Mexico is the second most popular destination for students and working adults interested in Spanish-speaking countries for study abroad or training, after Spain. It is well known for its cheerful and bright national character, richly flavored cuisine, and tequila (a distilled liquor with an alcohol content of 45 to 50%), and attracts many Japanese people. Some of my students have traveled there during summer vacation, and some have even found employment at Japanese companies there after graduation.

Economically, the country is located in North America, but as a Spanish-speaking country, it is also a member of Latin America culturally and socially, and is a great economic power. Its gross domestic product is $1.2 trillion (equivalent to 140 trillion yen when converted at 120 yen to the dollar), and its average income per capita is over $10,000 (equivalent to 1.2 million yen). Like other emerging countries, its growth rate is currently slowing, but its unemployment rate is low at less than 5%. Although its trade balance is slightly in deficit, exports and imports are almost the same amount at $380 billion (equivalent to 43 trillion yen), and in recent years, exports related to automobiles have grown dramatically. Although oil is the main export, exports of industrial products exceed 30% of the total in value terms. Exports of electrical and electronic parts are also doing well. However, it is characterized by the fact that 80% of exports go to the American market. In order to maintain these export industries, it does not produce much domestically and imports a large amount of raw materials from Asian countries. In particular, the procurement ratio from China, Japan, and Korea is high.

Mexico is also a participant in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, and is also a founding member of the Pacific Alliance (a relatively flexible free trade agreement consisting of Chile, Colombia, Peru, and Mexico), which is currently attracting a lot of attention. Japan is also very interested in these efforts, and a bilateral economic partnership agreement (EPA) has already been concluded (effective since April 2005). As a result, there are currently 630 Japanese companies operating in the country, with approximately 10,000 Japanese people involved in business activities (these figures are all from 2013, but the number of companies operating in the country has increased further in the past year or so).

Many major automobile manufacturers (Toyota, Nissan, Mazda, Honda) and the parts manufacturers and logistics service companies that support them have also expanded into Mexico, and recently they have been concentrating in the central Mexican states of Guanajuato and Queretaro. When I visited Guadalajara last October, the shortage of interpreters, bilingual office staff, and engineers in this industry was a hot topic. In recent years, both Western and Japanese companies have focused on not only small and medium-sized sedans and trucks that can be manufactured with cheap labor, but also on high-profit luxury cars. To achieve this, securing skilled labor in various specialized fields is a bottleneck. The scramble for human resources between foreign companies has been pointed out for some time, but the number of experienced and specialized personnel is limited, and the shortage of technical personnel is a major concern not only in Mexico but throughout Latin America.

Japan imports not only tequila from Mexico, but also avocados, asparagus, mangoes, melons, limes, pumpkins, bluefin tuna, and other products that are commonly seen in Japanese supermarkets, and in recent years, beef has also been imported along with pork and beef tongue.

And in contrast to this vibrant economic activity, there is growing concern over the frequent occurrence of murders due to fighting between drug cartels and criminal organizations, and the deterioration of public safety in some areas. Ten days before I arrived in Guadalajara, a tragic incident occurred in Iguala city, Guerrero state, where 43 students from an agricultural normal school were attacked by police and drug cartels while traveling by bus, and the students are still missing.

Furthermore, the existence of "transit migrants" coming from Central American countries and northern South America on the way to the United States has also become prey to these criminal organizations, and the enslavement of minors, violence against young girls, and forced prostitution have become international problems. The security authorities are also divided into several jurisdictions, and insufficient cooperation and corruption in politics and administration have led to many cases going unsolved, making it difficult to distinguish between ordinary crime and organized crime.

It is also one of the most unequal societies along with Brazil, and there is strong criticism that wealth is more concentrated than ever before in the hands of a select few individuals and business groups. Although Mexico is a country that can play a leading role among emerging nations, there is no end to the number of people immigrating to the United States, both legal and illegal. In fact, 10% of the total population of 300 million in the United States are Mexican immigrants (many of whom have already acquired American citizenship), making up 67% of the Hispanic group and a quarter of the Mexicans scattered around the world. Illegal Mexican immigration to the United States seems to have decreased somewhat in recent years, but illegal immigration from other Central American countries is still on the rise.

In October 2014, I visited Mexico at the invitation of the University of Guadalajara in central Mexico, where I met with researchers and graduate students involved in immigration and social issues and gave two special lectures on "Japan's social integration policy for immigrants and the settlement situation and challenges of South American residents."

