly Japanese Americans, which numbered about 30 kids; there were only a very few Chinese and Pilipinos in the Valley at that time). I was so racially naïve that I knew that Pacoima was different from Northridge, but it didn’t dawn on me how and why it was different. Even though the racial complexion of the students between the two schools was such a contrast, I was barely aware of it, and had no sense why it was so. To my 12-year-old brain, kids were kids, and you just tried to make do the best you could and get through each day. I was no longer seen as “special” but that was OK. I was one of the mixture, and I didn’t feel quite so “different” from everyone else.

This was my growing up—being a Japanese American kid in a predominantly non-Japanese American world. There were no minorities to be seen in positive role images, either in the movies or on television. Back then, in the ’50s, there was seemingly little about our ethnicity that Japanese or JAs had to be proud about. My parents instilled a general sense of self-esteem in me by telling me that Japanese people were the best and smartest people in the world. This ethnocentric view was somewhat validated because many of the school leaders were JA (like Northridge Junior High). But this was esteem by association rather than any real self-esteem (and when I got to college and then met some Jewish kids who were REALLY smart, I realized Japanese were not the smartest in the world).

One semester, during my high school chemistry class, I sat next to a vivacious and pretty Caucasian girl named Melodee Weaver. She sat next to me in several classes because we were both “Ws” and many teachers assigned seats alphabetically. She was very nice and was one of the few white girls who was friendly to me; in fact, I think she was one of the few white friends I had in high school (although I had many white acquaintances, they weren’t necessarily friends). During one class experiment where Melodee and I were lab partners, she happened to place her hand on my bare arm. I was startled to see how white her hand looked against the dark tanned skin of my arm. I immediately tried to nonchalantly pull my arm away before she saw what I saw because I was afraid she would not want to touch me, since I was so dark. Her touch didn’t seem to bother her in the least, but it bothered me, and it bothered me that it bothered me. Why did I feel she would not want to touch me? Why was I ashamed of my darkness? I thought about these feelings, but didn’t have any answers for a long time.

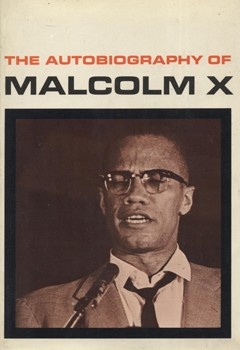

I graduated from high school in 1961, and in 1965, during my senior year in college, I read The Autography of Malcolm X by Alex Haley. This book was a turning point in my life. Other than the Bible, no other book has so significantly affected the way I saw the world and myself. Malcolm X described racism in America in point-blank terms. His honesty and personal experiences put you at one with him, and his analysis of social forces was so clear and explicit that aspects and experiences of your own world just became sharper and clearer. In one section of his book, he describes how, as a young man, he was caught up in the desire to look more “white” and would, like many other black men, undergo a terribly painful process in order to take the curls out of his hair and make it straight. It was a form of self-hate and self-denial, and I could, in my own way, relate to his experience.

I began to understand why I tried to pull away from Melodee’s touch, and why I was ashamed of my dark skin. My eyes became opened to the broad impacts of institutional racism, and how we have to counteract those false notions of inferiority with the greater sense of the common value we all have as human beings. Even though Malcolm was a devout Muslim and I a devout Christian, Malcolm’s story helped me start a life-long journey of trying to overcome racism in myself and in society, and to accept the notion that I could do something of value to help make the world a better place.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices: Turning Points, in January 2002. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2002 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California