Many Mexicans have emigrated overseas, and their presence in the neighboring United States, in particular, is indispensable in the agricultural, service and processing industries, and from the second generation onwards, they have come to have a great influence on government and politics. On the other hand, as a result of close economic ties, for example, there is an American retirement village near Lake Chapala, 40 km northeast of Guadalajara, where many large and small mansions and condominiums have been built, and restaurants, hotels, mobile phone companies, etc. almost all speak English. It seems that it was a villa area for the upper class of Guadalajara a long time ago, but now tens of thousands of Americans live there, and many of them seem to spend most of the year there. It is very convenient, as it is only three hours away from Los Angeles, and there are daily flights to other major cities such as Houston, Atlanta, Dallas and New York. According to the 2010 Mexican census, Americans form the largest community, with nearly 770,000 people, accounting for 75% of the foreign population.

Migration from Mexico to the United States is not limited to farmers and indigenous people who cannot find work, but also includes many young people in urban areas who have not completed secondary education and university graduates. However, including people from other Central American countries, more than one million people attempt to cross the border illegally each year (about 20% of them are arrested at the border and forcibly returned to their countries of origin). However, over their long history, Mexicans have now become a huge minority, numbering 30 million. On the other hand, Mexico has also accepted many refugees from Spain during the Franco era, Cuba under Castro, and military regimes in South American countries, so Spaniards are the second largest group, at about 80,000, followed by Cubans, Argentines, Colombians, etc., each with around 12,000 people.

A few years ago, a law change created a "transit visa" for those from Central American countries who wish to migrate to the United States, but in reality, most of them are unable to meet the conditions required by the law, such as a contract that guarantees work in the United States and funds to cover the cost of living in Mexico. As a result, hundreds of thousands of Central Americans, including minors, enter the country illegally every year as refugees. As a result, they have become prey to criminal organizations and security in various parts of Mexico has worsened. The United States is asking Mexico to strengthen the management of foreigners' stays, but Mexico is asking other Central American countries to implement stricter immigration management. It is not easy for either country to manage the vast border area (more than 3,000 km to the north with the United States and just under 1,000 km to the south with Guatemala), and the current situation is that even with stricter legal regulations, not much has been achieved.

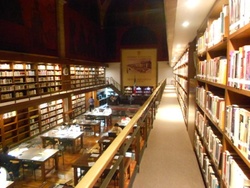

According to the opinions exchanged during this academic exchange, there are many research reports on Mexican migration to the United States. However, even if they are Mexican, the migration process varies considerably depending on factors such as which region or village they come from, whether they are indigenous or from an urban area, whether they are male or female, their educational level, and age, and university libraries and publishing companies have a wealth of specialized literature. However, the problem of Central American migrants illegally passing through Mexico, which has arisen over the past 10 years or so, has become quite mafia-like, so it is not so easy to investigate. There are some statistics and surveys by Catholic Church organizations and NGOs that support these foreigners, but it seems difficult to grasp the actual situation and improve it. There were many points made that the development of laws and the government's response have been delayed, and that the mere strengthening of police and border patrols has only partially solved the problem and is now ineffective.

I also spoke to a South American student at the University of Guadalajara, who said that it has become much tougher to obtain and renew a visa, and that driving without a license or participating in a minor protest can lead to immediate deportation. Many South American students hope to study at prestigious universities in Mexico (UNAM - National Autonomous University of Mexico, Colegio de México - Mexican Graduate School, etc.), so if a scholarship student causes a scandal, the sanctions are severe.

In any case, the current issue is that foreigners, mainly from the Caribbean (Haiti, Dominican Republic, etc.) and Central American countries (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, etc.), are illegally entering Mexico on the way to the United States and then trying to pass 2,500 kilometers from north to south, but it is extremely difficult to control a territory of 2 million square kilometers, seven times the size of Japan. Effective cooperation between multiple countries is necessary, but the systems of these countries are inadequate, and the economic imbalances and social disparities within each country are so serious that it is not easy to implement effective measures.

As for the social integration of foreigners, Japan does not have an immigration law, as foreign residents account for about 1% of the total population of 120 million. Therefore, there are no special policies or measures other than the immigration law that regulates residence status. However, when I explained the contents of various programs to support foreigners to settle down at home, run by the national, prefectural and municipal governments, the researchers were quite surprised. In Mexico, the majority of Americans are retired, so they have relatively high incomes and enjoy the rest of their lives in residential areas such as Lake Chapala, Guanajuato and San Miguel de Allende (there are more than 200,000 Americans in these retirement resorts). They are a group that does not need much support from the local government. Most of the rest are Spanish-speaking, so as long as they follow the customs and minimum rules of life, there are not many problems, they were pointed out.

Reference sites:

http://www.jetro.go.jp/world/cs_america/mx/

http://jp.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303529604579094044237202888

http://www.newsweekjapan.jp/reizei/2014/07/post-663_1.php

© 2015 Alberto J. Matsumoto